Nashville schools interim director taps Tennessee’s Achievement School District chief for top post

In a major coup for Nashville public schools, interim Director Adrienne Battle is appointing the state’s education turnaround czar to a top Cabinet position.

Sharon Griffin, who heads the state-run Achievement School District, will join Metro Nashville Public Schools on July 1 as the chief of innovation.

As well, Hank Clay, Communities in Schools of Tennessee CEO, will rejoin the district as chief of staff on July 1, replacing Marcy Singer-Gabella.

The high-profile moves show Battle’s desire to leave a stamp on the operations of the district after securing a two-year interim contract. While the board could decide to start a search at any time, Battle’s appointment is a signal she doesn’t plan to be just a caretaker of the district.

Under the district’s previous interim director, top positions were left unfilled or were appointed in the interim.

“I think what is clear to everyone is (Griffin’s) track record and her work in the turnaround space with the iZone work in Shelby County,” she said.

And she cited Clay’s institutional knowledge of MNPS and his connections with statewide resources as part of why she hired him.

Battle’s decision to bring in the two won praise from at least one school board member. Board member Gini Pupo-Walker said Battle is showing through both hires that she wants to make district improvements immediately and spoke highly of Griffin.

“Adrienne Battle is not your average or ordinary interim,” Pupo-Walker said.”Her (Griffin) coming to MNPS signals she believes in Adrienne, but it also shows the urgency Adrienne has.”

Griffin’s departure from the state’s turnaround district

Griffin’s move, however, means more leadership woes for the ASD. The state will need to find a fourth replacement to lead the district in as many years.

The Tennessee Department of Education will appoint an interim within the next week, said Amity Schuyler, a deputy commissioner who helps oversee the ASD. Griffin’s last day as ASD chief is June 28, according to her resignation letter.

Schuyler said the state Education Department will embark on a national search for a replacement and could have a new leader in place as early as January.

Schuyler said the turnover of leadership in recent years is a concern.

“Changes of leadership have to be managed carefully,” Schuyler said. “You are hoping to get a leader that will stick around and remain committed in the long term. It is hard work, and it is understandable that turnover is more frequent than desired.”

A top school turnaround expert

Nashville public schools will get a leader who is recognized as one of the top school improvement experts in the state. Griffin was tapped in 2018 by former Tennessee Education Commissioner Candice McQueen to lead the ASD.

The Achievement School District is the state district tasked with taking over and improving the bottom 5% performing Tennessee schools in terms of academic achievement.

The ASD works mostly in Memphis and employs a more hands-off approach by using primarily charter schools. Nashville has two ASD schools operated by LEAD Public Schools, a charter management organization.

Since her appointment, Griffin has sought to align the district’s work with the best research practices. She has also sought to ensure the charter schools tasked with running the ASD schools have a stronger teaching staff.

Marty McGreal, who oversees Pathways in Education, a school in the Achievement School District, said he is sad to see Griffin leave.

“She gets kids,” he said. “She really, really gets it. She stops by a lot. Not as many people get it right away.”

The leadership position also placed Griffin in a role where she helped advise low-performing schools, even if they weren’t part of the ASD.

Before her stint leading the ASD, she served as Shelby County Schools’ chief of schools, overseeing direct support to schools, principals and teachers.

In Shelby County, she helped lead the iZone, which is known nationally for making strong improvements among Memphis’ lowest-performing schools.

Battle reorganizes the central office

Clay heads to Nashville schools after previously serving under former Superintendent Jesse Register as an assistant to the director.

Clay has led Communities in Schools of Tennessee for two years. The nonprofit works statewide to help connect community resources and ensure students stay in school.

Battle said she will not fill the vacated chief of schools position formerly held by Sito Narcisse.

Her administrative Cabinet will also see changes, including appointing associate superintendents who oversee the elementary, middle and high schools.

[Read more at the Tennessean] Read MoreHere’s the No. 1 concern that Tennessee’s new education chief heard during her statewide listening tour

After visiting classrooms in 30 school districts across the state, talking regularly with superintendents and other stakeholders, and reviewing more than 25,000 comments from teachers, Tennessee’s new education commissioner says one theme keeps emerging: the need to support the mental health needs of students.

“Without question, it’s the No. 1 piece of feedback I heard from every single group,” Penny Schwinn told Chalkbeat this week. “There is a growing concern about how we can support our children, not only academically but also behaviorally.”

Student mental health — an issue that has received a lot of lip service in Tennessee in recent years, but little in the way of funding — is one of 12 priorities identified in the state education department’s proposed five-year strategic plan, released Friday.

“We have an increasing number of children living in predominantly low-income communities and also coming from environments of addiction or abuse. We’re seeing upticks in suicide rates and bullying behaviors,” Schwinn said.

The commissioner unveiled the first draft of what she calls a “roadmap for the future,” after conferring this week with superintendents during regional gatherings in East and Middle Tennessee. She’ll meet with district leaders in West Tennessee later this month.

Schwinn also is inviting all Tennesseans to offer their input via an online survey that ends on June 21. “The voices of our students, our educators, and our superintendents are throughout this document, and we want even more feedback,” she said.

The final strategic plan is scheduled to be released in late July.

In addition to mental health, the proposed version lays out other priorities, including strengthening the state’s pipeline of teachers, developing and retaining school leaders, defining pathways to give students opportunities after graduating from high school, supporting rural schools, engaging with families, and STEAM education, which stands for science, technology, engineering, the arts, and math.

