The Little College Where Tuition Is Free and Every Student Is Given a Job

There’s a small burst of air that explodes from every clap. And when hundreds of people are clapping in unison, it begins to feel like a breeze—one that was pulsing through the Phelps Stokes Chapel at Berea College in Kentucky. The students and staff that had gathered here were stomping, clapping, and singing along, as they were led in a rendition of the Civil Rights era anthem, “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around.”

They had packed into the wood-framed building for a convocation address, where the speaker, Diane White-Clayton, would be talking about “Jesus, the Ultimate Rebel with a Cause.” Berea does not have a sectarian affiliation, but the remnants of its Christian foundation are readily apparent—so much so that, as Alicestyne Turley, a history professor at the college, told me, “we have students who come here who think they’re coming to a Christian college,” à la Liberty University or Notre Dame.

White’s address was dotted with the markings of a Sunday sermon—not the stuffy kind, but the kind I’d heard time and again growing up—the jokes, the whooping, the lessons that come in threes. In her speech, White explained to the students that it didn’t take supernatural abilities to do great things—only a purpose—and that all the evidence they needed could be found on the campus where they stood.

Berea College isn’t like most other colleges. It was founded in 1855 by a Presbyterian minister who was an abolitionist. It was the first integrated, co-educational college in the South. And it has not charged students tuition since 1892. Every student on campus works, and its labor program is like work-study on steroids. The work includes everyday tasks such as janitorial services, but older students are often assigned jobs aligned to their academic program, and work on things such as web production or managing volunteer programs. And students receive a physical check for their labor that can go toward housing and living expenses. Forty-five percent of graduates have no debt, and the ones who do have an average of less than $7,000 in debt, according to Luke Hodson, the college’s director of admissions.

On top of all of that: More than 90 percent of Berea College students are eligible to receive the Pell Grant—often used as a proxy for low-income enrollment. Most of those students, 70 percent to be exact, are from Appalachia—where nearly one of every five people live below the poverty line. And that recruiting pipeline in Appalachia produces a rather diverse class—more than 40 percent of the student body identify as racial minorities.

Every couple of years, Berea College makes national news, often for its tuition-free promise—a promise that has become all the more noteworthy as the national student debt crisis has grown. But late last year, Berea College made headlines for a different reason: a provision in the Republican-led tax reform effort that would have charged colleges with large endowments a 1.4 percent tax on the investment earnings from their endowments.

Berea has a $1.2 billion endowment—which is how it can afford to cover the tuition of every student—and the school estimated that the tax would cost it upwards of a million dollars a year, effectively forcing it to cut back on the number of students admitted. The rebuke came quickly from both sides of the aisle. Democrats argued that it was an example of Republican mismanagement of the entire tax debate, and Republicans painted the debacle as Democrats holding a worthy college hostage. It was a point of order raised by Senator Bernie Sanders, Republicans argued, that prevented Berea from being exempt from the tax in the initial bill. Higher education leaders—even notable Republicans such as the Bush-era education secretary Margaret Spellings—were skeptical of the tax. The tax’s goal was ostensibly to punish colleges for amassing large endowments as the cost of college was rising, and not evenly helping students. By ensnaring Berea, a college that charged no tuition because it has such a large endowment, the logic of the tax broke down.

Ultimately, through a mix of righteous indignation and friends in high places, including Kentucky Senator Mitch McConnell, language was added to the bill saying that a school needs to have 500 “tuition-paying” students to qualify for the tax. That exempted Berea, where no students pay tuition. But the dust-up did raise an interesting question. If Berea can do so much with a $1.2 billion endowment, why can’t the Harvards of the world do the same with their billion-dollar endowments? The answer lies in Berea’s unique history.

erea college had been around for less than a decade when its founder was run out of town.

John G. Fee, a minister and abolitionist, opened Berea in 1855 on land provided by Cassius Clay—the son of Kentucky’s largest slaveholder—who also happened to be an abolitionist, though one who favored gradual emancipation. The school has a simple motto: “God has made of one blood all the peoples of the earth.” The education of those people, Fee believed, should reflect that.

Needless to say, Fee’s belief in interracial education rubbed the slaveholders in Kentucky the wrong way. In 1859, national tensions over the direction of the country—whether slavery was the future or not—began to boil over. More than 60 armed white men attacked Berea, telling the abolitionist families that they had 10 days to leave the state, or they would be killed. Fee and his family—ardent abolitionists themselves—were among those who left.

So, with his family, Fee fled to Ohio, and the college was forced to cease operation. The winter weather made for a difficult exodus, and his youngest son died from diphtheria. The family carried the young boy’s body back to Kentucky where he was buried. Fee would later write that the ordeal strengthened his, “purpose to return, and my claim upon this, my native soil and field of labor.” But perhaps it strengthened his wife Matilda’s resolve more. During the Civil War, Matilda returned to Berea. John, not to be left behind, followed at the war’s end.

