Aldeman: Why Aren’t College Grads Becoming Teachers? The Answer Seems to Be Economic — and the Labor Market May Be Starting to Improve

Updated April 2

For several years, the education world has been worried about the decline in the number of students interested in becoming a teacher. In the wake of the Great Recession, the number of students pursuing education degrees and earning their teaching licenses began to plummet, and the declines were particularly severe in certain states.

But was this crisis mainly due to policy decisions in the education sector, or more a function of underlying economic conditions? I’ve long been on team economics. In support, I’ve pointed to a 2015 study showing that college students made their decisions about what major to pursue based on prevailing economic conditions. In fact, that study found that the number of students pursuing education degrees was more susceptible to labor market trends than any other field of study. When recessions have hit the American economy over the past 50 years, both men and women were less likely to want to become teachers and instead turned to fields like accounting and engineering.

The economy has improved markedly over the past few years, so according to the economic explanation, we should start to see more young people pursuing a teaching career. Is that happening?

My tentative answer is yes. We’re starting to see preliminary signs that the supply of new teachers is beginning to grow again. According to a reportissued in April, California has seen four consecutive years of increases for initial teaching credentials. And, while it made national headlines when Teach for America, the country’s largest provider of new educators, saw its applicant pool fall significantly from 2013-16, its subsequent rebound has happened much more quietly.

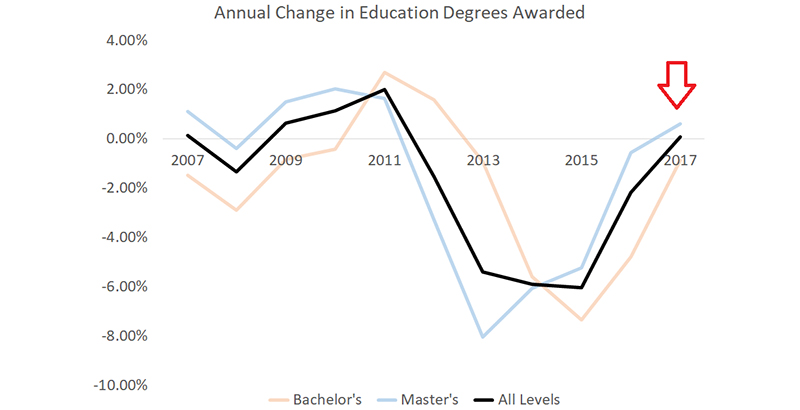

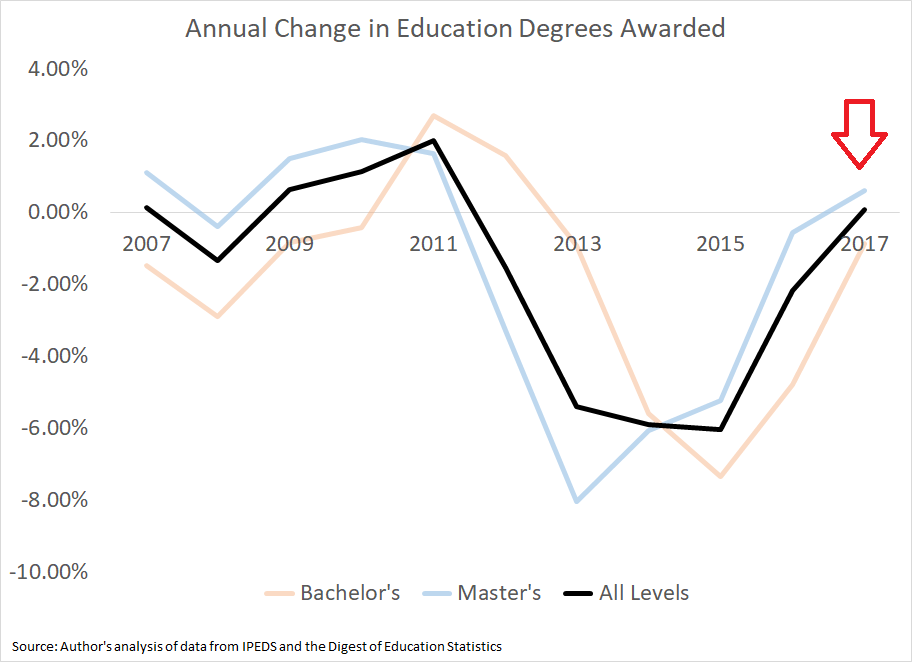

National data are starting to confirm these anecdotes. The most recent national statistics we have on new teacher licensures come from 2015-16, but we now have provisional data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System on college completions for the 2016-17 school year. Those numbers show a promising trend. After bottoming out in 2013, the year-over-year changes in the number of students completing an education degree got smaller and smaller. And in 2017, the most recent year for which we have data, we had the first year-over-year increase in college graduates with education degrees since 2012. It’s still not much — 2017 was just .62 percent higher than 2016 — but it could be the start of a promising trend.

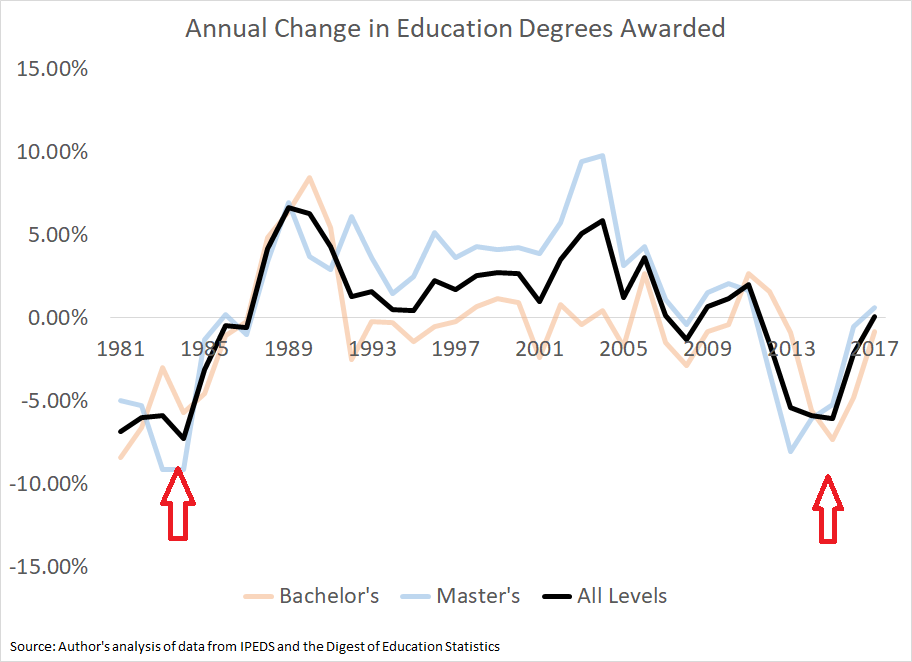

It has been a while, but this story has played out in American schools before. In the early 1980s, the number of young people graduating with education degrees was declining by 5 to 9 percent year-over-year. But things started to look less bad by 1986, and then we had 20 straight years of gains from 1988 through 2007.

These trends also match up with survey results about whether parents would want their children to become teachers. Just like the number of education degrees, answers to that question bottomed out in the early 1980s, rebounded in the late 1980s and remained high throughout most of the 1990s and early 2000s. Although those survey results hit a new low last year, the increase in the number of college students pursuing education degrees may portend another rise in the perceptions of parents.

