Tennessee Succeeds: Moving from “Good” to “Better” to “Best”

By Dr. Candice McQueen, Tennessee Commissioner of Education

Last Wednesday at our annual LEAD conference, I had the opportunity to share with hundreds of Tennessee’s educator leaders some of what I am thinking about as I have reflected on what I have learned over the past year. Through the highlights and lowlights, I keep coming back to a few key points:

- Our beliefs in students are incredibly important for shaping what happens in the classroom and the opportunities students have to learn.

- Curriculum is important, and we as leaders have to do a better job of making sure our teachers are not spending unnecessary time sourcing materials.

- But, teaching is the most important. What happens in the classroom every single day – how engaging our teaching is, how much it pushes students, how we go about driving learning – is the absolute most important part of what happens in education. We often do not spend enough time reflecting on our practice and how we can improve.

I continue to come back to the fundamental role of high standards in creating opportunities, and while I think we have done a lot of good work to meet those expectations, we can do better. We spend our time and energy on a lot of good things – but I want us to always ask if those are the best things.

I continue to come back to the fundamental role of high standards in creating opportunities, and while I think we have done a lot of good work to meet those expectations, we can do better. We spend our time and energy on a lot of good things – but I want us to always ask if those are the best things.

So, I want to share with you some of my prepared remarks from that speech for our continued and shared reflection on how each of us can continue to improve. This is a responsibility that we all share as educators, whether we are leading a class of students, supporting our teachers and students through an administrative role, or working at the state-level.

(The comments below are adapted from the prepared remarks for the 2018 LEAD conference.)

The Reason: Tennessee’s Students Deserve a World-Class Education

Each of our students has the same worth, and we therefore set the same expectations. Each of these students is equally deserving of a world-class education. Each wants to have the best teachers, the best books to read, the best science equipment, and the best field trips. They want to go to the best colleges and work in the best jobs. They want to become the best version of themselves.

When you ask them about their dreams, the vast majority of students and their families tell you they want to go to college. A national report that came out last week said that 94% of students are planning to go to college. Other surveys show that while many families want other students to have a variety of pathways after high school, for their child, they want them to go to a four-year college.

When you ask them about their dreams, the vast majority of students and their families tell you they want to go to college. A national report that came out last week said that 94% of students are planning to go to college. Other surveys show that while many families want other students to have a variety of pathways after high school, for their child, they want them to go to a four-year college.

So we have to ask ourselves: who is saying college isn’t for everyone? Is it really the students? Or is it us? I think we need to intentionally reflect on whether we are setting up opportunities and expectations for some students, but not for others. And when some students aren’t ready for postsecondary, we need to reflect on our own expectations and what role they may have played in what these students know and can do.

Let me be clear: I completely believe we have to make sure students are ready for a job when they leave high school. That is why we have put so much work into partnerships with career and technical industries and launching a new initiative focused on Tennessee Pathways. This is also why part of our accountability model includes career readiness in particular.

But we must honor the dreams and goals that students have. Those dreams can and often do change, but that should not be because we failed to make sure students were prepared for whatever they want to choose. Our job is to set them up for choice, not to make the choice for them. This is why our best opportunity to set them up for choice always has been and will continue to be great teaching and learning, for every student, every day.

The problem our students have – and the reason we are here – is they don’t know exactly how to reach those dreams. They don’t know how to plan for college and the workforce, and they don’t know how to get ready for the expectations that await them there.

That is what we are doing in K-12.

We are setting expectations every step along the way that make sure students are developing skills in literacy, math, social studies, science, music, foreign languages, and art. We are making sure they can make connections, think critically, and write articulately. These expectations all point to what colleges and employers say they need to know and be able to do to be successful.

We are setting expectations every step along the way that make sure students are developing skills in literacy, math, social studies, science, music, foreign languages, and art. We are making sure they can make connections, think critically, and write articulately. These expectations all point to what colleges and employers say they need to know and be able to do to be successful.

We are providing more counseling, starting in middle school, to make sure we hear students’ big dreams for themselves and help them make a plan for how they’ll get there.

We are creating a number of opportunities in high school, whether it be through work-based training or AP classes or dual enrollment, to provide students a chance to explore different fields and interest areas, gain college credit, and experience rigorous expectations – before they have to figure it out in a college classroom or on the job.

The Responsibility: Tennessee Students Need Us to Push Them to be Their Best

Students need us to set high expectations and expand opportunities, and they need us to support them in pursuing those – even if sometimes it means pushing them further than they thought they could go. This is our responsibility.

We are not doing kids a favor when we make it easier. Our students are too capable.

When we tell our students that they get a pass because it’s hard, or it may take a long time, or it didn’t work the first time, we are setting them up for failure after they graduate.

If we don’t push kids to meet high expectations, how will they be ready to write a college paper, handle calculus, annotate a text, design an experiment to solve a problem, or navigate complex machinery? How can we expect them to be critical thinkers who care about what is happening in their communities, figure out health care and housing, calculate payrolls, run trainings, launch the next business, or teach the next generation? How can we expect them to engage in thoughtful, lifelong civic discourse, give back to their communities, and never give up on solving problems, even if they didn’t create them?

If we don’t push kids to meet high expectations, how will they be ready to write a college paper, handle calculus, annotate a text, design an experiment to solve a problem, or navigate complex machinery? How can we expect them to be critical thinkers who care about what is happening in their communities, figure out health care and housing, calculate payrolls, run trainings, launch the next business, or teach the next generation? How can we expect them to engage in thoughtful, lifelong civic discourse, give back to their communities, and never give up on solving problems, even if they didn’t create them?

We can’t. We have to help teach them that often the best outcomes in school and in life happen when we reach the highest – even if we cannot quite reach the first time we try.

We must reject ‘the soft bigotry of low expectations.’

We know our students are resilient and capable. Many have already overcome more challenges than many of us have faced. They may have immigrated to this country because their neighborhood was under attack. They may have watched their parents go through layoffs when the garment industry left town. They may have seen loved ones die, parents working two jobs to get by, lost their house in a fire, or gone through tragedies of their own.

Talent, resilience, and academic ability is not inherent to any one class or race of students.

It is opportunity that tends to be unequally distributed.

That is our responsibility as teachers. To create more opportunities.

I want to spend some time with this question: How are we doing with fostering daily teaching and learning that aligns to our standards and sets high expectations for every child, which ultimately creates opportunities for students?

The answer is probably not well.

A report from TNTP that came out last we ek showed that students in a sample of schools across the country spent more than 500 hours per school year on assignments that weren’t appropriate for their grade and with instruction that didn’t ask enough of them. That is the equivalent of six months of wasted class time in each core subject.

ek showed that students in a sample of schools across the country spent more than 500 hours per school year on assignments that weren’t appropriate for their grade and with instruction that didn’t ask enough of them. That is the equivalent of six months of wasted class time in each core subject.

Perhaps even worse: the report found that underlying these weak experiences were low expectations: While more than 80 percent of teachers supported standards for college readiness in theory, less than half had the expectation that their students could reach that bar.

Students of color, those from low-income families, English language learners, and students with mild to moderate disabilities have even less access to quality instruction than their peers. Classrooms that served predominantly students from higher-income backgrounds spent twice as much time on grade-appropriate assignments and five times as much time with strong instruction, compared to classrooms with predominantly students from low-income backgrounds.