When Schwinn left Texas in January to become Tennessee’s new education chief, she promised to “listen and learn” as she kicked off her tenure by touring three schools — one rural, one urban, and one suburban — on her very first day.

She’s since visited more than 175 classrooms statewide and says it’s important that the state’s next strategic plan is rooted in ground-level conversations in school communities, not top-down edicts from her department.

“Commissioner Schwinn has been very open and willing to listen in developing this proposal,” said Dale Lynch, executive director of the state superintendents group. “Right now, I’d give her two thumbs up.”

In a conference call with reporters on Friday, Schwinn identified classrooms, educators, schools, and community as the four main pillars that will set the plan’s parameters. Girding those are academic standards, testing, accountability, and teacher evaluations — four policy strategies that grew out of Tennessee’s overhaul of K-12 education as part of its federal Race to the Top award in 2010.

Those four policies — all of which have generated controversy at one time or another — are “foundational,” Schwinn told reporters, calling them “not something that’s up for discussion.”

But other strategies and needs are on the table.

For school improvement work, the draft calls for “restructuring school turnaround so that there is more shared ownership between the state and local districts.” That suggests that Tennessee could choose to rely less on the state-run Achievement School District — its most intensive model in which the state has taken over low-performing schools in Memphis and Nashville and converted them to charter schools — and more on “Partnership Zones,” a collaborative state-district approach that just finished its first year in Chattanooga.

The draft also suggests that rural schools will get more attention under the administration of Gov. Bill Lee, a farmer and businessman who attended public schools in rural Williamson County and has pledged to make additional investments in the state’s more remote areas.

“We have to take a really strong position around how we support educators in those communities,” Schwinn said.

The need to beef up student mental health services has been a topic of conversation in Tennessee, especially since 2018 when one former student’s shooting spree killed 17 people at a high school in Parkland, Florida. In response, then-Gov. Bill Haslam convened a task force on school safety and urged local districts to explore ways to step up support for students’ emotional needs. However, most of the $25 million in extra funding approved by legislators that year went to improving school security, including upgrades to door locks, entryways, and screening equipment.

More than a year later, Schwinn said it’s becoming more apparent that — whether it’s called mental health or the “whole child” approach — schools need to do more to help their students feel healthy, safe, engaged, supported, and challenged in order to achieve long-term success.

She recounted a powerful conversation with one student in Robertson County, north of Nashville, who told her: “What I need in my school is to have a buddy to eat lunch with in the cafeteria every day and an adult I can go to when I have a problem. Those would make all the difference.”

“Too many of our kids can’t say they have both of those things, and that’s something we have to take seriously,” Schwinn said. “We’ve got to find ways to better support them as they develop as people.”

[To read the first draft of the strategic plan visit Chalkbeat] Read MoreHow Can States and Districts Make Teacher-Leadership Roles More Effective?

Research has shown that teachers having leadership roles in their schools can lead to improved student achievement. So why not formalize those roles?

That’s the argument in a new report by the National Institute for Excellence in Teaching, a group that works to increase educator effectiveness. The group convened a panel discussion at the U.S. Capitol on Wednesday to discuss how state and district leaders can create sustainable systems of teacher leadership. This form of professional learning—in which an accomplished teacher is given instructional leadership responsibilities while still remaining in the classroom—has become popular in many places, but the NIET report says there is a lack of explicit guidance on how to use federal funding to build this capacity.

“We need to have a larger national conversation about how do we formalize what teacher leadership is, in a way that actually moves student growth,” said Candice McQueen, the CEO of NIET and the former education commissioner for Tennessee, in an interview. “Giving a title is not the end. Giving the title begins the conversation of, ‘Now, what capacity do you need to grow other teachers and serve on this leadership team?’ We see too often that we stop at, ‘OK, now you’re the teacher leader, … with no release time, no additional compensation, no coaching, no professional learning, and no clarity around goals that are now part of the vision for your particular role.'”

“When you do [teacher leadership] well, you get results,” she added. “We sometimes give teacher leadership a bad name by creating a title without any of these other components around it.”

Some of NIET’s recommendations for building these formal teacher leadership systems include:

- District leaders should work with teachers and principals to develop a clear vision for teacher leadership roles. This will help create buy-in.

- Teacher leadership can be funded through both Title I and Title II dollars. NIET recommends districts combine local, state, and federal funds into a single pool to support schoolwide goals.

- States should create sustainable, dedicated funding streams to support teacher leadership.

Iowa, for instance, invests nearly $160 million per year in the teacher-leadership system. Ryan Wise, the director of the Iowa Department of Education, said on the panel that there are more than 10,000 teachers serving in funded leadership roles.

“Formalizing these roles and having teacher leaders in every building has been the fuel to get things done,” Wise said.

For example, the state has been prioritizing early literacy, and making sure every student can read by the end of 3rd grade. To help spread that work, teacher leaders are trained in best practices and then can spread that information to other teachers.

In the 2019-20 school year, NIET will partner with about 90 districts to provide training and support as they implement the group’s instructional framework on teacher leadership. NIET runs a teacher-leadership system called TAP: The System for Teacher and Student Achievement, which puts high-performing teachers into “master teacher” and “mentor teacher” roles.

After all, Christina Jamison, a teacher leader in Grand Prairie High School in Texas, said one-size-fits-all district training is rarely useful for teachers.