Now, I’m not saying we’re likely to see the same stretch of gains in terms of perceptions or results we saw in the 1990s and early 2000s. That would depend on lots of other factors, including the number of college-age students and future economic conditions.

Nor am I saying the teacher labor market is perfectly balanced today. Even if the supply of new teacher candidates is starting to improve, it still may not match the growing demand for new educators. And as Kaitlin Pennington McVey and Justin Trinidad noted in a report for Bellwether Education Partners in January, some subject areas are chronically short of high-quality teacher candidates regardless of the underlying market conditions.

But these green shoots are an early indication that the teacher labor market may be starting to thaw. We’ll have to wait for more data to confirm these preliminary findings, but there’s reason to be hopeful that we’re on a positive trajectory.

[Read more at The 74] Read MoreNew Numbers Show Low-Income Students at Most of America’s Largest Charter School Networks Graduating College at Two to Four Times the National Average

A fresh look at the college success records at the major charter networks serving low-income students shows alumni earning bachelor’s degrees at rates up to four times as high as the 11 percent rate expected for that student population.

The ability of the high-performing networks to make good on the promise their founders made to struggling parents years ago — Send us your kids and we will get them to and through college — was something I first reported on two years ago in The Alumni.

Writing the new book I’m about to publish with The 74, The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending the Diploma Disparity Can Change the Face of America, provided the chance to go back and revisit those results. (You can track B.A. Breakthrough updates here.)

The baseline comparison number is slightly different but still dismal — just 11 percent of low-income students will graduate from college within six years — while for the big, nonprofit charter networks that serve high-poverty, minority students, most of them in major cities, the rates range from somewhat better to four times better and, in some cases, even higher.

The improved chances of earning a degree held while the ranks of charter alumni grew and the data became more robust. In some cases, the numbers are getting stronger and at least one prominent network, Uncommon Schools, predicts its graduates will close the college completion gap with affluent students in the next several years and surpass it a few years after that.

“Our mission is to get students to graduate from college, and that has influenced everything we do while we have students in elementary, middle and high school,” said Uncommon CEO Brett Peiser. “We’ve learned a lot about what works in helping students succeed in college, and everyone is focused on that goal.”

Ever since the first charter school was launched in Minnesota 27 years ago, educators watching the experiment have asked the same question: What lessons do they offer traditional school districts? Now, we may have that answer: Greatly improved odds that their alumni will earn college degrees.

Assuming that the charter completion rates persist, there’s a reasonable chance that their lessons learned could transform the way traditional school districts see their obligations to their graduates: How do they fare in college, and what effective methods from the charters could they start adopting to improve their outcomes later in life? Currently, almost no traditional districts track their alumni through college, although those in New York, Miami and Newark are moving in that direction.

All these issues get laid out in The B.A. Breakthrough. The book’s theme: The college success strategies pioneered by these charter networks are combining with entrepreneurial programs to spread data-driven college advising to high school students who lack it and with a growing commitment from colleges and universities to embrace low-income, first-generation students and ensure they walk away with degrees despite their vulnerabilities. Together these efforts add up to a breakthrough.

The charter network leg of the breakthrough

Given that college success is measured at the six-year mark, only recently has it become possible to evaluate the charter networks. In 2017, The 74 published a first-ever look at those rates as part of its series, The Alumni.

As with that project, the 11 percent college success rate used for comparison comes from The Pell Institute. That statistic provides an imprecise measurement, however, because it doesn’t take into account that most of these charter students are not just low-income, but also minority students living in urban neighborhoods whose college completion odds are even more daunting.

Comparing college graduation rates across charter networks is not easily done. KIPP, for example, tracks all alumni who completed eighth grade with KIPP, regardless of whether they go on to a KIPP high school. That puts KIPP in a category by itself. The other networks use the traditional approach of tracking only their high school graduates.

Even among the charter networks that track their high schoolers from graduation day, there are significant variations. While all the networks draw on the same foundational source, the National Student Clearinghouse, which matches the IDs of high school graduates to enrolled college students, some networks invest in their own tracking system, which picks up students missed by the Clearinghouse system. That makes their data more accurate and likely to produce higher rates.

Given the complexities, I divide the charter data into three groups:

Category 1 — Tracking from eighth grade, record-keeping that KIPP says is necessary to account for dropouts:

KIPP (national): As of the fall of 2017, KIPP had 3,200 alumni who were six years out of high school. The network’s national college completion rate is 36 percent for all alumni who completed eighth grade at a KIPP school and 45 percent for those who graduated from a KIPP high school. That counts students who entered a KIPP high school in ninth grade and stayed a year or more. In the national group, another 5 percent earned two-year degrees; in the group that graduated from a KIPP high school, another 6 percent earned two-year degrees.

Category 2 — Networks that use both Clearinghouse and internal tracking data:

Uplift Education (North Texas): Thirty-seven percent of the 1,075 graduates of the classes of 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014 earned bachelor’s degrees within six years. When associate’s degrees are included, that climbs to 40 percent. If calculated just on the classes of 2011 and 2012, the rate would be 57 percent.

Uncommon Schools (New Jersey and New York): Fifty-four percent of their alumni earn a bachelor’s degree within six years. Among those, 39 percent earn a bachelor’s within four years. Drawing on data that track students currently enrolled, Uncommon predicts that it will close the college graduation gap with high-income students (58 percent) in the next few years. Within six years, Uncommon expects to hit a success rate of 70 percent.

DSST Public Schools (Denver): Among the 1,075 alumni, starting with the class of 2011, half earned bachelor’s degrees within six years.

YES Prep (Houston): The network has 974 alumni from the graduating classes of 2001-2012. Among the earliest graduating classes (2001-2008), 52 percent earned a two- or four-year degree within six years of high school graduation. Of the most recent graduating classes (2009-2012), 40 percent earned a four-year degree and 6 percent earned a two-year degree within six years of high school graduation.

Noble Network of Charter Schools (Chicago): Noble has 2,259 alumni who are six years or more out of high school. Among that group, 35 percent have bachelor’s degrees, 7 percent have associate’s degrees and 9 percent are still in college.

Category 3 — Charter networks that rely solely on National Student Clearinghouse data:

Achievement First (New York, Connecticut and Rhode Island): There were 74 alumni from the classes of 2010-12. Of those, 34 percent earned bachelor’s degrees within six years. Another 2 percent earned associate’s degrees.

Green Dot Public Schools (California): Green Dot has 6,601 alumni from the classes of 2004-2012. Of those, 14 percent earned bachelor’s degrees by the six-year mark. Another 15 percent completed two-year degrees. (Green Dot has a less aggressive college success program than other networks, and, as seen in its absorption of the failing Locke High School in Watts, it takes on significant challenges.)

Aspire Public Schools (California and Tennessee): Aspire has 619 alumni from the classes of 2007-2012 who have reached the six-year point. Of those, 26 percent earned bachelor’s degrees, a rate that rises to 36 percent when associate’s degrees and certificates are included.

Alliance College-Ready Public Schools (California): At Alliance, 610 of their 2,617 alumni have reached the six-year point. Of those, 23 percent have earned four-year degrees. When two-year degrees are added in, the percentage rises to 27.