When students did have the chance to work on content that was appropriate for their grade, they rose to the occasion more often than not. Those chances paid off: In classrooms where students had greater access to grade-appropriate assignments, they gained nearly two months of additional learning compared to their peers.

That was what was seen nationally. In Tennessee, we did hundreds of literacy learning walks over the past year, which we used to gather insight into how Tennessee’s early grades classrooms were teaching reading. Those results were similarly pretty sobering.

Overall, the lessons we saw did not reflect the demands of the standards or the instructional shifts. Only 14 percent – just 14 percent – of classrooms had lessons that met the expectations in our standards. Just 2 percent did so all the time. That means 98 percent of our classrooms are not consistently teaching our academic expectations for students in early grades reading.

That is not how we set up students to be successful.

We know curriculum is important. And I want you to hear this: teaching matters more.

A study from a couple years back found that the schools that were improving had strong curriculum, yes, but they also had excellent teaching – and that is what pushed students further.

A study from a couple years back found that the schools that were improving had strong curriculum, yes, but they also had excellent teaching – and that is what pushed students further.

Each of us should be thinking about how our own teaching and the teaching in our building is meeting grade-level expectations. Our students need teachers to spend time reflecting on their practice rather than spending time looking for the next great worksheet or assignment or book.

How are we helping teachers recognize what strong, standards-aligned materials and instruction look like? I want to challenge us to think about how we make sure teachers are prioritizing their time on instruction, providing high-quality feedback, and modeling what high expectations looks like. We must support teachers in clearly understanding what students can and should be doing every day in our classrooms to meet those expectations. This is the most important role that administrators play, and too often, we are leaving teachers to figure it out by themselves and not developing teachers’ capacity to reflect and improve.

We know from our educator survey that teachers are spending a lot of time – too much time – sourcing materials. In the early grades, it’s around 5 hours a week. Only about two-thirds of them think the materials they have are well-suited to meet the expectations in the standards.

What would happen if teachers spent even just one or two of those hours that they currently need to spend on Pinterest or Teachers Pay Teachers reflecting on their instructional practice and planning for how they will guide the next day’s lesson? We want to be in a world where teachers can rely on high-quality curriculum that is already available to them, so they can spend that time reflecting on the data they’ve been gathering in their class and using it to improve. We want teachers to have the ability to spend less time on the “data collection” of providing assignments and tasks and more on the “data analysis” of student work.

If we do that, I think that could change what teaching and learning looks like. Dramatically.

So, how are you, as a teacher, as a leader, going to prioritize your time to keep teaching and learning at the center of what you think about and continuously improve? How are you as an administrator going to help the teachers in your building have capacity to focus on their instruction?

So, how are you, as a teacher, as a leader, going to prioritize your time to keep teaching and learning at the center of what you think about and continuously improve? How are you as an administrator going to help the teachers in your building have capacity to focus on their instruction?

Here is how we are thinking about those questions.

At the state, we launched a campaign called Ready with Resources that aims to make sure that all teachers have high-quality instructional materials so they can spend less time sourcing and more time focusing on how they are teaching. Ready with Resources also aims to make sure teachers have the professional development to use those materials and fully support standards-aligned instruction.

Think of it like this: Curriculum is like a paintbrush and palette. To make a beautiful painting, a teacher has to use the very best materials, and know the science behind them, but she also has to know how to put them together, how to react to unexpected results, and how to build on the piece to get a work of art.

The materials are important. But, the artist’s craft is even more so. That’s why great teaching is so critical.

I know this may feel easier said than done. I remember when I was in my first few years of teaching, my focus was not on reflecting on my teaching practice – it was on making the very best bulletin board I could. So, I know you may already be rehearsing in your head how you will respond to the push-back you’ll get when you talk about this at the faculty meeting next week. But let me remind you: our teachers, like all of us, are students, too, and there is so much potential and talent in those who work with our students every day. Improving teacher beliefs and their own growth mindsets matters to student success.

So, three things sum up our responsibility as educators:

- We must provide quality, aligned resources, materials, and tasks for our students

- We must increase teacher knowledge and skills

- And, we must improve teachers’ beliefs in themselves and in their students

When you close the door of the classroom, these are really the only three things that matter for teaching and learning.

So, I ask you, do you know the answers to each of these questions for every teacher in your care?

- Do your teachers believe in what each and every child can accomplish?

- Do your teachers have the knowledge and skills themselves to teach the expectations?

- And, do your teachers have the resources and materials to teach those expectations?

The Request: Be the Best We Can

As we close, I want to leave you with a couple of challenges to think about.

- Believe in our students, and believe in their potential. Push them to meet the expectations we have set for them – because they can.

- Maximize your time on what matters. That’s prioritizing teaching and learning, engaging with our work in Ready for Resources, and looking closely at student work and engagement.

We in education spend a lot of our time on “good” things. Finding high-quality texts – that’s a good thing. But I want to challenge us about how we spend our time on the best things.

It is good to give students an assignment that requires writing. It is better to require writing that pushes students to argue a point or share a position – and the earlier the exposure to this, the better. But, it is best to have students share these arguments based on texts and facts in writing and verbally, and then critique the arguments they wrote compared to others.

It is good to read to students and model fluency. It is even better to model fluency and ask questions that push beyond recall into inference and application. But, it is best to then have students read authentically and respond to high level questions about what they have read with direct feedback and dialogue with the teacher, other adults, and peers.

It is good to teach fractions using modeling. It is even better to teach fractions using modeling with direct comparisons to decimals and percentages. But, it is best to have students explain these comparisons with their own models.

I ask you: are you moving to the best we can offer students? Or are we settling for the good or maybe, just the better.

If we as teachers never get to the best of what we expect of students, the student may never get there on her own.It is like a coach that helps his runners eat right and practice daily – both good, but that approach accepts whatever happens at the race. Great coaches don’t do that – they work from the runner’s current personal best to set goals that the runner owns and pushes toward. Then, when the race occurs, the student gets feedback from the coach and works toward the goal again in new ways if he missed the mark, or, if he hit the goal, the runner is pushed to a better personal record. Great coaches don’t stop at good or even better – they push to the best. Great athletes almost always point to coaches that helped them see what was beyond their limited sight.

If we as teachers never get to the best of what we expect of students, the student may never get there on her own.It is like a coach that helps his runners eat right and practice daily – both good, but that approach accepts whatever happens at the race. Great coaches don’t do that – they work from the runner’s current personal best to set goals that the runner owns and pushes toward. Then, when the race occurs, the student gets feedback from the coach and works toward the goal again in new ways if he missed the mark, or, if he hit the goal, the runner is pushed to a better personal record. Great coaches don’t stop at good or even better – they push to the best. Great athletes almost always point to coaches that helped them see what was beyond their limited sight.

This is what I am asking you to do. Push your teachers and your students to the best they can offer. It is simply not ok to just understand the expectations of the standards and internalize the shift, but not practice the “new normal” in the classroom. Resources, materials, texts, math problems, projects, assignments have to change – you can’t get to best with the same tools.

This is where you come in – it is your responsibility to ensure the tools are the best.

We also can’t get to the best with the same educator skill sets and preparation. We have to grow and evolve as educators into new abilities. This takes rethinking professional learning and drawing more direct lines from what we do in PD to what we expect should happen in the classroom the next day.