“None of that is relevant to my work,” she said. “Being able to be a leader of professional development on my campus has allowed my students to grow exponentially. … Teachers want to know stuff that’s going to help them.”

Indeed, many teachers say that professional development delivered by facilitators from outside groups is often disrespectful to teachers’ expertise and experience.

“Teacher leaders can go to a conference and come back and teach what they learned,” said Ross Wiener, the executive director of the Education & Society Program at the Aspen Institute, in closing remarks. “No outside vendor can do that with that kind of cadence and that kind of credibility and level of context.”

[Read more at Education Week] Read MoreBill Gates eyes the work ahead for Tennessee in education during visit to Nashville

Tennessee is making strong improvements in raising academic achievement among its students, but Bill Gates believes there is plenty of work still ahead for the Volunteer State.

Improvements for the state over the last several years include changing its academic standards, curriculum and feedback to teachers, Gates said.

But low academic achievement in concentrated sections of urban areas and poor rural counties continue to plague the state. Tennessee is near the middle when compared nationally on academic achievement in math and reading.

“On a relative basis, Tennessee is still below average,” Gates said during a Friday interview in Nashville with The Tennessean. Gates, one of the world’s wealthiest men, pledged during the visit to continue investing millions of dollars in the state’s education through his foundation.

Nationally, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation focuses its education efforts on minority and low-income students near urban centers. The foundation has invested about $34 million in Tennessee statewide, with an emphasis in Memphis.

Gauging support for Gates Foundation work

The Gates Foundation works in higher education, K-12 and early learning in Tennessee and that is “one of the very few states that we do all those things,” he said.

The billionaire philanthropist came to Nashville on Friday as part of a flurry of meetings to gauge the climate under first-term Gov. Bill Lee, who was elected in August.

Gates said in his interview that his foundation focuses primarily on working with local and state governments. The effort can be difficult if they change priorities, he said.

But after Thursday and Friday in Tennessee, Gates indicated his foundation will continue to invest in the initiatives it is undertaking. Gates was encouraged by Lee — who hosted Gates Thursday at the governor’s residence — and said it looks as if there will be another seven years with a governor whose focus is on education.

“Tennessee is a big focus state for us because education has been prioritized,” Gates said. “I am not sure what we would have done if the governor didn’t have education as a priority, but he does so … we are committed to keep working here with the partners in Tennessee.”

Tennessee’s progress

He was complimentary of Tennessee for its collaboration, and also for tackling tough changes under Govs. Bill Haslam and Phil Bredesen. Tennessee is shown to be one of the few states from 2009-2015 seeing academic improvement in almost every county.

Recent changes — such as the state’s academic standards — need patience, he said.

“The lag time in all these educational-related things are very long and you have to stay the course,” he said.

The work in Tennessee

Over the course of a 35-minute interview, Gates touched on aspects of Tennessee’s work in education.

The foundation is spending money in higher education, Gates said, to help systems align resources for students. Nationally, he said he worries that more than a third of students are not ready for college.

In Tennessee, about 46% of students enter Tennessee’s colleges needing remediation in math. About 33% need remediation in reading.

“You shouldn’t have more than a third that needs remedial classes,” Gates said.

He said the state is delving into dual credit opportunities for students, which allow students to come out of high school either exposed to college classes or earning some type of college credit. Under Haslam, the state also embarked on a concentrated effort to help 55% of its residents earn a degree or certificate by 2025.

The Gates Foundation also is working heavily in early education in Tennessee, which has been the focus for districts such as Metro Nashville Public Schools and Shelby County Schools.

The quality of voluntary pre-Kindergarten programs across the state varies, but those two districts are showing strong results.

Gates and his visit to Chattanooga

Gates shared thoughts on Chattanooga’s efforts, which were also part of the reason he was in Tennessee for his two-day trip.

He applauded Chattanooga for its efforts to get businesses involved in education through a community effort.

“… I am a huge believer that communities, especially the private sector, if you draw them in that is where you get things done,” he said. “That is where get permission to raise the community tax rate.”

He also visited with students, whom he said were positive about their experiences but complained about teacher attrition and resources.

Students told him resources were focused on students either in the top or bottom 10%.

“They said the teachers are amazing, but then they would leave,” he said.

[Read more at the Tennessean] Read MoreGates Foundation Launches Postsecondary Value Commission in Hopes of Influencing the Ongoing Higher Ed Reauthorization in Congress

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is launching a new initiative to measure the value of higher education, an effort leaders hope will influence the ongoing federal debate over reauthorizing the Higher Education Act.

“This cannot, and must not, be done like any other report that we’ve heard, that goes right to the shelf and no one uses it,” said Mildred Garcia, co-chair of the new Commission on Value in Postsecondary Education and president of the American Association of State Colleges and Universities. “We intend to produce relevant, actionable information to help people make decisions.”

The goal is for the results to be used by students and families to make decisions about attaining higher education, by college leaders to determine how well their programs are performing, and by policymakers to help gauge the value of public investments, Garcia said on a call with reporters last week.

One of the groups the commission hopes will find the information immediately relevant: Congress, which is in the midst of rewriting the Higher Education Act.

“If we can provide that clear definition about college value,” one that can be measured and that has been created by a diverse group of advocates, “we definitely are hoping it will affect the higher ed reauthorization,” Garcia said.