IDEA Public Schools (Texas, Louisiana): At IDEA, 508 alumni have reached the six-year mark. Of those, 38 percent earned bachelor’s degrees. Another 4 percent earned associate’s degrees in that time. (Another 2 percent earned either a bachelor’s degree or an associate’s, but it’s unclear which, due to reporting issues.) The network says it is experiencing steady improvements: Whereas only 31 percent of 2009 IDEA graduates completed college in six years, 50 percent of its 2012 graduates did.

Single charter schools:

There are a few solo charters, not part of networks, with significant numbers of alumni who have passed the six-year mark.

One example from Boston, a city which has some of the longest-running charters, is Boston Collegiate Charter School. There, 51 percent of the 177 alumni six years out earned bachelor’s degrees; another 8 percent earned two-year degrees. The school appears to be experiencing sharp increases in success rates: For the class of 2014, 79 percent graduated from college within four years.

More on the data

Consider this an early take on the promise charters made to offer better odds on college success. For many of the networks, the number of alumni who have reached the six-year mark is modest. We’ll know more as larger classes graduate and reach that milestone.

Comparing the networks is difficult because some use internal tracking systems that pick up students missed by the Clearinghouse. For example, networks using only Clearinghouse data miss students exercising their privacy rights, known as “FERPA blocks” for the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. That shields their college transcripts from outside review. In a time when immigration issues are contentious and parents (and some students) could face deportation, FERPA blocks are an attractive option for families. The number of blocks varies greatly by region, with few on the East Coast exercising the option and as high as 6 percent of all students attending West Coast colleges opting to shield their records, according to the Clearinghouse.

Translation: Charter networks such as IDEA Public Schools, with many of its schools located in Texas border towns, that also rely only the Clearinghouse data, are likely to show lower success rates.

Also tricky: When comparing the charter alumni to the broader student population, what’s the right comparison number to choose? The 11 percent Pell number I’m using should be viewed as a rough marker. First, that makes the denominator all low-income students — not just low-income high school graduates — which suggests the 11 percent figure is low. But the fact that most of these networks enroll minority students from urban neighborhoods suggests 11 percent is high because the Pell number would include low-income Asian and white students, who across income levels have higher college graduation rates than black and Hispanic students. Bottom line: The 11 percent emerges as a useful if imprecise comparison figure.

Watching a network do the math

By necessity, all the college graduation data are self-reported. Outcome figures from the National Student Clearinghouse, which is private, are proprietary to the networks, which pay the Clearinghouse for the information. For the sake of transparency, I asked one network, Uncommon Schools, to open up its books for me so I could observe both processes, the Clearinghouse data combined with its own tracking data.

In April 2018, I met Ken Herrera, Uncommon’s senior director of data analytics, in Newark at North Star Academy Charter School. There, Herrera clicked on his laptop and showed me a listing of alumni. For privacy reasons, the students had been “de-identified” and showed up only as numbers on the modified Salesforce (the customized business software Uncommon and other networks use to track their alumni) program. Twice a year, said Herrera, usually in March and October, Uncommon sends a list of alumni names and their dates of birth to the Clearinghouse for tracking. Why just some? Because Uncommon saves money by omitting names of alumni who, for example, already had their college graduation confirmed through a university. In about two weeks, the Clearinghouse sends back an Excel sheet with the information it collected on the asked-about students: where they are in school and what term — fall semester, for example — they are in.

If Herrera sees a “no match,” which happens about 10 percent of the time, he and the counselors investigate. At networks that don’t track alumni individually, that student would be counted as a dropout. When digging into it further, Uncommon finds out whether they truly have dropped out by contacting the university or the family or the student, whatever means is available. They also track down whether it’s just a matter of having entered the wrong birth date or a name mix-up, such as a nickname used when enrolling in college. If it is just a bookkeeping issue, the counselors request a copy of the college transcript so the error can get fixed.

Another reason for the “no match” might be the FERPA block, which prompts the Uncommon team to contact the students and convince them to unblock their records. Some universities make records disclosure an opt-in process, done every semester, which makes life especially difficult for Herrera, because if the student fails to take action the default status is a FERPA block.

In early April each year, Herrera meets with the counseling team to sort out data omissions, a painstaking, student-by-student process. “We’ll say, ‘This is what the Clearinghouse says about the student, here’s what Salesforce says about the student. What are we going to do about this conflict?’” That leads to a counselor personally investigating: Where is the student? When all the data issues get settled, Uncommon can calculate its college success figure.

Now the trickier issue: Unlike most other networks, Uncommon predicts where its college success rate is headed. Here’s what Uncommon predicts, as noted above: In roughly six years, the college success rate will rise to about 70 percent. Given that 70 percent exceeds the rate for well-off white students, that’s a remarkable prediction. What’s it based on? Uncommon tracks its alumni by cohorts, so it can establish a historical rate for, let’s say, how many students drop out between their freshman and sophomore year in college.

“When we look at each of those [dropout points] we can predict where an individual cohort is going, based on those historical rates, and predict what we think their graduation rate is going to be,” Herrera said.

Currently, Uncommon is seeing significant improvements, such as half the historical rate of dropouts between the sophomore and junior years. Also an issue: Uncommon is growing. By the year 2022, it projects 1,000 graduates a year, compared with the roughly 400 current graduates. That also figures into the math, because younger cohorts, which are showing better persistence rates, have a bigger impact on the overall college success math. The newer cohort, for example, is showing a 50 percent success rate at the four-year mark (older cohorts achieved that only at the six-year mark). Thus the prediction: 70 percent overall success rate within six years.

So why the improved persistence? Most of that, says Herrera, comes from strengthening the high school curriculum and programs such as Target 3.0, a mandatory class to boost the grade point averages for all students with a GPA less than 2.5.

“What we found, perhaps unsurprisingly to many people, but I think really profoundly for us, was that students with higher GPAs were more likely to graduate from college,” he said. “When we cut the data, getting above a 3.0 GPA [in high school] was very significantly correlated with future college success.”

Where all this leads

Yes, it is early to be judging college success among these networks, but not premature. There are thousands of alumni in these calculations, and their academic outcomes are crucial. If their success persists and, more importantly, if their lessons learned are picked up by the far larger traditional school districts, we could be looking at one of the most successful anti-poverty programs ever seen in this country.

There’s no guarantee it will happen, but the seeds are there, all explained in the upcoming The B.A. Breakthrough.

[Read more at The 74] Read MoreAre Teacher Shortages Worse Than We Thought?

The teacher shortage is “worse than we thought,” researchers conclude in a new analysis of federal data.

The study, published by the union-backed think tank Economic Policy Institute, argues that when indicators of teacher quality are considered—like experience, certification, and training—the teacher shortage is even more acute than previously estimated. This hits high-poverty schools the hardest, the study’s authors say.

However, other researchers have pushed back against the idea of a national teacher shortage, arguing that shortages are localized and concentrated in certain subjects, like special education and high school math and science. A 2013 analysis by Education Week found that colleges are overproducing elementary teachers.

“We don’t have a national teacher labor market, we have 50 different labor markets,” said Daniel Goldhaber, the director of the Center for Education Data and Research at the University of Washington.

And in most states, the teaching force has actually grown faster than student enrollment.