Finally, we can’t get to best with the same expectations. Our students are incredible, and they are just asking us for a chance. There are any number of hurdles that are put in students’ pathways, and we as teachers should not let our own beliefs, stereotypes, or prejudices be one of those. If we set the bar high, our students will meet it. I know they can. High expectations are a daily belief, a daily mindset, a daily culture.

Finally, we can’t get to best with the same expectations. Our students are incredible, and they are just asking us for a chance. There are any number of hurdles that are put in students’ pathways, and we as teachers should not let our own beliefs, stereotypes, or prejudices be one of those. If we set the bar high, our students will meet it. I know they can. High expectations are a daily belief, a daily mindset, a daily culture.

You as an administrator set that tone.

We can do better in education. I know we can – and we are showing that we are on that path. So, how will you spend your time on the best things this year? How will you challenge and support your teachers to do the same?

We know what’s worked – we see it in classrooms every day. We also know what doesn’t. And now that we know better, we can do better. We can be the best.

[Read more at Tennessee Classroom Chronicles] Read MoreThree big differences on Tennessee education heading into Dean and Lee’s final debate

While the first two debates have been polite and cordial between Democrat Karl Dean and Republican Bill Lee, sharp differences are emerging on hot-button education issues in the race to be Tennessee’s next governor.

The successor to Republican Gov. Bill Haslam will have the chance to shape the state’s policies for K-12 public schools in significant ways. Voters have told pollsters that education will be one of their top priorities when they cast their ballots on Nov. 6.

Both candidates agree on the need to make teacher pay more competitive — and to take closer looks at the state’s troubled testing program and the state-run district for improving low-performing schools.

But as they prepare for their final televised debate on Friday evening in Nashville, the candidates clearly don’t agree on three significant issues. The positions are based on what Dean, a lawyer and former mayor of Nashville, and Lee, a businessman and farmer from Williamson County, have said during their first two faceoffs, as well as on candidate surveys.

1. Using public dollars for private schools

The use of taxpayer-funded vouchers to pay for private school tuition has been debated for more than a decade in the legislature, but such proposals have been consistently fended off by a bipartisan coalition of Democrats and rural Republicans.

The current governor said he’d sign voucher legislation if lawmakers passed it, but they never did and he didn’t champion the policy shift as research showed mixed results on the impact of vouchers on students.

That climate could change if Lee becomes governor. A graduate of public schools who sent his children to a mix of public, private, and home schools, the Republican nominee has praised policies that give parents more school choices for their kids. Lee has said that vouchers have potential, but he has sidestepped specific questions about such programs.

Dean has seized on the voucher issue as a pivotal difference between him and his opponent and this week released a TV ad suggesting that the policy would undermine public education.

“Funding has always been an issue, but we should do nothing to take away from the strength of public education,” Dean said during their second debate in Kingsport.

He went on to talk about his support for nonprofit charter schools as mayor of Nashville from 2007 to 2015, but characterized vouchers as a different animal altogether.

“I have the scars on my back from my work in education reform,” Dean said, “but I do not believe in vouchers because vouchers actually take public dollars and put them into a private education system.”

2. Expanding early childhood education access

Both candidates want to improve the quality of publicly funded preschool programs across Tennessee, but have a different timetable for expanding access beyond the state’s lower-income families.

Dean advocates for universal pre-K programs, while Lee is cool to that idea.

“I’m always the guy who believes that government is not the answer,” Lee said during their first debate in Memphis.

Dean said investing more dollars in early childhood education makes sense if education is the No. 1 priority in a state that wants to prepare all children for success in the classroom and ultimately the future of work.

“That would be something that I would try to fund as quickly as I could,” Dean said of universal pre-K.

But Lee says that approach is premature in light of a landmark five-year studyreleased in 2015 by Vanderbilt University. Researchers found that, while helpful in the early years, participating in the state’s public programs could actually negatively impact students as they advance through school — a shocking finding that ignited new efforts to step up pre-K quality across Tennessee.

“I believe we owe it to taxpayers and parents to focus first on how we can improve quality to ensure that any gains are sustainable,” Lee told Chalkbeat earlier this year. “That begins by working with our state universities and colleges of education to ensure they are driving quality training for early childhood educators, while at the same time working with local education agencies to set goals for improvement and identify best practices across the state.”

3. Arming educators in schools

A proposal to give some teachers handguns and train them on firearms fizzled this year in the legislature under opposition from the current governor, who instead spearheaded additional investments in school security.

But Lee, who has been endorsed by Haslam, thinks that arming teachers could help prevent mass school shootings like the one that killed 17 people in Parkland, Florida, last February.

“We protect our banks with guns, we protect our judges, we even protect our governor. But we leave our children defenseless in gun-free zones,” Lee says on his campaign website. “We should absolutely allow a qualified and vetted teacher to make the choice to be a part of the solution.”

Dean believes that arming teachers would be a big mistake.

“Putting guns in the classroom would create more problems and concerns,” said the former public defender. “The common sense approach would be to provide school districts with the resources they need for trained law enforcement and school resource officers. Of the hundreds of educators I’ve met during his time as mayor and on the campaign trail, the overwhelming consensus is that teachers want to teach. They do not want to be armed.”

With less than a month to go until Election Day, polls show Lee with a solid lead over Dean in a state that leans mostly Republican.

The third debate is taking place on the campus of Belmont University and will be broadcast live beginning at 7 p.m. Central Time on Nexstar Media Group affiliates statewide.

[Read more at Chalkbeat] Read MoreThe Little College Where Tuition Is Free and Every Student Is Given a Job

There’s a small burst of air that explodes from every clap. And when hundreds of people are clapping in unison, it begins to feel like a breeze—one that was pulsing through the Phelps Stokes Chapel at Berea College in Kentucky. The students and staff that had gathered here were stomping, clapping, and singing along, as they were led in a rendition of the Civil Rights era anthem, “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around.”

They had packed into the wood-framed building for a convocation address, where the speaker, Diane White-Clayton, would be talking about “Jesus, the Ultimate Rebel with a Cause.” Berea does not have a sectarian affiliation, but the remnants of its Christian foundation are readily apparent—so much so that, as Alicestyne Turley, a history professor at the college, told me, “we have students who come here who think they’re coming to a Christian college,” à la Liberty University or Notre Dame.

White’s address was dotted with the markings of a Sunday sermon—not the stuffy kind, but the kind I’d heard time and again growing up—the jokes, the whooping, the lessons that come in threes. In her speech, White explained to the students that it didn’t take supernatural abilities to do great things—only a purpose—and that all the evidence they needed could be found on the campus where they stood.

Berea College isn’t like most other colleges. It was founded in 1855 by a Presbyterian minister who was an abolitionist. It was the first integrated, co-educational college in the South. And it has not charged students tuition since 1892. Every student on campus works, and its labor program is like work-study on steroids. The work includes everyday tasks such as janitorial services, but older students are often assigned jobs aligned to their academic program, and work on things such as web production or managing volunteer programs. And students receive a physical check for their labor that can go toward housing and living expenses. Forty-five percent of graduates have no debt, and the ones who do have an average of less than $7,000 in debt, according to Luke Hodson, the college’s director of admissions.