Specifically, the definition of value the commission comes up with could help Congress make decisions about Pell Grants, the approximately $28 billion the federal government spends annually that helps support low-income students, and federal-state partnerships, which would incentivize states to maintain public investments in higher education in an effort to hold down costs for students.

Time, however, is not on their side. Reauthorization efforts on Capitol Hill have begun in earnest, with Senate education committee leaders reportedly releasing a draft of the bill later this month, but the Gates commission is not scheduled to produce its final report until mid-2020.

“We are going to be working through our value commission in real time, as there are conversations happening on Capitol Hill … To the extent that we can inform those conversations, we certainly will,” said Sue Desmond-Hellmann, CEO of the Gates Foundation and co-chair of the commission.

Gates will also use the commission’s definition of higher ed to judge future investment decisions, Desmond-Hellmann added.

The 30-member commission will emphasize the economic value of degrees, but it will also look at other factors like the better health outcomes, voting participation and critical thinking skills that correlate with higher ed attendance.

Most people would say they attend postsecondary education to enhance their career opportunities, Cheryl Oldham, vice president of education policy at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and a member of the commission, told The 74.

The economic measures that reflect better career opportunities are particularly important to the growing number of students who are older adults going back for additional education to boost their job prospects, rather than the traditional 18- to 22-year-old student entering right after high school, she added.

The Gates effort will go further than existing earnings data, such as the federal College Scorecard, which provides average earnings for graduates of every university. Beyond earnings, the value measurement will include things like employment and economic mobility, and how those outcomes vary across race, gender and family income.

Americans are increasingly worried about the value of a higher education, the Foundation said in press materials. It cited polling data that showed that a majority of respondents believe higher ed is going in the wrong direction, with “tuition costs too high” and “students not getting needed skills” as top reasons for that perception.

The economic value of higher education is much like the value of a healthy diet — widely recognized, but unavailable to some groups for reasons like community norms, inaccessibility and competing options, Desmond-Hellman said.

“Our goal is to uncomplicate the connection between higher education and economic opportunity,” she said.

[Read more at the 74] Read MoreThis senior signing day has nothing to do with athletics. Celebrate academics | Opinion

On May 16, LEAD Academy’s largest ever graduating class will walk across the stage at Belmont’s Curb Event Center for our sixth annual senior signing day.

Surrounded by parents, teachers and community members, these young men and women will declare to friends and family the next big step in their journey.

All of them have worked hard to determine this next best step, whether it be to a university, college, military or career pathway. All of them have overcome challenges to get here. And thanks to their hard work— we are pleased to say this is the sixth-straight year that 100% of LEAD’s eligible graduates have been accepted to college.

In some ways, this senior signing day is even more important to us at LEAD than graduation day–because we know our job does not end with high school graduation. Our goal is to prepare our students for the lifetime of opportunities ahead of them.

Nationally, students from low-income backgrounds, students of color and first-generation college attendees— the same students we serve in Nashville— are much less likely to complete a post-secondary degree than their middle-class peers.

We are not OK with that.

That’s why we are working to prepare every student, regardless of family background, socioeconomic status or zip code – to graduate with the knowledge and skills they need to be both Ready for College and Ready for Life.

That may be a revolutionary perspective for some. But our students deserve nothing less.

According to the Tennessee State Report Card, 35% of LEAD Academy graduates are considered truly “Ready Graduates,” which combines students who graduate on time and who also scored a 21 or above on the ACT–a widely accepted measure of college and career readiness.

That’s much higher than Metro Nashville’s district average of 24%, which also includes the highly selective academic magnet schools.

We are proud of the progress our school and students have made, but we are nowhere near done.

As we looked at our alumni data, we saw that some of the biggest barriers to post-high school completion aren’t just academic but related to what happens outside the classroom.

So we have developed a comprehensive approach to preparing students for their next step, with a focus on helping them make college and career decisions based on the very best fit— for their own unique goals and needs.

Our students actively participate in an intensive college seminar for all four years of high school. They research and evaluate college and career choices based on what is the best fit for them and make a decision based on five buckets—financial, academic, social, emotional and living. We challenge them to think through questions about paying for college, housing, study habits and classes, confidence and mental health. We challenge them to own their decision.

No one else is doing anything like this. We believe our LEAD college and career process is much more intentional and intensive—for both the student and the school. But we believe it makes a huge difference.

All of this leads up to Senior Signing Day, an opportunity for students to make a commitment to themselves, to their families and publicly to our school community. It is that one big day when every single year they’ve spent within our building is finally paying off.

That’s why we invite all of Nashville to come to our senior signing day and witness and celebrate as these students take this next big step in their journey. They’ve done the work both academically and personally to get here.

Please join us on May 16 at the Belmont Curb Event Center at 9:30 a.m. We hope you will come cheer our students on and see firsthand how the hard work of these students will pay huge dividends both for them and for our community in the years ahead.

[Read more at the Tennessean] Read MoreAs Free College Tuition Becomes a Popular Rallying Cry, ‘Tennessee Promise’ Hailed as Game Changer — but Equity Concerns Remain

Lake County, population 7,500, the bubble-shaped piece of land in Tennessee’s northwestern corner, is wrapped by the Missouri River that separates it from two bordering states. Tiptonville, its biggest town and county seat, has a state prison and a small tourist attraction noting the birthplace of rockabilly legend Carl Lee Perkins, best known for writing and releasing the original “Blue Suede Shoes.”