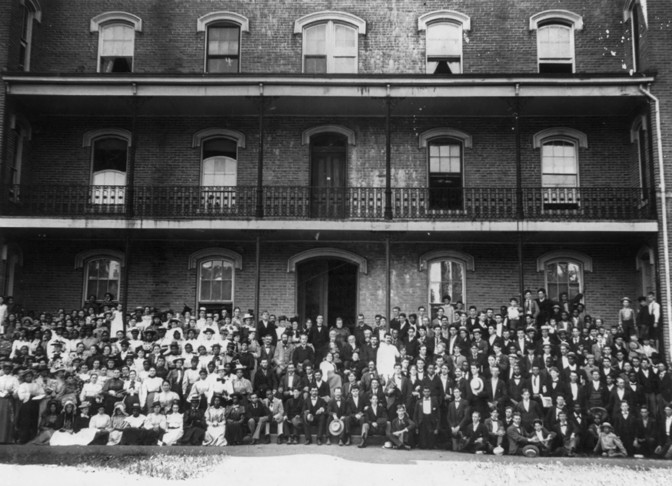

But Fee didn’t come back to Berea alone. He had been devoting the lion’s share of his time to educating—and preaching to—recently freed black people at Camp Nelson, in Kentucky, near the end of the war. He brought dozens of those people with him to reopen Berea College after the war. In the late 1800s, the student body was roughly half white and half black. In 1889, for example, there were 177 black students and 157 white. And all of the students worked on the campus grounds. That had been a central tenet of the college from the beginning. Work, Fee believed, was the great equalizer.

As the school grew, it officially became tuition-free. A new president, William Frost, whose family housed enslaved people who fled captivity during the war, published an advertisement toward the end of the 19th century boasting that the college had “29 teachers and 12 buildings,” that it was endorsed by “Christian Bodies of every name,” and, most importantly, that “Tuition is Free!”

The ad undoubtedly caught the eye of several students, including, potentially, Carter G. Woodson, a plucky young black man who enrolled at Berea in 1897, and a historian who would go on to be known as the “father of black history.” But at the same time, Berea’s interracial education made a lot of Kentuckians uncomfortable. Most notable was Carl Day, a Kentucky legislator, who, lore has it, was taking a train through Berea when he saw two young women—one white, one black—embracing each other. Day introduced a bill in the Kentucky House of Representatives on January 12, 1904, that would prohibit white students from attending school with black students. Schools found to be in violation of that law would be forced to pay a $1,000 fine for each day they were in violation of the law — and teachers could be fined $100 a day. Berea was the only integrated college in Kentucky at the time.

The Day Law, as it came to be known, was passed in 1904, and the college tried to find a way around it. It considered opening an auxiliary campus, but the law expressly prohibited colleges from operating an integrated campus within 25 miles of their main campuses. They sued, but Kentucky’s high court agreed that the law was necessary to prevent interracial marriage and racial violence. And the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the state’s ruling, citing its decision in Plessy v. Ferguson that it was within a state’s rights to prohibit integration. Only one Supreme Court justice dissented: John Marshall Harlan, a native Kentuckian, who had also dissented in the Plessy case. “Have we become so inoculated with prejudice of race,” Harlan wrote in his dissent, “that an American Government, professedly based on the principles of freedom, and charged with the protection of all citizens alike, can make distinctions between such citizens in the matter of their voluntary meeting for innocent purposes simply because of their respective races?” Loretta Reynolds, dean of the chapel at Berea, perhaps put it best: “It was a sinister law.”

After the Day Law took effect, the college paid for the black students who had been enrolled but had not completed their degree programs to attend historically black colleges and universities. And it split its endowment to open the Lincoln Institute for black students in Simpsonville, Kentucky. But little by little, year by year, students, faculty, and staff began to forget the institution’s history and commitment to interracial education. In some ways, that forgetting was intentional. The college was struggling financially—most of its money had dried up—and it needed to find something that people would support, Turley told me, “and what people would support was the education of poor whites.”

The prospect of educating poor white people from Appalachia for no tuition was something that the community could get behind. And nearly 100 years ago, on October 20, 1920, the board made sure that the college would be able to do so for a long time. According to Jeff Amburgey, the school’s chief financial officer, “The board essentially said, for Berea to sustain its funding model,” any unrestricted bequests—essentially money that someone leaves the institution after they have passed away, that is not tagged for a specific purpose—could not be spent right away. Instead, he says, the money was expected to be treated as part of the endowment, and only the return on that investment could be spent.

The college has followed that policy ever since. In fact, as Amburgey told me, “46 percent of our endowment, as of June 30, 2018, is what we call quasi-endowment, so, roughly $500 million is the current market value of those unrestricted bequests” since 1920.

But as the college was rebuilding its finances, there were no black students. Between 1904 and 1950, the Day Law prohibited black students from attending the college. In 1950, however, the law was amended to allow voluntary integration above the high school level. Two black students, William Ballew and Elizabeth Denney, enrolled that year. And in 1954, the year the Supreme Court ruled segregated schools unconstitutional in Brown v. Board, Jessie Zander became the first black graduate of the college since the Day Law took effect.