On top of all of that: More than 90 percent of Berea College students are eligible to receive the Pell Grant—often used as a proxy for low-income enrollment. Most of those students, 70 percent to be exact, are from Appalachia—where nearly one of every five people live below the poverty line. And that recruiting pipeline in Appalachia produces a rather diverse class—more than 40 percent of the student body identify as racial minorities.

Every couple of years, Berea College makes national news, often for its tuition-free promise—a promise that has become all the more noteworthy as the national student debt crisis has grown. But late last year, Berea College made headlines for a different reason: a provision in the Republican-led tax reform effort that would have charged colleges with large endowments a 1.4 percent tax on the investment earnings from their endowments.

Berea has a $1.2 billion endowment—which is how it can afford to cover the tuition of every student—and the school estimated that the tax would cost it upwards of a million dollars a year, effectively forcing it to cut back on the number of students admitted. The rebuke came quickly from both sides of the aisle. Democrats argued that it was an example of Republican mismanagement of the entire tax debate, and Republicans painted the debacle as Democrats holding a worthy college hostage. It was a point of order raised by Senator Bernie Sanders, Republicans argued, that prevented Berea from being exempt from the tax in the initial bill. Higher education leaders—even notable Republicans such as the Bush-era education secretary Margaret Spellings—were skeptical of the tax. The tax’s goal was ostensibly to punish colleges for amassing large endowments as the cost of college was rising, and not evenly helping students. By ensnaring Berea, a college that charged no tuition because it has such a large endowment, the logic of the tax broke down.

Ultimately, through a mix of righteous indignation and friends in high places, including Kentucky Senator Mitch McConnell, language was added to the bill saying that a school needs to have 500 “tuition-paying” students to qualify for the tax. That exempted Berea, where no students pay tuition. But the dust-up did raise an interesting question. If Berea can do so much with a $1.2 billion endowment, why can’t the Harvards of the world do the same with their billion-dollar endowments? The answer lies in Berea’s unique history.

erea college had been around for less than a decade when its founder was run out of town.

John G. Fee, a minister and abolitionist, opened Berea in 1855 on land provided by Cassius Clay—the son of Kentucky’s largest slaveholder—who also happened to be an abolitionist, though one who favored gradual emancipation. The school has a simple motto: “God has made of one blood all the peoples of the earth.” The education of those people, Fee believed, should reflect that.

Needless to say, Fee’s belief in interracial education rubbed the slaveholders in Kentucky the wrong way. In 1859, national tensions over the direction of the country—whether slavery was the future or not—began to boil over. More than 60 armed white men attacked Berea, telling the abolitionist families that they had 10 days to leave the state, or they would be killed. Fee and his family—ardent abolitionists themselves—were among those who left.

So, with his family, Fee fled to Ohio, and the college was forced to cease operation. The winter weather made for a difficult exodus, and his youngest son died from diphtheria. The family carried the young boy’s body back to Kentucky where he was buried. Fee would later write that the ordeal strengthened his, “purpose to return, and my claim upon this, my native soil and field of labor.” But perhaps it strengthened his wife Matilda’s resolve more. During the Civil War, Matilda returned to Berea. John, not to be left behind, followed at the war’s end.

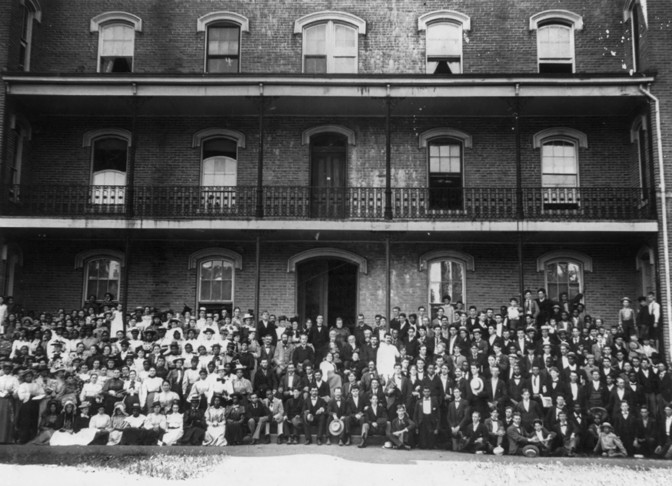

But Fee didn’t come back to Berea alone. He had been devoting the lion’s share of his time to educating—and preaching to—recently freed black people at Camp Nelson, in Kentucky, near the end of the war. He brought dozens of those people with him to reopen Berea College after the war. In the late 1800s, the student body was roughly half white and half black. In 1889, for example, there were 177 black students and 157 white. And all of the students worked on the campus grounds. That had been a central tenet of the college from the beginning. Work, Fee believed, was the great equalizer.

As the school grew, it officially became tuition-free. A new president, William Frost, whose family housed enslaved people who fled captivity during the war, published an advertisement toward the end of the 19th century boasting that the college had “29 teachers and 12 buildings,” that it was endorsed by “Christian Bodies of every name,” and, most importantly, that “Tuition is Free!”

The ad undoubtedly caught the eye of several students, including, potentially, Carter G. Woodson, a plucky young black man who enrolled at Berea in 1897, and a historian who would go on to be known as the “father of black history.” But at the same time, Berea’s interracial education made a lot of Kentuckians uncomfortable. Most notable was Carl Day, a Kentucky legislator, who, lore has it, was taking a train through Berea when he saw two young women—one white, one black—embracing each other. Day introduced a bill in the Kentucky House of Representatives on January 12, 1904, that would prohibit white students from attending school with black students. Schools found to be in violation of that law would be forced to pay a $1,000 fine for each day they were in violation of the law — and teachers could be fined $100 a day. Berea was the only integrated college in Kentucky at the time.

The Day Law, as it came to be known, was passed in 1904, and the college tried to find a way around it. It considered opening an auxiliary campus, but the law expressly prohibited colleges from operating an integrated campus within 25 miles of their main campuses. They sued, but Kentucky’s high court agreed that the law was necessary to prevent interracial marriage and racial violence. And the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the state’s ruling, citing its decision in Plessy v. Ferguson that it was within a state’s rights to prohibit integration. Only one Supreme Court justice dissented: John Marshall Harlan, a native Kentuckian, who had also dissented in the Plessy case. “Have we become so inoculated with prejudice of race,” Harlan wrote in his dissent, “that an American Government, professedly based on the principles of freedom, and charged with the protection of all citizens alike, can make distinctions between such citizens in the matter of their voluntary meeting for innocent purposes simply because of their respective races?” Loretta Reynolds, dean of the chapel at Berea, perhaps put it best: “It was a sinister law.”

After the Day Law took effect, the college paid for the black students who had been enrolled but had not completed their degree programs to attend historically black colleges and universities. And it split its endowment to open the Lincoln Institute for black students in Simpsonville, Kentucky. But little by little, year by year, students, faculty, and staff began to forget the institution’s history and commitment to interracial education. In some ways, that forgetting was intentional. The college was struggling financially—most of its money had dried up—and it needed to find something that people would support, Turley told me, “and what people would support was the education of poor whites.”

The prospect of educating poor white people from Appalachia for no tuition was something that the community could get behind. And nearly 100 years ago, on October 20, 1920, the board made sure that the college would be able to do so for a long time. According to Jeff Amburgey, the school’s chief financial officer, “The board essentially said, for Berea to sustain its funding model,” any unrestricted bequests—essentially money that someone leaves the institution after they have passed away, that is not tagged for a specific purpose—could not be spent right away. Instead, he says, the money was expected to be treated as part of the endowment, and only the return on that investment could be spent.