Lake County is also the state’s poorest: Nearly 43 percent of adults and 49 percent of children live in poverty. Further, it’s the least-educated county in the state; less than 12 percent of adults have at least an associate’s degree.

That’s the challenge facing Michelle Johnson and Tonya McKellar, the counselors at Lake County High School, who are trying to push the 45 members of the class of 2019 to continue their education. An essential part of their arsenal has been Tennessee Promise, a four-year-old program that covers tuition and fees at community college or technical school for any high school graduate in the state.

“It’s just the whole culture that we have to change, and that’s not just the students. It’s the county. It’s the parents. It’s everybody,” McKellar told The 74 during a visit in mid-December.

The program is part of former governor Bill Haslam’s “Drive to 55” initiative to get 55 percent of Tennessee residents to earn a college degree or certificate by 2025. The broader program, which also now includes free community college for adults without degrees, was initially billed as an economic development and workforce initiative to, as Haslam put it, “ensure Tennesseans get Tennessee jobs.”

But Tennessee Promise is also having an impact earlier in the educational pipeline, changing the college-going culture in the Volunteer State’s high schools, both rural and urban, advocates and counselors told The 74.

“I think Promise has been a game changer for the culture in high school. It’s no longer about if, it’s about where you’re going to college,” said Krissy DeAlejandro, executive director of TNAchieves, a nonprofit that runs the program’s required mentoring and college orientation programs in much of the state.

“We often hear from students who say, ‘I’m the first one in my family to go to college, and now my siblings want to go to college,’” she said.

The program is increasingly being looked at as a national model, as other states emulate and expand on Tennessee’s example and progressives have made free college tuition a political rallying cry.

Even within the state, the idea of “free college” recently became even more expansive, when the University of Tennessee in March announced free tuition at three of its campuses for students who meet certain academic requirements and whose families make less than $50,000 a year.

Though widely praised — including by former president Barack Obama, who sought to replicate it at the federal level — Tennessee Promise does have its critics, primarily those who say its benefits primarily flow to students from higher-income families rather than those most in need. Undocumented students aren’t eligible, and research has shown lingering equity gaps despite the program’s near-universal accessibility.

The class of 2019 is just the fifth eligible for the program, so research on its impacts on students’ K-12 experience isn’t yet available. A study of a similar program for students in Kalamazoo Public Schools in Michigan showed that it resulted in more credits earned, higher grades and fewer days in detention or suspended in high school, particularly for African-American students.

Across Tennessee, 63.4 percent of the class of 2017 enrolled in higher ed the fall immediately after graduating from high school, up 5 percentage points from the class of 2014, before the program began.

“More kids are thinking they can have the opportunity to go to college with the Tennessee Promise, where they wouldn’t have before,” said Johnson, the counselor at Lake County.

The program, the first in the country to offer nearly universal access to all graduates, has been a lifeline for students who didn’t take their academics seriously early in high school, said Yolanda Grant, a counselor at Ridgeway High School in Memphis for the past 12 years.

“We don’t want them to think that because I didn’t do my very best in ninth, 10th and 11th grade, I don’t have any options. So with the Tennessee Promise, they still have an option,” she said.

State higher ed officials don’t keep track of recipients’ class rankings or high school GPAs, but they have seen that students in the program tend to have ACT scores “on the lower end,” said Emily House, chief policy and strategy officer at the Tennessee Higher Education Commission.

Research that House and her colleagues at the state agency presented to the state legislature in March 2019 also showed that the rate of remediation in Tennessee colleges is on the rise, which she attributed to the expanded attendance pool, including those who got lower ACT scores.

Although many of those low-scoring students would’ve enrolled in college before Tennessee Promise, more are doing so now that community college is increasingly accepted as part of the higher ed landscape, she told The 74.

“At the student level, it’s shifting this level of conversation around what it means to go to college,” she said.

‘They didn’t know what they were missing’

Johnson and McKellar, the Lake County counselors, are zealous about completing applications for Tennessee Promise.

One hundred percent of the class completed the basic application forms before The 74’s visit in mid-December. The eight stragglers who hadn’t finished the federal financial aid application required at all colleges, and for Tennessee Promise, did so by the Feb. 1 deadline.

That effort to complete the Tennessee Promise application, with its early deadlines, means students benefit even if they don’t ultimately use the program, McKellar said.

“It gives you a mindset of ‘We’re all working together to get to a certain point,’ and it all gets done early. That’s a big push,” and it has helped students earn other scholarships, she said.

The push has made students more receptive to college in general, Johnson said. “I think before, they didn’t know what they were missing.”

Johnson and McKellar expect 60 to 70 percent of this year’s class to go on to some form of higher education. That’s up from the 43.1 percent of the class of 2017 who went immediately to higher ed, according to figures from the state Department of Education.

