Aldeman: Why Aren’t College Grads Becoming Teachers? The Answer Seems to Be Economic — and the Labor Market May Be Starting to Improve

Updated April 2

For several years, the education world has been worried about the decline in the number of students interested in becoming a teacher. In the wake of the Great Recession, the number of students pursuing education degrees and earning their teaching licenses began to plummet, and the declines were particularly severe in certain states.

But was this crisis mainly due to policy decisions in the education sector, or more a function of underlying economic conditions? I’ve long been on team economics. In support, I’ve pointed to a 2015 study showing that college students made their decisions about what major to pursue based on prevailing economic conditions. In fact, that study found that the number of students pursuing education degrees was more susceptible to labor market trends than any other field of study. When recessions have hit the American economy over the past 50 years, both men and women were less likely to want to become teachers and instead turned to fields like accounting and engineering.

The economy has improved markedly over the past few years, so according to the economic explanation, we should start to see more young people pursuing a teaching career. Is that happening?

My tentative answer is yes. We’re starting to see preliminary signs that the supply of new teachers is beginning to grow again. According to a reportissued in April, California has seen four consecutive years of increases for initial teaching credentials. And, while it made national headlines when Teach for America, the country’s largest provider of new educators, saw its applicant pool fall significantly from 2013-16, its subsequent rebound has happened much more quietly.