The college has followed that policy ever since. In fact, as Amburgey told me, “46 percent of our endowment, as of June 30, 2018, is what we call quasi-endowment, so, roughly $500 million is the current market value of those unrestricted bequests” since 1920.

But as the college was rebuilding its finances, there were no black students. Between 1904 and 1950, the Day Law prohibited black students from attending the college. In 1950, however, the law was amended to allow voluntary integration above the high school level. Two black students, William Ballew and Elizabeth Denney, enrolled that year. And in 1954, the year the Supreme Court ruled segregated schools unconstitutional in Brown v. Board, Jessie Zander became the first black graduate of the college since the Day Law took effect.

The reintegration of the campus was difficult. “The community was gone,” Turley told me. There were still the black people who worked for the school, and lived in the community, but the community of students and faculty had been decimated by the law. The school had to relearn the philosophy of its founder, John Fee, slowly, but surely. Six or seven black students came back in the ’50s. A few more in the ’60s. And, by the ’70s, black students made up roughly 6 percent of the student population.

Each year, the school has built on those numbers, and now black students make up 27 percent, Latino students 11 percent, and international students—who are required to be low-income by the standards of their own countries—make up another 7 percent. Several people who I spoke with lamented that the numbers sound good, but they’re nowhere close to the 50-50 enrollment Berea once had. However, they’re doing far better than a lot of similarly situated liberal-arts institutions. And it’s tuition-free—something that states are struggling to achieve for their public colleges. It seems like as close to an ideal system for low-income higher education as is possible, but school officials worry it may not last forever.

eff amburgey spends a lot of time thinking about the worst-case scenario. The endowment is what keeps the lights on—literally. About 75 percent of Berea’s operating budget comes from endowment investment earnings—the spendable return on the endowment. Another 10 percent of the budget is from charitable giving, another 10 percent is from federal and state grants such as Pell, and then there is other, extraneous income making up the other five percent. The school pays the tuition, $39,400 per student a year, internally.

But having an endowment pay for most of a college’s expenses rather than, say, tuition, can be a recipe for gambler’s ruin. As Lyle Roelofs, Berea’s president, told me, “we’re not the kind of institution that holds the world of finance in disdain. We are dependent on it.” If the stock market were to dip—lowering the endowment’s return on investment—the college might have to reconsider its tuition promise.

The college has been tested before. In the 1970s, Willis Weatherford Jr., the president at the time, broached the idea of charging tuition as the financial markets went sideways during Vietnam. But the college started accepting federal funds instead—things such as Pell Grants. Following September 11th, the prospect of charging tuition was raised again, and again in 2008 to 2009 when the recession hit. Every time they decided against it. Each of these financial downturns hit the school hard, says Amburgey, but they aren’t close to the the worst of the possibilities he’s considered.

The worst thing that could happen to Berea, Amburgey says, would be a financial market that went down—triggering less than 5 percent returns on their endowment each year (roughly the amount they spend each year to keep the place running)—and stayed that way for a long time. Imagine the worst part of the 2009 financial crisis lasting for a decade. The college has mechanisms built in to help sustain it in such an event. In the 1990s, for example, when the college had a 39 percent return on its investment one year, they stashed money away in a sort of rainy-day fund. But rainy-day funds are useless in a flood.

Berea’s system seems like a solution for the ballooning prices that plague students at many U.S. colleges, but it’s also something that would be incredibly hard to replicate for most institutions. Berea has been building this model for more than a century—if another college were to switch to this model without an existing financial cushion, a recession could essentially close their institution.

But it’s possible colleges could start by emulating certain elements of the Berea model. Paul Quinn College, a historically black college in Dallas, recently started employing its students on campus, and joined the work-college consortium, a group of federally designated work colleges, in 2017. The institution, which once feared closure, has now announced the opening of a second campus.

But going tuition-free is a bigger ask. Berea College enrolls between 1,600 and 1,700 students in any given year, so scaling a tuition promise like theirs would be a much heavier lift for public regional colleges, and even larger private colleges. It would be theoretically doable, though, for some highly selective colleges with massive endowments. Some of them, such as Princeton, Brown, and Cornell, have already eliminated tuition for low-income students. But endowments are not like bank accounts where all of, say, Harvard’s $37 billion can accessed instantly—often some of those funds are earmarked for specific things such as a professorship, or a program, or a specific scholarship. Colleges can not legally break that agreement.

Berea largely owes its success today to the board’s decision, roughly 100 years ago, to make sure there would be endowment funds to spend on students. And to the decades of leaders since who have kept that commitment.

The energy that pulsed through the wooden risers in the Phelps Stokes Chapel was palpable as the students sang. “Just march,” Diane White-Clayton told them, “because some of y’all aren’t singing.” The students laughed, as they stopped singing and clapping and simply stomped. “I want you all to leave here with the determination that nothing,” she exclaimed, “is going to turn you around!”

Higher education in America is plagued by many problems: limited access for low-income and minority students, affordability, etc.—but Berea is different than much of the rest of higher education. But those differences make it fragile. It’s unclear if its model will last forever, but for now, it has a simple purpose. It wants to keep education tuition-free for its students for as long as possible.

“Alright, give me back that bass line,” Clayton told them as the students began clapping again.

“I’m gonna keep on walkin’,” they bellowed, “keep on talkin’. Marching to my destiny.”

[Read more at The Atlantic]How We Prepare Future Educators of Tennessee

By Lillian Hartgrove, Chair of the Tennessee State Board of Education

A better Tennessee starts with strong teachers.

Teachers impact every other profession in our state by developing people — equipping students with the critical knowledge, tools, and skills they need to succeed in post-secondary education, careers and beyond. Now more than ever, it is imperative that we have the finest teachers in Tennessee’s classrooms.

Tennessee seeks to enter the top half of all states on student outcomes by 2020, so we must continue to implement the highest academic standards and commit to our mission of providing quality education to all students. By employing the best and the brightest teachers, we can better ensure we are truly preparing the children of Tennessee for success after high school.

But our state, like the nation, faces a challenge in attracting enough students to the profession of teaching. There is a teacher shortage across the country, and it is crucial that we in Tennessee find solutions collectively and in collaboration with each other. The State Board of Education is committed to establishing and maintaining policies intended to help build and strengthen pipelines of high-caliber educators. Similarly, educator preparation providers, current educators, and our communities across the state can and are playing big roles in recruiting, developing, and training a strong teacher workforce.

Education preparation providers (EPPs) refer to the programs at more than 40 colleges, universities, and alternative certification pathways around the state that attract, enroll, prepare, and graduate the students who will become highly effective teachers. The State Board of Education ensures high academic standards for these programs, and since EPPs deliver the first professional training to future teachers, they have a great responsibility and are critical partners in this work.

However, due to the teacher shortage, enrollment has markedly declined in EPPs. Earlier this year, the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education reported that from 2007 to 2016, there was a 23 percent decline in the number of teacher preparation program completers across the United States. To get more highly effective educators into our classrooms across the state, we must do more, earlier, to encourage more students to pursue a career in teaching.