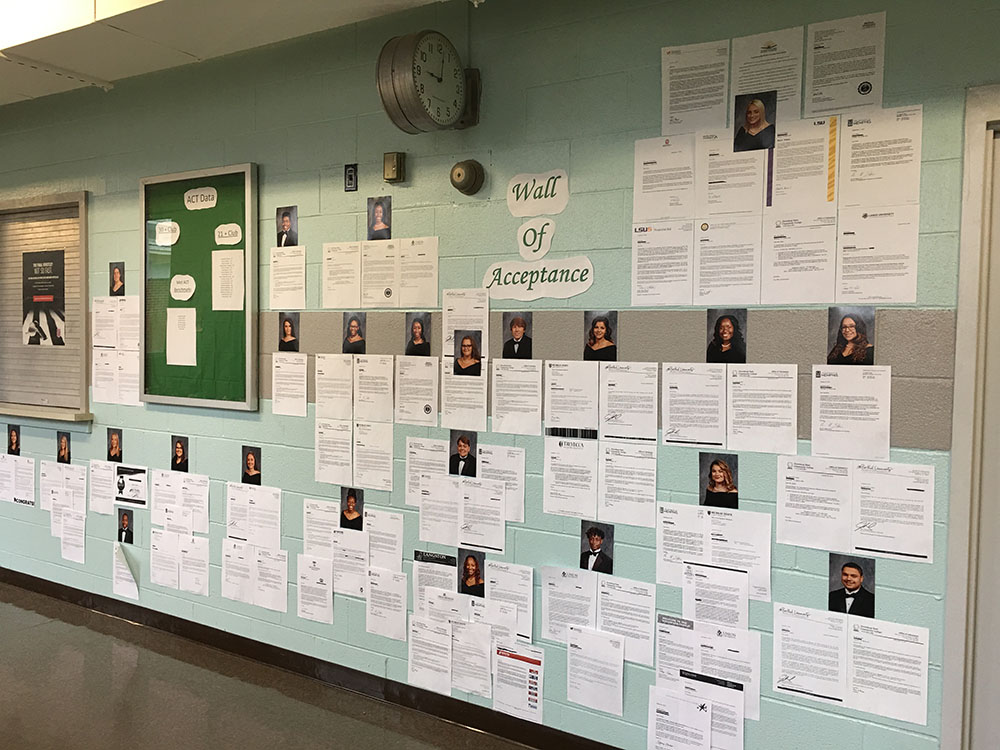

A wall at Lake County High School showcases where students have been accepted to college. (Michelle Johnson/Lake County Schools)

About half of the class of 2017 who went to higher ed attended community college, and the counselors say that’s likely to continue, with many headed to Dyersburg State Community College, a 30-minute drive from downtown Tiptonville.

Many students will use their two free years as a springboard to a four-year degree.

Johnson’s own daughter, who initially intended to spend all four years studying pre-K-3 education at a four-year school, decided to take advantage of the two free years at Dyersburg State before transferring.

But the opportunities come with a downside: Sending students out of Lake County for higher ed often means they won’t come back.

“There’s not a lot in Lake County, not a lot of opportunities in Lake County for folks with degrees” outside of education, Johnson said. “We have some very successful folks, but the majority of them stay out of Lake County.”

Though Johnson and McKellar encourage all students to maintain their Tennessee Promise eligibility, just in case of changed plans or family circumstances, only about 20 percent will actually use the grants. Many students, who come from very low-income families, will instead be covered by federal Pell Grants, Johnson said.

Tennessee Promise is what’s known as a “last-dollar” scholarship, meaning it covers tuition and fees only when other financial aid has run out. Pell provides up to $6,095 per year depending on family need. For many of the lowest-income students, Pell covers all the tuition and fees that would otherwise come from Tennessee Promise grants, so they don’t see any financial benefit from the program.

That lack of help to the neediest students is among the primary criticisms of the program. Advocates have argued that limited state dollars should be better targeted to the lowest-income students — for example, by paying for four-year degrees or helping with housing and living expenses that exceed Pell awards.

State officials say the lowest-income students do benefit.

“I understand the logic, because yes, these [Pell Grant-eligible] students don’t get [state] dollars. But I think even the lowest-income students get so much from this program,” including help filing their financial aid applications, mentoring and a general stronger college-going culture, House, the state higher ed official, said.

Memphis’s Ridgeway High School class of 2018 celebrates its graduation. The Tennessee Promise free community college has proved particularly valuable as a higher ed path for students who didn’t take academics as seriously early in their high school careers, staff said. (Shelby County Schools)

In an ideal world, all free college programs would be “first-dollar” and cover all college costs without considering other aid a student may receive, “but that is very rarely going to be politically feasible, financially feasible,” House added.

Both Johnson, at Lake County, and Grant, at Ridgeway, said they’ve helped low-income students who have encountered that problem. In the end, they say, it doesn’t particularly matter to the students where the money is coming from, so long as they get it.

Statewide research, on the other hand, showed that while the rate of community college completion has risen dramatically in the wake of Tennessee Promise, relatively few low-income students enroll in postsecondary education, and wide racial gaps in degree completion remain.

Physical access to Tennessee Promise-eligible schools has been an issue, too.

The northwestern corner of the state is particularly disadvantaged. Only 29 percent of Lake County residents have access to a community college within 25 miles, according to state figures.

Dyersburg State Community College, the most popular choice for Lake County students, is the closest, and students can also use Tennessee Promise to attend two nearby colleges of applied technology.

But beyond those schools, Lake County’s unique geography means that community colleges in bordering Missouri and Arkansas are closer than many in-state, Tennessee Promise-eligible schools.

State higher ed officials are keeping track of those higher ed deserts, House said, and are working with some K-12 districts to keep the buildings open for adult education offerings.

‘A backup plan’

It’s not just in rural Tennessee that the program is making a difference.