Still, Elaine Weiss, a co-author of the EPI report and the former national coordinator for the Broader Bolder Approach to Education campaign, noted that schools across the country have reported difficulties hiring teachers. An Education Week analysis of federal data found that all 50 states reported experiencing statewide shortages in at least one teaching area for either the 2016-17 or 2017-18 school year.

“If schools are reporting that they need teachers, and that they are struggling to find teachers to fill those spots, … I find it very hard to understand how there can’t be a teacher shortage,” Weiss said.

A few years ago, the Learning Policy Institute, a K-12 think tank led by Linda Darling-Hammond, who is now the chairwoman of California’s board of education, released a package of reports that projected an annual national shortfall of 112,000 teachers by 2018. The need for more educators would continue to grow well into the 2020s, the group predicted.

These estimates likely underestimate the magnitude of the problem, the EPI report says, because they consider how many new qualified teachers are needed to meet new demand. But not all current teachers are highly qualified—a term that, according to the report, means they’re fully certified, they were prepared through a traditional-certification program, they have more than five years experience, and they have relevant experience in the subject they teach.

Goldhaber pushed back against the LPI study, saying the methodology used was flawed and the projections have not materialized: There aren’t currently more than 100,000 people missing from the teaching force, he said.

Still, certain subjects (like special education, high school science and math, foreign language, and bilingual education) and locations (like high-poverty and rural areas) perennially lack teachers. The EPI report doesn’t delve into shortages in subject areas, but it does focus on the growing lack of highly qualified teachers in high-poverty schools.

Who and Where Are ‘Highly Qualified’ Teachers?

“Highly qualified” was, for many years, an important technical term with the force of law behind it. The prior federal law, the No Child Left Behind Act, defined highly qualified teachers as those who held a bachelor’s degree, state certification, and have demonstrated content knowledge. The law required that states staff each core academic class with those teachers. But NCLB’s replacement, the Every Student Succeeds Act, threw out that requirement.

Instead, ESSA says that teachers in schools receiving Title I funds just need to fulfill their state’s licensing requirements. States are also required to define “ineffective,” “out-of-field,” and “inexperienced” teachers, and make sure that poor and minority students aren’t being taught by a disproportionate number of them.

The EPI report expands the NCLB definition of highly qualified teachers to include experience and preparation. The number of teachers who meet EPI’s criteria of highly qualified has declined over time, according to the group’s analysis of federal data.

Alternative-certification programs bring in more teachers of color, male teachers, and teachers who attended selective colleges than traditional prep programs do, past reports have found. But research has also found that alternatively certified teachers quit at higher rates and report feeling less prepared than their traditionally certified colleagues.

The shortage of teachers who meet all these criteria is most pronounced in high-poverty schools, the EPI report finds. For example, 80 percent of teachers in low-poverty schools have more than five years of experience, compared to 75 percent of teachers in high-poverty schools. And about 73 percent of teachers who work in low-poverty schools have an educational background in the subject they teach, compared to 66 percent of teachers in high-poverty schools.

It’s worth noting that high-poverty schools struggle with hiring and retaining teachers in general—not just teachers who meet EPI’s criteria of highly qualified.

But the study’s authors write that highly qualified teachers are in high demand, and are more likely to be recruited by affluent school districts that might be able to offer better working conditions. Low-income children are consistently more likely to be taught by teachers who are not fully certified or who have less experience, the report says.

Indeed, a federal 2016 report found that uncertified teachers were more prevalent among high-poverty schools and schools with high percentages of students of color and English-language learners.

The EPI authors are planning to release five more papers analyzing the conditions that contribute to the shortage of who they deem highly qualified teachers, particularly in high-poverty schools. The papers will look at challenges related to teacher recruitment, pay, working conditions, and professional development, as well as give recommendations to policymakers.

(The National Education Association and the American Federation of Teachers are some of EPI’s top donors. The think tank gets about 30 percent of its funding from unions, and the rest from foundations, individuals, and other organizations.)

These papers are coming at a time when teachers across the country have been protesting against low wages and crumbling classrooms, Weiss noted.

[Read more at Education Week] Read MoreMemphis parent advocacy group spreading model to other cities, most recently Nashville

Sonya Thomas met a handful of fellow Nashville parents last summer, and quickly realized they all had something in common – a deep dissatisfaction with the schools their kids were attending.

Thomas said they wanted to do something big and drastic, something more than just talking about it. But they didn’t know what that was until they met Sarah Carpenter, a vocal Memphis parent and leader of advocacy group Memphis Lift, at a Nashville parent summit.

“The thing that most stood out to me, is how much they help their other parents,” said Golding Chalix, one of the leaders of the new parent advocacy group Nashville Propel. “To me, that was really inspiring to see parents fighting and working toward goals in a more organized way, especially being a Latina mom wanting to fight this fight.”

Nashville is the latest city to copy pieces of the Memphis Lift model. Carpenter said she’s been meeting with parents in Oakland and Atlanta to help get their programs started. An Indianapolis nonprofit launched an advocacy fellowship earlier this year to give low-income families and families of color more voice in their local schools – and pointed to Memphis Lift as one of the model examples of parent engagement work.

The handful of parents that make up the backbone of Nashville Propel started meeting last fall, and held a joint press conference with Memphis Lift last week at Capitol Hill to talk about their priorities, which hinge on educating parents of students in Nashville’s lowest-performing schools.

Memphis Lift has had success in reaching parents door-to-door and building a grassroots support system through its own advocacy fellowship. The group has held dozen of events at its North Memphis headquarters, at schools, and has shown up in force to school board meetings as its sought to rally parents.

Carpenter, who helped start Memphis Lift in 2015, said the national interest started three years ago when she spoke at a Teach for America event.

“Our phones have been ringing off the hook since,” Carpenter said. “It’s awesome to connect with other parents like this who have the same problems. They’re regular parents just like us trying to make a change in their city for low-performing schools.”

Thomas said the Nashville group is copying Memphis Lift’s strategies in door-to-door outreach and from its Public Advocate Fellowship, which was created three years ago by Natasha Kamrani and John Little, who came to Memphis from Nashville to train local parents to become advocates for school equity.

When Memphis Lift launched, it was viewed warily by some local school leaders who doubted the group’s independence because of its close relationship with Kamrani, former director of Tennessee’s branch of Democrats For Education Reform and wife of Chris Barbic, founding superintendent of the Achievement School District. Little ran Strategy Redefined, a Nashville-based education consultant firm that helped launch Memphis Lift.

The Memphis fellowship has trained 327 members, mostly women, since it launchedin 2015 on how to navigate an increasingly complex school choice system and how to understand state data on schools. This past year, Memphis Lift offered training for Spanish-speaking parents and is working to create its first all-male cohort for fathers and grandfathers.

Nashville Propel just finished its first parent fellowship, which was completed by 29 English and Spanish speakers. Thomas said a big goal for Propel is to help parents understand what it means that their children attend priority schools, the state’s designation for Tennessee’s lowest-performing schools.

PHOTO: Nashville PropelOn March 9, members of the Nashville Propel joined together to officially launch their group.

“We’re finding parents don’t clearly understand what this means,” Thomas said. “Some even think priority school means their school is doing well. Once we explain it to them, they realize the gravity of it.”