Now is the time to shine a brighter light on the education profession as a gratifying career opportunity for students and high school seniors who are considering their next steps.

Teachers, school, and district leaders have a huge part to play in inspiring our future educators. We need more teachers in diverse subjects, grades, and communities. Teachers who talk to their students about their careers and do their best in the classroom each day are excellent role models for our students, and for the profession itself.

Every Tennessean can play a role by recognizing the merit of the teaching profession and encouraging more students to become an educator. Valuing the profession comes in many forms. Parents, family members, coaches, and community members who are interacting with students can share stories of the teachers who inspired them, and demonstrate respect and support for the teachers in a student’s life.

Strong educator preparation programs, and more and more Tennesseans helping encourage students to pursue this rewarding career, will shape the education landscape of our great state for years to come.

We will make Tennessee an even better state for teachers and students alike by putting the best and brightest educators in every classroom and rewarding teachers for their contributions to our society. We can do this if we all work together. Let’s do it for our future generations and for the future of Tennessee.

[Read more at Tennessee State Board of Education] Read MoreTennessee’s evaluation system is a model for the nation

A new report out today reinforces what many other researchers have found to be true: Tennessee’s teachers are improving more (and more rapidly) each year as a result of our teacher evaluation model and support.

Today, Tennessee is called out as a model for the country in a report by the National Council of Teacher Quality, following a similar report last week from FutureEd at Georgetown and a report earlier this year from the Tennessee Education Research Alliance. These independent analyses provide several key takeaways about our approach to teacher evaluation, or TEAM: the Tennessee Educator Acceleration Model.

- Our evaluation model has been a key driver to our success. Tennessee teacher improvement appears to be greater in more recent years – since we transitioned to our TEAM model in 2011-12. Improvement occurred as we adopted common language and a common understanding of expectations with ongoing support for teachers.

- Our teachers keep getting better. Unlike in other states, in Tennessee, teachers continue to develop their effectiveness throughout their careers – well after their first few years in the profession.

- Our best teachers are staying. The TEAM model recognizes strong teachers and keeps them in the classroom, and the teachers who have chosen to leave the profession have tended to be those who were lower rated.

- Our teachers believe evaluation is helping them to improve. The vast majority – 72% – of Tennessee teachers say our teacher evaluation model is improving their teaching, which is up from 37% just a few years ago. And by every measure, student performance under higher expectations is better now than it ever has been.

Tennessee has had a unique, targeted, and sustained approach to teacher evaluation that is different than any other state. We have focused specifically on student growth to say what happens in the classroom matters, and we have included multiple measures that we know contribute to student success. Tennessee’s evaluation model, with its continuous improvement design and focus on growth, is pushing all of us, at every level in education, to become the best teachers and leaders we can be and to make sure our educational system maximizes student success. Continuing this approach moving forward is the single most important policy we can have in place to ensure that we remain and accelerate as one of the fastest improving states in the nation.

In any measure you look at – results from the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP), ACT scores, graduation rate, Advanced Placement scores, industry credentialing, or students’ access to opportunities to prepare for college and careers – our students are doing better and have more opportunities now than they did in 2011-12. We believe that these outcomes would not have happened without the intentional focus on student progress that was underscored by the high academic expectations we set for every single student in Tennessee. And, because of our statewide approach to educator evaluation and support, we have been able to better reinforce the implementation of TEAM and align state resources and priorities around accelerating teachers’ continued professional growth. This statewide approach is pushing all of us, at every level in education, to become the best teachers and leaders we can be and to make sure our educational system maximizes student success.

As these reports note, Tennessee has led one of the most comprehensive education reform efforts in the country over the past 10 years, overhauling teacher evaluation and professional development and strengthening teacher and school leadership, while simultaneously raising expectations for students. During this same period, our state has seen steady improvement in teachers’ effectiveness and students’ achievement. This is a remarkable testament to the importance of good, bi-partisan state education policy led by Governor Bill Haslam with support from the Tennessee General Assembly. This sustained focus on evaluating and supporting teachers continues to improve the profession and more importantly, the futures of our students.

As these reports note, Tennessee has led one of the most comprehensive education reform efforts in the country over the past 10 years, overhauling teacher evaluation and professional development and strengthening teacher and school leadership, while simultaneously raising expectations for students. During this same period, our state has seen steady improvement in teachers’ effectiveness and students’ achievement. This is a remarkable testament to the importance of good, bi-partisan state education policy led by Governor Bill Haslam with support from the Tennessee General Assembly. This sustained focus on evaluating and supporting teachers continues to improve the profession and more importantly, the futures of our students.

As I noted in my comments at the LEAD 2018 conference last week, our state’s laser focus on what happens in the classroom – the results of teaching and learning between each student and teacher – and the expectations and supports set by leaders at all levels continues to be why Tennessee is moving from good to better to best. Today’s report highlighting teacher evaluation simply put another exclamation on that point and remind us that we continue to be on the right track. Now, let’s keep going.

[Read more at Classroom Chronicles] Read MoreTennessee needs to better prepare students before third grade | Opinion

In the last decade, Tennessee’s education reforms have driven historic improvements, resulting in high academic standards, aligned assessments and accelerated growth in academic achievement for students in grades 3 through 12.

Despite the improvements, student proficiency still falls short of Tennessee’s goals. Tennessee’s standards-aligned assessments reveal alarming news: a majority of Tennessee’s students in third to 12th grades are not proficient in English and math.

The Nation’s Report Card tells a similar story. Despite Tennessee’s improvements, proficiency rates still rank it in the bottom half of all states.

Especially striking is that by third and fourth grades, our students are already significantly behind, with nearly two-thirds not proficient in English and math.

We know that when students are not proficient by third grade, they are four times more likely to drop out of high school and 60 percent less likely to pursue a post-secondary degree. Once students fall behind in third grade, they tend to stay behind or fall further.

Low proficiency in third grade is a clear indication that the quality of children’s learning prior to third grade requires significant improvements.

Learning begins at birth. The brain develops more in the first five years than at any other time during a person’s life. Deficits in early literacy and math skills have been documented as early as nine months and widening from there along family income lines. Early literacy, math and early social skills at kindergarten entry are strong predictors of future academic success.

Bipartisan commitment to literacy and early childhood education

Tennesseans for Quality Early Education (TQEE) is committed to improving early education to ensure stronger academic achievement for all students and shared prosperity in Tennessee. We are a bipartisan group of people and organizations in business, nonprofit, education, healthcare, law enforcement and faith communities advocating to make high-quality early education, from birth through third grade, a state priority.

Our policy priorities, available in more detail at www.tqee.org, include:

Engaged and empowered parents. Parents are children’s first and most influential teachers. We advocate for policies that engage and empower parents through evidence-based home visiting programs, parent-teacher partnerships in childcare and elementary schools and school-community partnerships that expand families’ access to local resources.

High quality, affordable child care. High quality, affordable child care is critical to support the more than 300,000 young children in Tennessee with working parents. Child care directly impacts current and future workforce development, as well as family economic stability.

We back policies that set high standards for teaching, learning and outcomes, recruit and retain high quality teachers, and anchor state reimbursement rates to actual cost of quality.

Excellent early grades teaching. To boost student outcomes in third grade and beyond, instruction from pre-kindergarten to third grade must be better aligned with best practices and how young children learn. We support improved instructional materials, investments in training for early grades teachers and principals, and accountability for results.