In Memphis, students at Ridgeway often say they had a plan to go to college but weren’t really putting anything into action before the additional push from Tennessee Promise, Vice Principal Taurin Hardy told The 74.

“Now they’re doing it. Now they know they have that financial stability, that financial backing. That’s a huge barrier for a lot of kids, especially kids of color,” he said.

For students who don’t need that extra reassurance, the program can also be something of a fallback.

As of mid-December, Alexis Jefferson, a Ridgeway senior, had been accepted into two four-year colleges where she hopes to study business and marketing, on her way to a job advertising toys. But if those don’t work out, she can use Tennessee Promise to study at Southwest Tennessee Community College.

“It’s sort of like a backup plan,” she said.

Such attitudes are a distinct shift from the early days of the program, when Tennessee Promise was a difficult sell, Grant, the Ridgeway counselor, said.

Students were put off by the stigma of community college as “13th grade” and not real college.

“Now it’s easy. They know that ‘I have an option. Although my parents may not be able to afford college, I can still go.’ For a lot of them, this is their No. 1 choice … They know they can still get a quality education,” she said.

[Read more at The 74] Read MoreTNReady tests expected to be included on student report cards after successful test year

Tennessee districts should have online TNReady scores available by the end of the school year, ensuring they can be used in student final grades.

Tennessee Department of Education spokesman Jay Klein said districts will get online raw scores for high schools to districts by May 20. Paper tests in grades 3-8 were required to be submitted on Monday to get results by that time.

Results will be delivered after the first TNReady online testing season that didn’t involve statewide problems.

About 2 million tests were completed statewide and almost 1.4 million were submitted online, according to a news release from Tennessee Education Commissioner Penny Schwinn. The state’s testing window closed on Friday.

The education department said in the announcement that there were minor issues in schools related to user error or local infrastructure limitations, but the state’s computer-based testing process was completed without a major incident.

This year’s testing window marks the first where Tennessee hasn’t had issues with its vendor and online testing.

Last year, the state saw widespread problems after Questar Assessment made unauthorized changes to the test platform.

Previous years also proved problematic. In 2017 Questar Assessment and the state didn’t deliver raw scores to districts on time.

And in 2016, then-test vendor Measurement, Inc. couldn’t handle the administration of online testing for the state. It caused the state to cancel testing in elementary and middle schools.

[Read more atTennessean] Read MoreBuilding On Tennessee’s Foundations For Student Success

Tennessee’s foundational policies in academic standards, annual assessment, and educator evaluation provide the fundamental building blocks of a high-quality education system. As Tennessee considers future opportunities to accelerate student learning, our collective commitment to these essential policies enable the practices and innovations that will propel our students to the success we all know they can achieve.

One of the priorities in the State Collaborative on Reforming Education (SCORE)’s 2018-19 State Of Education In Tennessee report focuses on Tennessee’s foundations for student success and the need to maintain the student-focused policies and practices that have driven unprecedented progress in student achievement, with greater emphasis on ensuring equity for all Tennesseans.

What were innovations a decade ago have become the bedrock for Tennessee’s current and future success. As Tennessee rebuilds confidence in the annual assessment system with students, educators, parents, and other education stakeholders, it is important to recognize how these policies have contributed to student success and the opportunities they present for Tennessee to build a world-class education system that gets better at getting better.

There is evidence that Tennessee students have learned more and educators have grown more during the time period that these policies were implemented when compared to other states:

- A Stanford University scholar’s in-depth analysis of student achievement trends across the country showed that from 2009-2015, Tennessee’s student achievement gains stood out both when comparing to other states and for the relative consistency of gains across Tennessee’s districts.

- Building on previous research by Brown University scholars, research from the Tennessee Education Research Alliance found that Tennessee teachers grew more in recent years, with Tennessee teachers improving more than their peers in other states.

- On the 2018 Tennessee Educator Survey, 69 percent of teachers said they believed Tennessee’s multiple measure teacher evaluation process led to improvements in their student learning. This is compared to 28 percent in 2012.

This unprecedented progress in both student and teacher growth is unique to Tennessee and suggests that the state has built the foundations for an education system that prioritizes and facilitates continuous improvement. It is a signal of Tennessee’s belief in the promise of what students and educators can achieve.

At the heart of these policies is how they help all students – regardless of where a student lives or their life circumstances – learn the skills and knowledge they need to be ready for college, career, and life. Tennessee’s academic standards provide a framework for rich learning experiences aligned to a thoughtful progression of concepts, skills, and content across grades. Combined with higher quality standards in other subjects, the standards provide a common set of expectations across the state while enabling local districts and educators to design the content-rich learning experiences students need.

With a clear set of learning goals, measuring student progress through an aligned, high-quality annual assessment allows students, parents, and educators to reflect on what was – and more importantly, was not – learned. The state’s current assessment, TNReady, has helped address Tennessee’s “honesty gap” and gives a more accurate snapshot of student learning.

In the past, the misalignment between the state’s test and national assessments of student learning helped hide inequities in learning outcomes for students of color, economically disadvantaged students, and students with disabilities. With implementation challenges in recent years, Tennessee deserves nothing less than a flawless TNReady administration in 2019 and beyond. Over time, each successful administration will help Tennesseans better understand and evaluate how well our public education system serves every student.

Research has consistently found that teachers and school leaders are the first and second most important in-school factors for student learning. Tennessee’s multiple measure evaluation system honors the essential role educators play in our education system by providing regular feedback on their practice from other educators as well as data on student learning.