With neighborhood events over the last few months, Nashville Propel has spoken with about 700 priority-school parents. Within a year, the group wants reach 4,000, which is 75 percent of Nashville parents whose kids go to low-performing schools, Thomas said.

Tremayne Haymer of Nashville Propel said they are going to advocate for Metro Nashville Public Schools to release a public plan for the city’s 21 priority schools. Six Nashville schools were on the list in 2012.

“From 2011 to now, every time the list comes out the number gets greater,” Haymer said. “We’re going to be in the same boat Memphis was in a few years ago. Our plan is a year from now to get clear-cut resources from the district on how to combat this problem.”

Unlike Memphis Lift, Nashville Propel does not yet have a full time staff, but Haymer said they are actively looking for funders. Haymer added that Propel has gotten some startup funding from the Scarlett Family Foundation, which focuses its education philanthropy on Middle Tennessee.

Memphis Lift has received $1.5 million from the Walton foundation since 2015, and its fellowships are funded in part by the Memphis Education Fund. (Chalkbeat also receives support from local philanthropies connected to Memphis Education Fund and The Walton Family Foundation. You can learn more about our funding here.)

Despite initial leeriness toward Memphis Lift’s funders, the group has criticized and supported both district and state-run schools over the years, such as marching against the closure of an Achievement School District charter school and lobbying county commissioners last year for more funding for Memphis’ traditional school district.

“If it’s a charter school not working, close it down,” Carpenter said. “If it’s a district school not working, do the same. We want it shut down, period. We know what our children deserve in an education.”

Thomas echoed the sentiment.

“We’re not pro-traditional schools, private schools or charter schools,” Thomas said. “We have no other agenda except empowered parents whose children are taken care of.”

[Read more at Chalkbeat] Read MoreNew teachers often get the students who are furthest behind — and that’s a problem for both

Being a new teacher is notoriously difficult — and schools often make it even tougher.

New research out of Los Angeles finds that teachers in their first few years end up in classrooms with more struggling students and in schools with fewer experienced colleagues, making their introduction to teaching all the more challenging.

The differences between the environments of new teachers and their more experienced teachers are generally small, but they appear to matter for both students and teachers. The tougher assignments hurt new teachers’ performance and their career trajectories — and mean that students who are the furthest behind are being taught by the least experienced educators.

It’s a long-standing issue that states and districts have struggled to address and that concerns civil rights groups.

“More than anything else in schools, teaching quality has greatest impact on student achievement and student success,” said Allison Socol of the Education Trust. “And we know that the impact of strong teachers is greater for students who are further behind academically.”

The latest study is notable in scope, looking at a decade of data on teachers in the country’s second-largest school district. The researchers compared newer teachers to teachers who had been in the classroom for six years or more, from the 2007-08 school year until 2016-17.

They found that first-year teachers served more struggling students — those who started the year with lower test scores, lower grades, and higher suspension and absence rates — than more experienced teachers. The differences were small but consistent.

Novice middle and high school teachers were also more likely to work with students learning English (7 percentage points more), students from low-income families (6 percentage points), and students with disabilities (1 percentage point). And it’s not just a first-year effect: the results generally hold for teachers in years two through five.

This isn’t simply because younger teachers work in entirely different schools. Often, novice teachers are serving more disadvantaged students than their veteran colleagues down the hall.

“One of the things we see is that the stronger teachers or the more experienced teachers are often the ones who teach the advanced classes,” said Socol, referring to research on the issue more broadly.

Teachers usually improve with experience, particularly in their first few years, so the latest results mean that students who are struggling the most are often getting the least qualified teachers.

Los Angeles Unified, responding to the fundings, said its staffers try to assign teachers fairly.

“Los Angeles Unified has counselors at schools and counseling coordinators at our six local districts who prepare master schedules that are equitable for students and built around the skills and competencies of our teachers,” Los Angeles deputy superintendent Vivian Ekchian said in a statement. “National Board Certified teachers, mentor teachers and coaches work closely with our novice teachers to support them in their career development.”

New teachers didn’t have tougher jobs by every metric. While novice elementary school teachers had slightly larger class sizes, middle and high school teachers had smaller classes (by about 1.5 students) and fewer distinct courses to prepare for than their more experienced colleagues.

But newer teachers also tended to have colleagues who had less experience and lower evaluation ratings themselves.

The researchers demonstrate that new teachers in more challenging contexts also performed worse, missed more days of school, and were more likely to leave their school. That means that new teachers’ assignments matter both in the short term — for how they perform in their classrooms — and in the long term, for whether they stay there.

Again, though, the impact was fairly small: About 20 percent of teachers departed their schools by the end of the year, and that fell by 1 point for teachers with less difficult workloads.

“Retention and support of teachers, especially novice teachers, has critical implications for school operations and, in turn, student learning and achievement,” write the researchers, Paul Bruno and Sarah Rabovsky of the University of Southern California and Katharine Strunk of Michigan State University.

The results overlap with past research showing that students from low-income families and students of color get less qualified and effective teachers, though these disparities are often modest.

Still, Socol of Education Trust said, “We know that these gaps aren’t inevitable.”

What could help? Not assigning new teachers to the most demanding classes, perhaps, and making sure they have a network of effective colleagues. Past research has suggested that better principals and more collaborative school environments can help teachers improve and encourage them to remain in the classroom.

“It’s very much about the systems of supports that we provide for those novice teachers,” said Socol.

Improving teacher preparation could help, too. Research has found that pairing student teachers with effective mentors can boost novice teachers’ skills.

Studies have shown that bonuses designed to get effective teachers to transfer intoand stay in high-needs classrooms can help reduce the share of novice teachers in those classrooms.

Many of these strategies cost money. In Los Angeles, teachers recently went on strikein part over complaints about inadequate resources.

“We should situate this in a broader conversation about about resource equity,” said Socol. “It’s really important that we equitably allocate dollars … to the schools and districts to the schools and districts that need them the most.”

[Read more at Chalkbeat] Read MoreMetro Nashville Public Schools has most students with two consecutive ineffective teachers

NASHVILLE, Tenn.–A new report from the Tennessee Comptroller’s Office finds public school students taught by ineffective teachers two years consecutively affected their performance.

TCOT conducted the study at the request of Senator Dolores Gresham. The study found over 8,000 students -1.6% of all students in the study- had a teacher with low evaluation scores in the 2013-14 and 2014-15 school years in math, English, or both subjects.

In English language arts, grade 6 to grade 7 students had the highest number and percentage of students with consecutive ineffective teachers. In math, grade 8 to grade 9 students had the highest percentage of consecutive ineffective teachers. Statewide, Algebra I students overall had the lowest access to effective teachers.

The study found the district with the highest number of students with two ineffective teachers was Metro Nashville Public Schools. The district was found to have 1,055 such students representing 2.78% of the population. Hamilton County Schools was second with 3.60% of students.

Percentage-wise, Decatur and Johnson counties led the state with 10% or more of students having two consecutive ineffective teachers.

The study found students with such teachers were less likely than their peers to be proficient or advanced on state assessment testing when students had ineffective teachers for two consecutive years.

Students who were English language learners, in special education, or in high-poverty schools were 50% more likely to have two consecutive ineffective teachers.