Stronger accountability and continuous improvement in early education. Tennessee has limited statewide data on early learning from birth to second grade. To maximize investments in public education, Tennessee should commit to a birth-to-5 early learning data system, developmentally-appropriate methods to measure and improve instructional effectiveness pre-k to second grade and better support for early grades teachers to use student data to improve learning outcomes.

Eighty-one percent of Tennesseans support “major change” in public education, and 69 percent say they would vote for policymakers who support early education, according to a statewide survey conducted by TQEE.

Tennesseans want better education outcomes and understand that depends on giving our children a smart start. TQEE stands ready to work with the next governor and General Assembly to make early childhood education the starting place for transformational change.

Tara Scarlett is president and chief executive officer of Scarlett Family Foundation and board member of Tennesseans for Quality Early Education.

[Read more at The Tennessean]At this KIPP high school, a new tactic for getting students to college: bringing college to them

It’s common for high school students to head to college campuses for classes. It’s much rarer for a college to set up shop on a high school campus.

But that is what’s happening at a KIPP high school in New Orleans this year. Bard College, a New York-based private liberal arts college, is enrolling half of KIPP Renaissance’s juniors in a two-year program designed to end with them earning both a high school diploma and an associate’s degree.

It’s a new tactic in the national charter network’s push to get its students to and through college: combining the start of college with high school in a way that makes higher education feel attainable — even unavoidable.

“This partnership helps us not just kind of guess what it would take getting kids to get into college,” said Towana Pierre-Floyd, the principal at KIPP Renaissance, which held a ceremony Tuesday for students entering the program. “Working with Bard [helps us] see how it actually would shake out for students when they start taking college courses full-time and have to navigate time management and rigor in different ways.”

Early college programs, which can cut down on the time and money needed to earn a degree and expose students to the style and pace of college work, are growing in popularity as an option to help students from low-income families and communities of color.

Most of those programs, though, have students earn credits at community colleges during part of the school day. The KIPP-Bard partnership is unique because it’s full-time, housed completely on a high school campus, and operating in conjunction with a charter school. (Bard operates several of its own early-college high schools across the country, but none inside other schools.)

KIPP’s program will work by enrolling students who have completed the majority of their Louisiana high school requirements at the end of sophomore year, school officials said. (The other half of KIPP’s students will follow a different academic program.) Ten Bard staffers, including six professors — some from Bard, others hired locally — will teach courses on KIPP’s campus.

“Bard is not hurting for applicants,” said Stephen Tremaine, the college’s vice president of early colleges. “For Bard, the upside is that the way that higher education in America identifies and searches for talent is incredibly criminally limited to one kind of student that’s one age and often in one neighborhood. We think that colleges miss out on real talent by not being willing to open that up.”

Douglas Lauen, a public policy professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who co-authored a study examining early college high schools, estimates about 300 early college campuses dot the country, with 80 alone in North Carolina. He says the model gained steam in the state after an injection of money from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, supplemented by public funding. (The Gates Foundation is also a supporter of Chalkbeat.)

A small but growing base of research has found the model generally helps students from low-income families — increasing high school graduation rates, boosting associates degree completion rates, and raising four-year-college enrollment, one study out of North Carolina found, though that college enrollment increase was at less selective schools.

“There appears to be a causal effect” of the program on a student’s chances of making it to and through college, said Lauen.

Adding college classes to high school is still a tricky proposition. Some have raised questions about the value of the associate’s degree students leave with and about whether the the courses students take in early-college programs are truly at a college level.

“We have to be thinking, are we giving them a credential for the sake of it, or are we giving them something useful for the job market eventually?” said Nathan Barrett, Lauen’s co-author. Barrett is now an associate director at the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans at Tulane University, about seven miles from KIPP Renaissance.

Still, Barrett and Lauen see real benefits. An associate’s degree can keep students on the path to a higher-level degree, helping them avoid the cost of some college credits. KIPP officials also said they hope the program gives students the confidence to apply to more selective universities than they otherwise would.

“KIPP arguably may have more structure than students will get when they go to college, so perhaps this will get them in a place where they will be pretty much ready to go in the world and persist in college and with a career,” Barrett said.

[Read more at Chalkbeat]Giving Rural Students ‘the Short Box’

SALT LAKE CITY — A student’s decision about where to apply to college can depend on what is in front of her, Jazmin Regalado said during a session at the National Association for College Admission Counseling’s recent annual meeting.

Regalado, a freshman biology and premed student at New Mexico State University, recounted her application process in high school. She is from Fort Sumner, N.M., which has about 1,000 residents and is best known as the burial site of the outlaw Billy the Kid. Growing up, her elementary, middle and high schools were all together.

One counselor is supposed to help seniors, but she didn’t have time to do it all, Regalado said. An English teacher also tried to recruit colleges and universities to come talk to students.

“There are five in the state, and out of those five, like three came, and there was one from Texas that came,” Regalado said.

She had wanted to attend the University of Chicago, but the application was long, and she never finished it. She ended up sticking with the institutions that visited her school.

“Being from a small town, you only know so many colleges,” she said. “You have tunnel vision.”

Regalado spoke alongside several professionals involved in college admissions in a session about outreach to rural students. It’s a topic of interest at many colleges and universities as leaders continue to grapple with polling showing deep skepticism of higher ed from Republicans, and as a rural-urban divide contributes to the country’s political schisms.

Panelists didn’t address the politics of recruiting rural students. But they did make the case that those students can be very different from what admissions officers picture.

“Think specifically about the types of rural students that you’re looking to recruit to colleges, because rurality is different everywhere,” said Jennifer Carroll, professional learning lead at Kentucky Valley Educational Cooperative.

For example, industry and agriculture don’t have meaningful presences in Carroll’s region of southeastern Kentucky. Tobacco was a major crop, but it disappeared because of government action. School systems are the largest employers. Students can’t model their careers on local businesses, because those businesses aren’t around.

Further, students don’t have money to spend on college applications or standardized tests. They likely take a standardized test once, when schools pay for them to take the ACT. Some students don’t have running water at home.

It’s a very different rural environment than one with, say, a large agricultural presence or energy industry. Carroll’s message wasn’t that some rural areas are better than others — it’s to remember how different they can be.

Beyond that, many students simply aren’t familiar with college campuses. The food is different. Attitudes are different. Norms are different.

“Our rural students, unless they are students who are kind of coached at home by parents or folks who have been in a college setting, they don’t ask for help,” Carroll said. “That is just one of those cultural things about kids from our area.”

High school counselors are facing challenges, too. In rural areas, they often have an inhuman number of responsibilities.

They can be responsible for scheduling, lunchroom duty, releasing buses, and social and emotional counseling, said Megan Dorton, senior associate director of admissions at Purdue University. Then at the end of the day, they have to find time to help a student sign up for the SAT or ACT.

Purdue, Indiana University in Bloomington and the College Board have a partnership called Making College Connections, which attempts to help high school students understand postsecondary options and prepare to apply to college.

They came up with the idea of a college planning night, selecting rural high schools in far-flung regions of the state and partnering with school counselors. They offered to help with SAT preparation and college planning if those services were in need.

“We have some resources and we have some tools, and so how can we use these to reach students that are really important to us?” Dorton said.