The reintegration of the campus was difficult. “The community was gone,” Turley told me. There were still the black people who worked for the school, and lived in the community, but the community of students and faculty had been decimated by the law. The school had to relearn the philosophy of its founder, John Fee, slowly, but surely. Six or seven black students came back in the ’50s. A few more in the ’60s. And, by the ’70s, black students made up roughly 6 percent of the student population.

Each year, the school has built on those numbers, and now black students make up 27 percent, Latino students 11 percent, and international students—who are required to be low-income by the standards of their own countries—make up another 7 percent. Several people who I spoke with lamented that the numbers sound good, but they’re nowhere close to the 50-50 enrollment Berea once had. However, they’re doing far better than a lot of similarly situated liberal-arts institutions. And it’s tuition-free—something that states are struggling to achieve for their public colleges. It seems like as close to an ideal system for low-income higher education as is possible, but school officials worry it may not last forever.

eff amburgey spends a lot of time thinking about the worst-case scenario. The endowment is what keeps the lights on—literally. About 75 percent of Berea’s operating budget comes from endowment investment earnings—the spendable return on the endowment. Another 10 percent of the budget is from charitable giving, another 10 percent is from federal and state grants such as Pell, and then there is other, extraneous income making up the other five percent. The school pays the tuition, $39,400 per student a year, internally.

But having an endowment pay for most of a college’s expenses rather than, say, tuition, can be a recipe for gambler’s ruin. As Lyle Roelofs, Berea’s president, told me, “we’re not the kind of institution that holds the world of finance in disdain. We are dependent on it.” If the stock market were to dip—lowering the endowment’s return on investment—the college might have to reconsider its tuition promise.

The college has been tested before. In the 1970s, Willis Weatherford Jr., the president at the time, broached the idea of charging tuition as the financial markets went sideways during Vietnam. But the college started accepting federal funds instead—things such as Pell Grants. Following September 11th, the prospect of charging tuition was raised again, and again in 2008 to 2009 when the recession hit. Every time they decided against it. Each of these financial downturns hit the school hard, says Amburgey, but they aren’t close to the the worst of the possibilities he’s considered.

The worst thing that could happen to Berea, Amburgey says, would be a financial market that went down—triggering less than 5 percent returns on their endowment each year (roughly the amount they spend each year to keep the place running)—and stayed that way for a long time. Imagine the worst part of the 2009 financial crisis lasting for a decade. The college has mechanisms built in to help sustain it in such an event. In the 1990s, for example, when the college had a 39 percent return on its investment one year, they stashed money away in a sort of rainy-day fund. But rainy-day funds are useless in a flood.

Berea’s system seems like a solution for the ballooning prices that plague students at many U.S. colleges, but it’s also something that would be incredibly hard to replicate for most institutions. Berea has been building this model for more than a century—if another college were to switch to this model without an existing financial cushion, a recession could essentially close their institution.

But it’s possible colleges could start by emulating certain elements of the Berea model. Paul Quinn College, a historically black college in Dallas, recently started employing its students on campus, and joined the work-college consortium, a group of federally designated work colleges, in 2017. The institution, which once feared closure, has now announced the opening of a second campus.

But going tuition-free is a bigger ask. Berea College enrolls between 1,600 and 1,700 students in any given year, so scaling a tuition promise like theirs would be a much heavier lift for public regional colleges, and even larger private colleges. It would be theoretically doable, though, for some highly selective colleges with massive endowments. Some of them, such as Princeton, Brown, and Cornell, have already eliminated tuition for low-income students. But endowments are not like bank accounts where all of, say, Harvard’s $37 billion can accessed instantly—often some of those funds are earmarked for specific things such as a professorship, or a program, or a specific scholarship. Colleges can not legally break that agreement.

Berea largely owes its success today to the board’s decision, roughly 100 years ago, to make sure there would be endowment funds to spend on students. And to the decades of leaders since who have kept that commitment.

The energy that pulsed through the wooden risers in the Phelps Stokes Chapel was palpable as the students sang. “Just march,” Diane White-Clayton told them, “because some of y’all aren’t singing.” The students laughed, as they stopped singing and clapping and simply stomped. “I want you all to leave here with the determination that nothing,” she exclaimed, “is going to turn you around!”

Higher education in America is plagued by many problems: limited access for low-income and minority students, affordability, etc.—but Berea is different than much of the rest of higher education. But those differences make it fragile. It’s unclear if its model will last forever, but for now, it has a simple purpose. It wants to keep education tuition-free for its students for as long as possible.

“Alright, give me back that bass line,” Clayton told them as the students began clapping again.

“I’m gonna keep on walkin’,” they bellowed, “keep on talkin’. Marching to my destiny.”

[Read more at The Atlantic]