[Read more at Fox 17 Nashville] Read MoreRepublican Bill Haslam and DE Democrat Jack Markell, See a Bipartisan Path Forward on Schools, Standards & Prioritizing ‘Education Across the Aisle’

Can a Republican and a Democrat see eye-to-eye on education? Former Govs. Bill Haslam of Tennessee and Jack Markell found that yes, they can, during a wide-ranging one-on-one discussion titled “Education Across the Aisle.” The governors, who were brought together by the Collaborative for Student Success, covered five topics of critical importance in American education: college and career readiness, standards, testing, the current state of education and the Every Student Succeeds Act.

The Collaborative shared a transcript of the conversation with The 74, which we are presenting as a first-of-its-kind two-person 74 Interview. The transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

On college and career readiness:

Gov. Bill Haslam: When you look back, what do you see as the thing that made the most substantial difference of all the policies you put in place?

Gov. Jack Markell: I think one of the things that underlay all the policies was the fact that we were more honest with our students and parents about what it really takes these days to be successful after high school. That’s a huge deal, because for so long, people have set the bar so low when it comes to educational attainment, and we’ve got to keep raising that bar.

Haslam: We’ve had a historical issue with that in Tennessee, of not setting our expectations high enough. What did you do to change that in Delaware?

Markell: First, we went around the state, and we had conversations about stronger schools. We talked about what’s going on around the world and the fact that our students are not just competing with other students from Delaware or from the mid-Atlantic region — they’re competing with the best of the best anywhere. If they were going to compete successfully, it meant we had to have higher standards and the kind of assessments that would reflect how they’re doing.

Haslam: That was our challenge as well. The year before I came in, the United States Chamber of Commerce gave Tennessee an F for truth in advertising. We were saying that 70 percent of our kids were proficient at grade level, but when those same kids got to community college, 70 percent of them needed remedial work. There’s no way both of those things were true.

Markell: A lot of people told me it was a political mistake to have this conversation with the people of Delaware about what it really means to be proficient. But my view was, if you really explained how the world around us is changing and what those changes mean, and showed that we’ve got to act differently, that at the end of the day, it’s the right thing to do.

Haslam: How would you tell somebody to have the political courage to have those difficult conversations?

Markell: You have to know what it’s worth losing an election over. We all want to win our reelection, but sometimes if you have really tough conversations, it may not go your way at the ballot box. But my experience has been that if you’re honest with people, and if you tell them why you’re making changes, they’ll be with you. The other thing is, you have to have a sense of humility. None of us has all the answers. One of the most important things we did is we went out and listened. We asked a lot of questions of parents, teachers and people throughout the business community about what kind of future they envision for their kids and for the state.

Haslam: How did you tie in preparation for the job market in a rapidly changing world to your education vision?

Markell: This is something that everybody understands. Everybody wants their kids, when they finish high school, to be ready for college or for a career. So one of the most important things we did is we brought the business community together with the higher eds and K-12 systems. That doesn’t sound very complicated, but frankly, those conversations just had not really been taking place around the country. I think that they should. It’s really important for the businesses to take a very active role in defining the types of skills they’re going to value.

Haslam: How did you get higher ed to be nimble and reactive enough to what the businesses were telling them they needed?

Markell: We started with the community college. It’s very powerful to bring education leaders into a room with business leaders who are talking about the kinds of skills that they need, the kinds that they’re not getting today. If you ask, “How good a job are our higher institutions doing in terms of preparing young people for the future?” Education administrators, 90 percent of them say we’re doing a great job. Business leaders, 10 percent of them say we’re doing a great job.

Haslam: We built off this Tennessee promise of having said, “You can have access to higher education,” but for a lot of families, that was like, “OK, we’re going there, but where is that going to lead me?” Our community colleges are speed boats compared to the battleships of trying to turn around a four-year university. But our four-year universities are reacting as well.

I was elected in 2010. My first year, 2011, unemployment’s at 9.5, 10 percent. It was literally just about finding jobs that would come to our state. Now, it’s dramatically changed. The jobs are there, and they’re wanting to know, “Can you give me the workforce that I need?” That’s become one of my primary roles — the person standing between these businesses we’re recruiting and the community colleges, four-years and technical schools. I feel like my role is much more of a bridge now than it was when I was just out begging to get jobs.

Markell: Exactly. I’d like to be a marriage broker, because virtually every day as governor, I’d have two sets of conversations. One would be with an employer who’s saying, “I have these vacancies, but I can’t find people to fill them.” And the other set of conversations would be with individuals, maybe they were formerly incarcerated, maybe they were returning veterans, maybe they had disabilities, maybe they were youth who didn’t get the kind of education they should have gotten, saying, “All I want is a shot, and nobody’s giving me a shot.” And the fact is, with the job market being what it is today, we’ve got to do a better job of building a new pipeline of employees of talent.

Haslam: There’s talk about how divided the country is, and yet you did a nice job of working across the aisle. My sense is that the country’s not only divided, but we’re mad about how divided we are. We’re mad that the other half doesn’t think like we do. So how did you, particularly on the education issue, bridge that divide?

Markell: I thought it was very important to get out beyond the legislature to explain to the people of my state a very clear worldview: “Here’s how the world around us is changing, here’s what these changes mean for all of us and here’s what we need to do differently as a result.” For me, that worldview is very much about two massive forces at work on our economy. One is globalization, which means employers have more choices than they’ve ever had before about where to hire people. The other is technology, which means they need relatively fewer people. When it comes to education, it means we have no choice other than to invest massively in skill development. And so, even if the people disagree with the things you propose, they at least understand where you’re coming from.

On standards:

Haslam: You were there around some of the pushback around Common Core, but, like us, you were able to fight past that, set some standards that you could agree to and have some things that were more strictly identified with Delaware. How did you get that accomplished?

Markell: One thing that was helpful was we invited community leaders into our schools, where they got to sit in on actual Common Core-[aligned] lessons taught by actual teachers. As the people were leaving, they said, “Boy, that certainly seems a whole lot like a math class or an English class. That didn’t seem like some people trying to take over our government through our education system.”

Haslam: But, within that [process], obviously you’re working with the teachers who are maybe the most important piece of that. There were times when, I’m guessing, they were your partners and times when they felt like they were on the other side of the fence. How did you manage that?

Markell: I always try to be respectful, and when I had teachers say that they really did not agree with something that I was proposing, I would invite them into the office. I think it’s really important to be accessible, and for them to know that you’re listening. We really tried to make sure the focus was always on the kids. Teachers have a lot of insight about what’s in the best interest of the kids. We consulted a lot with the State Teachers of the Year. We’d get them together once a month, and I would often try to just sit in on those sessions and listen, because they had so much to add.

One thing that we also really focused on was professional development. Teachers got sick and tired of the professional development where there are 100 teachers staring at the front of the room and somebody’s talking to them. So we redesigned professional development. Every teacher in the state would sit down for 45 minutes or 90 minutes a week with a group of five peers, and they would drill into what the data was telling them about student performance.

Our states were the first two states to win Race to the Top. Part of what you were doing was defending the gains that were made, but then trying to take it to a whole other level.

Haslam: My predecessor, Gov. [Phil] Bredesen, was a different party — Democrat — but [his administration] had worked really hard to do things that I always told my Republican friends, “Hey, that’s stuff we believe in.”