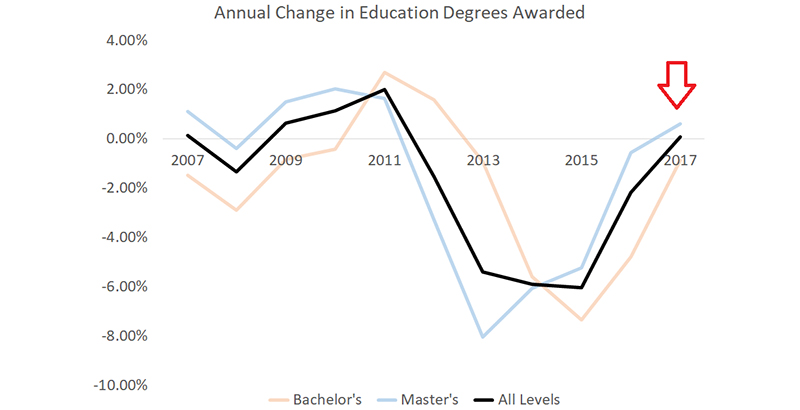

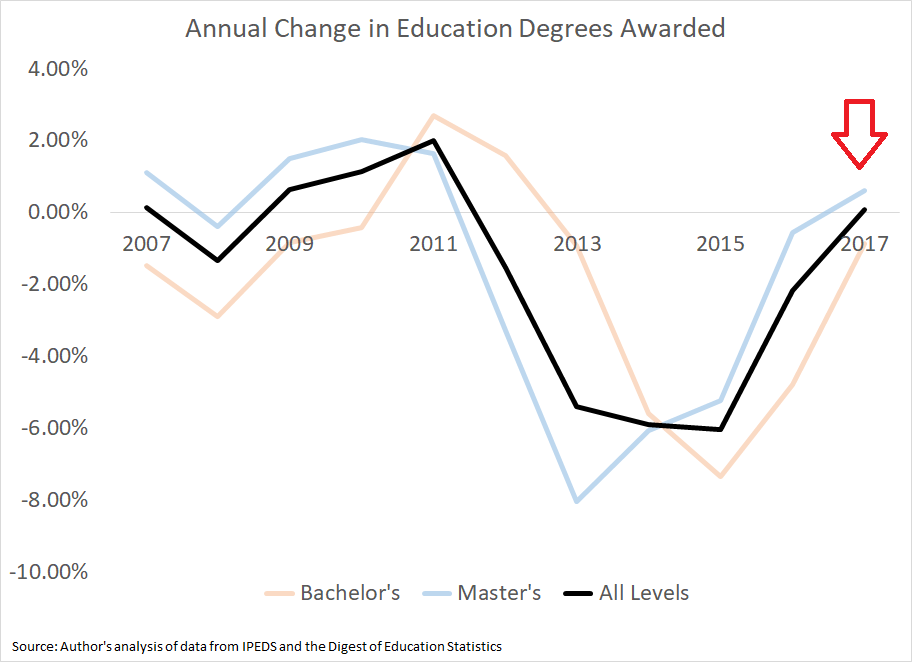

National data are starting to confirm these anecdotes. The most recent national statistics we have on new teacher licensures come from 2015-16, but we now have provisional data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System on college completions for the 2016-17 school year. Those numbers show a promising trend. After bottoming out in 2013, the year-over-year changes in the number of students completing an education degree got smaller and smaller. And in 2017, the most recent year for which we have data, we had the first year-over-year increase in college graduates with education degrees since 2012. It’s still not much — 2017 was just .62 percent higher than 2016 — but it could be the start of a promising trend.

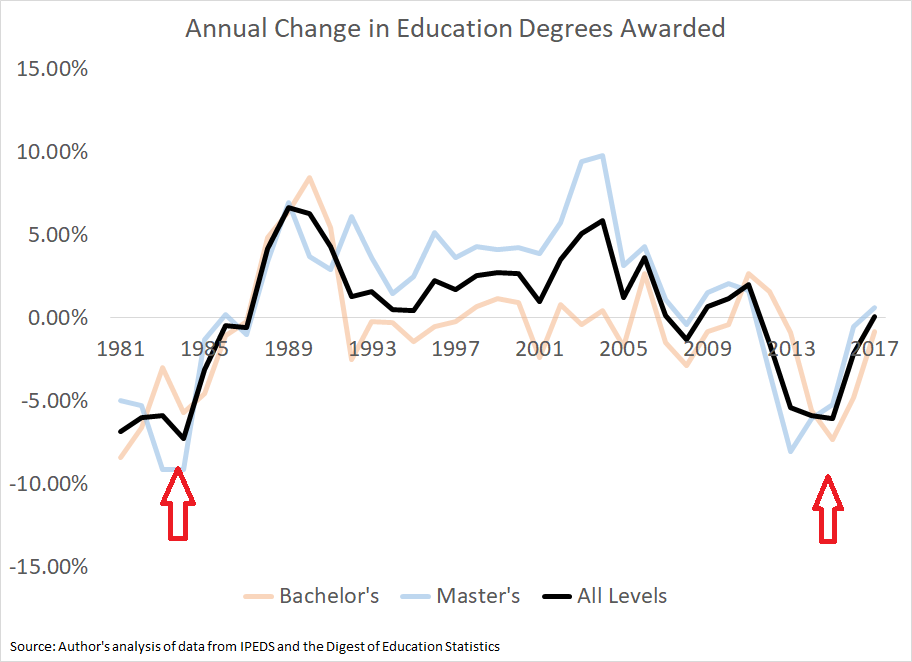

It has been a while, but this story has played out in American schools before. In the early 1980s, the number of young people graduating with education degrees was declining by 5 to 9 percent year-over-year. But things started to look less bad by 1986, and then we had 20 straight years of gains from 1988 through 2007.

These trends also match up with survey results about whether parents would want their children to become teachers. Just like the number of education degrees, answers to that question bottomed out in the early 1980s, rebounded in the late 1980s and remained high throughout most of the 1990s and early 2000s. Although those survey results hit a new low last year, the increase in the number of college students pursuing education degrees may portend another rise in the perceptions of parents.

Now, I’m not saying we’re likely to see the same stretch of gains in terms of perceptions or results we saw in the 1990s and early 2000s. That would depend on lots of other factors, including the number of college-age students and future economic conditions.

Nor am I saying the teacher labor market is perfectly balanced today. Even if the supply of new teacher candidates is starting to improve, it still may not match the growing demand for new educators. And as Kaitlin Pennington McVey and Justin Trinidad noted in a report for Bellwether Education Partners in January, some subject areas are chronically short of high-quality teacher candidates regardless of the underlying market conditions.

But these green shoots are an early indication that the teacher labor market may be starting to thaw. We’ll have to wait for more data to confirm these preliminary findings, but there’s reason to be hopeful that we’re on a positive trajectory.

[Read more at The 74]