When paired with high-quality professional learning, Tennessee’s educators get the support they need to grow as professionals. Local and state efforts to ensure equitable access to effective teaching, improve teacher preparation, and better develop teachers depend on a reliable understanding of teacher effectiveness. While more work remains to ensure observation feedback better matches current teacher needs, Tennessee educators overwhelmingly accept the premise that these evaluations help improve their craft. In future years, we will know even more about the work to improve teacher effectiveness because of Tennessee Education Research Alliance’s research.

The statewide alignment enables state policymakers to provide the right types of support to districts and educators without standing in the way of local innovations that improve student learning. From the 2020 English language arts instructional materials adoption to conversations about how to redesign the high school experience, districts and educators are empowered to design the opportunities that make the most sense for their communities while having a strong set of goals and processes to ensure that both students and teachers grow.

By adopting rigorous college and career ready standards for student learning, a high-quality assessment aligned to those standards, and a multiple-measure accountability system to provide feedback to educators, Tennessee created a policy environment that enables and encourages educators to deliver high-quality learning experiences year after year.

[Read More at SCORE] Read MoreSchool vouchers are coming to Nashville and Memphis: What it means for students and parents

A school voucher plan is coming to Tennessee’s two largest counties.

The education savings account program was a centerpiece of Gov. Bill Lee’s legislative agenda this year, and the General Assembly gave final approval to the plan on Wednesday.

The House and Senate had passed vastly different versions, and a conference committee gathered Wednesday morning, and after less than 30 minutes, approved a compromise that ironed out the differences.

On Twitter, Lee said the bill “provides more choices for more students and families.”

“This is an important day and I look forward to signing this bill into law,” Lee said.

So what’s in the final version of bill and how would it work? Here are some highlights:

What are education savings accounts?

Education savings accounts provide public money for parents who unenroll a student from their school district and allow them to use the funds on private school or other education-related expenses.ADVERTISING

Parents enrolling in the program would get debit-style cards to pay for tuition or the other approved expenses.

How much money would a student get?

On average, the state spends about $7,300 per student on education. That’s the amount, on average, a family would receive each year into their education savings account.

How many kids will be able to use the program?

The program, which would start in the 2021-22 school year, would apply to up to 15,000 by the program’s fifth year. Here’s how it would break down. BY THE SALVATION ARMYGetting rid of furniture? Don’t haul it yourself.See more →

- 5,000 students in the first year.

- 7,500 students in the second year.

- 10,000 students in the third year.

- 12,500 students in the fourth year.

- 15,000 students in the fifth year.

Which districts are targeted for the education savings account program?

Originally, students in five counties would have been eligible to participate in the program: Shelby, Davidson, Knox, Hamilton and Madison counties.

But later versions applied to just four and the final version only applies to Shelby and Davidson counties. In addition, students enrolled in schools overseen by the state-run Acheivement School District would also be eligible.

The ASD takes over the worst-performing schools in the state, and often turns operations of them over to charter schools, and largely works in Shelby and Davidson counties.

Are home-school students allowed to participate?

No. That was one of the differences lawmakers had to compromise on.

The Senate version of the bill allowed parents to unenroll a student from a public school and home-school them instead and use the education savings account for related expenses. The House version did not include that provision.

Are there testing requirements?

Yes. The bill only requires that students take the standardized math and English exams. It removed a House mandate that students in the program take the TNReady social studies and science tests.

Are there income requirements?

Yes, the program applies to low-income families. A student’s household income must meet the same requirements as the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program.

To verify eligibility, a household would have to provide a federal income tax return or proof that the parent of an eligible student is eligible to enroll in the temporary assistance program.

Eligibility, particularly whether a student who entered the country illegally as a child could participate, has been a sticking point for some lawmakers.

Sen. Todd Gardenhire, R-Chattanooga, blasted the legislation because of a provision that would prohibit families with undocumented students from receiving money. Gardenhire previously voted for the bill but switched to a no on Wednesday.

A 1982 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that says students who entered into the country illegally can’t be denied a public education. School districts do not ask the immigration status of students.

What responsibility do the districts have to your student if you participate?

In short, a district would have no responsibility to the parent if they unenroll children from their school.

Both bills say that parents must release the district from “all obligations to educate the participating student while participating in the program.”

What is the cost to the state?

That’s a good question. It all depends on how you account for the money and how many students participate in the program.

And lawmakers don’t agree, either, on the full cost. In fact, questions over a fiscal analysis of the bill forced Senators to delay their vote Wednesday. A new, updated analysis was later released.

At it’s core, here’s how the finances would work.

The plan would tie state funding for education to the student. In this case, the roughly $7,300 per student would go into the ESA.

The state would shift money away from Tennessee’s Basic Education Program to fund the education savings accounts. That’s all existing money, through a combination of state and local sources.

Then an equal amount of money would go into a new school improvement fund for three years starting in fiscal 2021-22 when students can begin enrolling.

That new fund would provide grants to Metro Nashville Public Schools and Shelby County Schools to make up for the money that the districts lose when the students participating in the ESA program leave a public school.

That’s new money — $165 million over three years based on full participation in the program. There would also be administrative costs.

But it’s not as simple as that.

The state is not projecting full participation in the program, and wants to set aside $25 million a year, plus money for administrative expenses, to cover the program’s costs.

[Read More at Tennessean] Read More