They did three things, and we stuck to those. They raised the standards, what we expected every child to know. They worked really hard to get an assessment that matched those standards. And the third piece, it was very controversial and still is, they made certain the teacher’s evaluation was tied to how much the students learned during the year. It was based on a lot of things, but a piece of it was that.

Those have been the three keys in Tennessee. They were all part of our Race to the Top application. Again, people say that’s a Democratic initiative, the Race to the Top. But, I say, “No, that’s stuff we should believe in.” My job was to say, “Wait, we have made historic progress here, let’s not go back to where we were before.” We still have a long way to go, but I said, “We’ve made this great progress, let’s not go back.”

Markell: When you think about the next governor coming in, what’s your advice about how they should prioritize?

Haslam: Make certain you don’t give on your standards. We have a lot of teachers who said, “You’re expecting too much out of our kids, our kids aren’t like that.” Don’t accept that. No. 2, make sure the assessment matches, and make sure an evaluation counts what the students have learned.

On testing:

Haslam: One of the controversies around education today is, “You rely on testing so heavily, and we’re spending too much time testing our kids.” What was your response?

Markell: My response was, “Let’s be smart about the testing.” We need these high-quality assessments. But it’s possible that we’re testing too much in other places. So we provided some funding to each of our districts to do an inventory of assessments. What we really want is the assessments to be helpful to teachers, so they can identify where their students are falling behind. But that has to be paired with the right kind of professional development as well.

We had a bill that passed both houses, and that I ended up vetoing, to allow parents to opt out of these assessments. That was a tough fight. It’s easy to be against the tests — I get it. But at the same time, if we don’t have these high-quality assessments, it’s not possible for us to be honest with these students, with their parents, with the teachers, about where they’re going to go from here.

Haslam: I think that’s so well said. If we’re going to be serious about saying how much a student’s learned, then we have to have that. There are always going to be issues with it, but it’s a little like saying the scoreboard didn’t work, so we’re going to quit keeping score in high school football.

Markell: We also used a sports analogy. We used basketball, and when you set the standards low, it’s like having a basketball player practice by shooting at an 8-foot basket. They can get really great shooting at an 8-foot basket, but then they get into the game, and they’re competing against people who have been practicing on a regulation basket, and they don’t do too well. Look at where we rank compared to countries all around the world, and there’s no question that the states and the countries that do a better job of educating today are going to outcompete tomorrow.

On the current state of education:

Haslam: Now that you’re stepped back, and you look across the education scene nationally, how do you assess where we are today?

Markell: I’m worried about where we are nationally on education because I think the narrative is not going in the direction we want. I believe that the kinds of things that you did in Tennessee — setting high standards, having the courage to have the quality assessments that go with them — have to undergird everything else we do. I just think it is too easy to run away from them.

Haslam: We went through historic period in our country when we had a Republican president, George W. Bush, who set No Child Left Behind. I know people had some issues with it, but the premise was really fundamental and radical for a Republican president. They were saying, “No matter what zip code you’re in, I think you deserve the chance for a great education.” And so we started measuring achievement gaps between minority and non-minority students and looking at a lot of things we hadn’t before. All based on: Let’s measure, what does the data tell us about what that child’s actually learning? Eight years of that idea, which again, was a pretty radical transformation, I think for the better.

Then you had a Democrat president, Obama, come in and do something even more radical. As a Democrat president, he went against the teachers union, particularly on this whole idea of evaluations tied to how much students were learning. Teachers unions have traditionally been huge Democrat funders, and he went against that and said, “Outcomes matter if we’re going to have an opportunity where every child can learn.”

Those were 16 historic years in our country. I think the thing that distressed me about the 2016 election was we really didn’t have a discussion about public education. You had Bernie Sanders talking about free college for everybody, and Secretary Clinton picked up on that. But, in terms of what we need to do in public K-12 education, it was crickets out there. That concerned me.

Doing hard stuff is hard. When you put higher standards and great assessments out there, there are a lot of people that don’t want that to happen, and they can use time to erode gains.

On ESSA:

Markell: For the last couple years, the Every Student Succeeds Act has been a big part of what’s going on nationally. What are the most important things to making sure that states take fullest advantage of that law?

Haslam: You and I, we were able to make some hard decisions and say, “Well, the federal government says that we have to.” That’s gone away. Now it’s up to state and local governments. And it’s made it more important than ever that states know what direction they want to go, and then local government is the same way. Those local school board races have never been more important.

Markell: As governor, how did you interact with the local boards with respect to the Every Student Succeeds Act?

Haslam: When we were putting our plan together, every state had to get their ESSA plan approved, and our Commission of Education reached down and talked to all the different school districts to say, “Here’s what we’re thinking, here’s what the plan will look like.” Because of that, we were able to have a plan that was approved very quickly. But I don’t think you could understate that it’s a very, very different world than it was in 2011, when Race to the Top was being implemented. The federal role is dramatically minimized compared to that.

Markell: And if states do what they should, that’s going to be a good thing.

Haslam: That’s right. There’s more accountability on us than ever before.

Markell: You’ve achieved some remarkable progress in Tennessee. For states to achieve that kind of progress, the schools that are having the most difficult time have to achieve real improvements. How have you made that happen?

Haslam: We’ve had some places where we’ve succeeded and some places where we haven’t. Turning around schools is really difficult. We have a saying in our Department of Education that we’ve kind of clung to, and that’s, “All means all.” When we’re talking about “all kids,” it means all kids, regardless of zip code or disability or anything else. So we can’t accept, “Well, that’s just a historically underperforming school.”

But I think it’s really about recruiting great leaders for those schools. Having a great school is like having a great restaurant, a great hospital, a great bank, a great church or synagogue. The quality of the leader determines what that is like. And so, it’s about, “How do we go find a great leader for that school?”

Markell: It’s true. If you show me a great school, you’re also showing me a great leader.

Haslam: It’s about great leaders, ratcheting up autonomy, and ratcheting up accountability. Do those three things, and we’ll figure out the rest.

[Read more at The 74] Read MoreChallenging Conventional Wisdom, New Report Suggests Diversity of America’s Teaching Force Has Not Kept Pace With Population

Taking aim at the perception that efforts to diversify the teaching profession are working, a new study by the Brookings Institution shows that the educator workforce is growing disproportionately white over time.

The analysis, released last week, offers a counterintuitive finding since the educator workforce has become more diverse in recent years — a fact researchers from Brookings’s Brown Center on Education Policy don’t dispute. Roughly 20 percent of educators are now nonwhite, up from roughly 12 percent in the late 1980s. But as the American population becomes increasingly diverse, the share of nonwhite teachers has failed to keep pace with the racial demographics of America’s college-educated workforce, researchers found.

Based on 25 years of Census Bureau data, researchers challenge the assertion that the profession has become more attractive to teachers of color. The finding is concerning since the diversity of teachers has failed to keep pace with the racial makeup of the students in their classrooms, said report co-author Michael Hansen, a senior fellow at Brookings and director of the Brown Center. Previous research has found that students tend to perform better in school when they have a teacher who shares their race or ethnicity.

“The biggest red flag to me, at least, is the mounting evidence on the value of having same-race teachers at least sometime within your trajectory,” he said. The latest report is part of a larger series at Brookings exploring the racial diversity of teachers. In a previous report, researchers found that racial segregation among educators is actually starker than it is for students. That’s because educators of color are typically steered to schools with high-minority student populations.

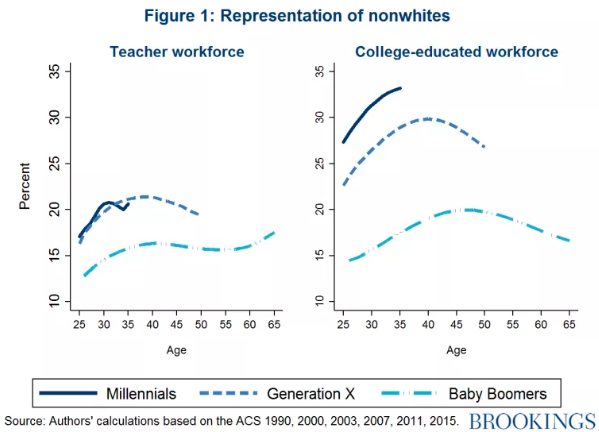

In the latest analysis, researchers found that part of the diversity problem falls on millennials. Though millennials are more racially diverse than older generations, whites make up a larger share of young teachers than they do baby boomer and Gen X educators.

It’s possible the diversity of millennial educators could grow over time. Across generations, researchers found that teachers are less diverse when they’re young but demographics shift as they age. Among older generations, teacher diversity appears to peak among educators in their late 30s and early 40s.

One possible explanation is that nonwhite groups tend to graduate from college later in life and therefore enter the teaching profession when they’re older. But the racial diversity of millennial teachers is “virtually identical” to the diversity of older generations when they were younger, researchers found.

Though the share of nonwhite educators has grown in recent years, the “increases in racial diversity are more due to the fact that Generation X and millennials in general are more diverse than prior generations, not because schools are getting better at attracting and retaining teachers of color,” according to the report. “In reality, teaching has grown slowly less attractive to people of color, as evidenced by the larger diversity gaps across generations.”

[Read more at The 74] Read MoreNew Coalition on Transition to Postsecondary

A new coalition of leaders from 18 education organizations, dubbed Level Up, is seeking to alleviate the “stubborn misalignment between K-12 and higher education that too often derails U.S. students from earning a postsecondary degree or credential and becoming economically self-sufficient.” The group wants to measurably increase numbers of high school students, particularly from underrepresented groups, who are prepared for and successfully complete postsecondary education and training programs. It will seek to do so through direct support and research, as well by supporting policies.

“We owe it to all students to not add burdens, frustrations and inefficiencies to their pursuit of something our society very much needs them to do: complete high school, earn a high-quality postsecondary certificate or degree, and enter the work force with the skills necessary to meaningfully contribute,” the coalition said in a new report.

[Read more at Inside Higher Ed] Read MoreWhat are the reading research insights that every educator should know?

If your district isn’t having an “uh oh” moment around reading instruction, it probably should be. Educators across the country are experiencing a collective awakening about literacy instruction, thanks to a recent tsunami of national media attention. Alarm bells are ringing—as they should be—because we’ve gotten some big things wrong: Research has documented what works to get kids to read, yet those evidence-based reading practices appear to be missing from most classrooms.

Systemic failures have left educators overwhelmingly unaware of the research on how kids learn to read. Many teacher-preparation programs lack effective reading training, something educators rightly lament once they get to the classroom. On personal blogs and social media, teachers often write of learning essential reading research years into their careers, with powerful expressions of dismay and betrayal that they weren’t taught sooner. Others express anger.

The lack of knowledge about the science of reading doesn’t just affect teachers. It’s perfectly possible to become a principal or even a district curriculum leader without first learning the key research. In fact, this was true for us.

We each learned critical reading research only after entering district leadership. Jared learned during school improvement work for a nonprofit, while between district leadership positions. When already a district leader, Brian learned from reading specialists when his district received grant-funded literacy support. Robin learned in her fourth year as a district leader, while doing research to prepare for a curriculum adoption.

Understanding the research has been crucial to our ability to lead districts to improved reading outcomes. Yet each of us could easily have missed out on that critical professional learning. If not for those unplanned learning experiences, we’d probably still be ignorant about how kids learn to read.

There’s no finishing school for chief academic officers, nor is there certification on literacy know-how for district and school leaders. Literacy experts have been recommending the same research-based approaches since the 2000 National Reading Panel report, yet there still aren’t systemic mechanisms for ensuring this information reaches the educators who set instructional directions and professional-development agendas. Why should we be surprised to find pervasive misunderstandings?

Here are five essential insights supported by reading research that educators should know—but all too often don’t:

- Grouping students by reading level is poorly supported by research, yet pervasive. For example, 9 out of 10 U.S. 15-year-olds attend schools that use the practice.

- Many teachers overspend instructional time on “skills and strategies” instruction, an emphasis that offers diminishing returns for student learning, according to a Learning First and the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy report this year.

- Students’ background knowledge is essential to reading comprehension. Curricula should help students build content knowledge in history and science, in order to empower reading success.

- Daily, systematic phonics instruction in early grades is recommended by the National Institute for Literacy, based on extensive evidence from the National Reading Panel.

- Proven strategies for getting all kids—including English-language learners, students with IEPs, and struggling readers—working with grade-level texts must be employed to ensure equitable literacy work.

Educator friends, if any of these statements make you scratch your head, you probably have some unfinished learning.

Educators urgently need a national movement for professional learning about reading. We should declare a No Shame Zone for this work—to make it safe for all educators to say, “I have unfinished learning around literacy.”

Superintendents should ask their literacy leaders if research insights are understood and implemented in their classrooms. They must be prepared to invest in the unfinished learning of their team, from teachers to cabinet. Surely some educators will defend misguided approaches; we all tend to believe we are doing the right thing, until research shows us otherwise. On this point, we speak from experience. We encourage superintendents to lean into the national conversation about literacy, in order to ask the right questions.

Some may characterize this national dialogue as reopening the “reading wars,” which pitted phonics against whole language. Frankly, we don’t see it. We don’t frequently hear educators in our districts vigorously defending whole language, as such. More often, they’re simply doing what they believe to work, without knowing better. Instead, we primarily face a battle against misunderstanding and lack of awareness.

For example, some express fears that phonics instruction comes at the expense of students engaging with rich texts, yet every good curriculum we know incorporates strong foundational skills and daily work with high-quality texts. The National Reading Panel got it right: Literacy work is a both/and, not either/or.

The battle against misunderstanding can be won by pairing professional learning with improved curriculum. Quality curriculum that is tailor-built to the research makes good practice tangible and achievable for teachers. Professional development around implementation of such high-quality curriculum is where it all comes together: Teachers are given the what to use, and professional learning explains the why and the how of those materials.

Districts today have many choices among research-aligned, excellent curricula, which was not the case even two years ago. These new curriculum options may be the catalyst we need to improve reading instruction. In each of our districts, we have implemented one of the newly available curricula that earned the highest possible rating by EdReports, a curriculum review nonprofit. Districtwide reading improvement followed.

The gap between good and mediocre curricula is vast. And district teams need a collective understanding of how kids learn to read before selecting new materials. The advances we have personally seen from high-quality curricula have led us to call for a national professional-learning network around curricula to foster cross-district collaboration.

We dream of the potential for children if we embrace this moment of unfinished learning.

[Read more at Education Week] Read More