Purdue has made a point of showing up at high schools. Its representatives have visited all of the nearly 400 high schools in Indiana at least once every other year. It visited most schools every year.

“That’s not solving the problem, but it was low-hanging fruit to us, and we’re working on ways to evolve,” Dorton said.

Another panelist stressed that it is important to build bridges between colleges and rural communities that aren’t directly related to recruiting students to a college campus. Colleges need to be engaged in communities in ways that are responsive to their needs, said Rachel Fried, program coordinator at GEAR UP, a federally funded college access program at Appalachian State University in North Carolina.

“Folks start to see that universities aren’t on a hill, that they are there to help, not just to take kids to college, but really to support the surrounding area,” Fried said.

When it comes to recruiting rural students, many colleges are likely doing it the wrong way.

Too often, colleges think they can reach rural students virtually, Fried said. They know they can’t visit every place, so they go to urban centers and expect to connect with rural students over the internet.

But many Appalachian communities don’t have widespread internet infrastructure. Fried often hears someone say that isn’t a problem because everyone has smartphones. That’s not true, though. And even if it were, many students don’t have cellphone service at home.

“I would posit that colleges and universities suggesting virtual opportunities as the solution to rural education equity is actually giving the short kid the short box,” she said. “Maybe you do your virtual stuff with your urban schools that have tons of technology, that have videoconferencing, whatever, and you actually go visit places that don’t have that type of infrastructure.”

The messages students hear also matter. Students from Appalachia might go to college so that they can come back and “help their own,” Fried said. Are colleges thinking about messaging that shows the type of learning students can use if they return home?

Jeff Carlson told a similar story. He is senior director for strategy, operations and rural engagement at College Board and moderated the panel.

He talked about advertisements that showed a child from the Rio Grande Valley area who fell in love with art history because of Advanced Placement courses. The student enrolled in New York University and went on to hold a high-profile job in New York City.

“Wasn’t that great?” Carlson said. “Not for that kid’s family in the Rio Grande Valley. Not for that kid’s teachers. The biggest fear is that you’re going to put a ton of investment into this kid, you’re going to watch them grow up, and they’re going to run away to an urban area and never come back.”

Not coming back might be the best thing for some students, and it might be what some families want, Carlson said. But if admissions officers only think about their institutions plucking students out of town never to return home, they are sending the wrong message.

Carlson, who grew up in an 800-person town located three hours north of Boise, Idaho, also talked about rural resentment — a belief, perception or sense that rural areas are ignored by decision makers. The perception is that rural areas don’t always get their fair share, and that rural areas have distinct values and lifestyles that are fundamentally misunderstood, he said.

Yet rural areas are a significant part of the country. Half of U.S. school districts — 7,000 out of about 14,000 — are rural, Carlson said. One out of every three students grows up in a school district serving an area with a population of less than 50,000 people. About one out of every five grows up in schools located outside of areas with population centers of at least 2,500 residents.

Panelists suggested other ways to connect to rural students. Can a student be shown broader applications for their interests, or connections to other fields of study? A student interested in agriculture, for example, might also find a love for environmental sciences.

They also suggested asking students who go on to college to come back and speak at family nights about their experiences. On the question of coming back home after college, can families be introduced to the idea that a college-educated person might be able to live in his or her home region but work elsewhere — either working remotely or commuting? Or can they be shown certain jobs in their home communities that require college education that they never realized existed?

Connecting to rural communities can’t be done overnight, said Fried, of Appalachian State.

“When universities really decide to commit to developing rural pipelines, they are committing to a multiyear engagement process that will not yield results for the first three to five years,” she said. “We must get into communities and help and change the perception of our universities in those spaces.”

[Read more at Inside Higher Ed] Read MoreAs Tennessee Voters Prepare to Elect New Governor, a ‘Pivotal Moment’ for State’s Bipartisan Reforms on School Standards, Teacher Quality, Turnarounds

Few states have embraced education reform with the vigor of Tennessee, where leaders have instituted tough standards, rigorous tests tied to teacher evaluations, and state takeover of failing schools.

Those efforts — conducted under both Republican and Democratic governors for the past 16 years — have made Tennessee schools among the fastest-growing, as judged by scores on national benchmark exams. Now, a new leader will be in charge of that reform effort as it enters its second decade, facing problems with testing and turnaround of low-performing schools.

“We see the moment we’re in right now as pivotal to determining whether the progress that the state has made is not only going to continue but accelerate. Anytime you have transitions like this, it’s easy to go in a totally different direction or focus on other priorities,” David Mansouri, president of Tennessee SCORE, an education reform advocacy group, told The 74.

The men vying to take over stewardship of that progress are Bill Lee, a first-time candidate and the wealthy owner of a family heating and plumbing business who unexpectedly beat better-known candidates to win the Republican primary, and former Nashville mayor Karl Dean, the Democratic nominee. Current governor Bill Haslam, a Republican, is term-limited.

Most polls have Lee up by double digits over Dean, and independent election handicappers generally rate the race a “likely” Republican win.

Education has been one of the major issues in the campaign, experts said, and a poll by SCORE found it was top of mind for one-third of voters. Similar numbers of those polled cited the economy, jobs, and health care as their most pressing concerns.

The gubernatorial race so far has been polite, particularly as compared to a U.S. Senate campaign in the state, and education reform, with its bipartisan backing, hasn’t been the flashpoint issue in Tennessee that it has been in other places, experts said.

“Education and jobs have really been probably the top issues, and [both candidates] sound a lot alike, really, on that issue,” Kent Syler, a political science professor at Middle Tennessee State University, told The 74.

Both support charter schools, for instance, though Dean’s website is clear that he supports only nonprofit charters (for-profit charters are banned in the state) and is skeptical that they work in rural areas.

They both think Tennessee teachers should be paid more, and they’ve called for improved career and technical education in campaign ads.

Lee’s, for instance, shows him welding and touting his company’s history of training workers.

“I don’t just talk about vocational training, we’ve actually done it … We’re going to do that all over Tennessee,” he says in the ad.

Dean, for his part, in his own ad lists “skills training for every student” as among several big ideas he’d bring to the governor’s mansion.

The candidates’ sharpest differences on education so far have come over private school choice and school funding, currently tied up in a court case brought by three of the state’s largest school districts.

On funding, Dean says there should be increases, while Lee has called for an inspector general to weed out waste and abuse. On private school choice (which the Republican-majority Tennessee legislature has rejected several times in recent years), Dean is a firm no, while Lee backs education savings accounts, according to a candidate survey by Chalkbeat Tennessee.

“Certainly there are places where each of them wants to move and put their own perspective and stamp on the work, but I think we feel like there’s been a pretty thoughtful conversation about where we go next in education in the governor’s race and feel good about the tenor of the conversation on those issues,” Mansouri said.

Strong history of ed reform

Outgoing governor Haslam is well known in the education world, notably for his moves to create the Tennessee Promise free community college tuition program and his “Drive to 55” campaign to get 55 percent of Tennesseans to have a postsecondary credential by 2025. But Tennessee’s K-12 education reform began in earnest under former Democratic governor Phil Bredesen.

Bredesen himself is on the ballot again this year, in the toss-up Senate raceagainst Republican Rep. Marsha Blackburn to fill a seat currently held by retiring Republican Sen. Bob Corker. It’s one of a handful of seats that could determine which party controls the Senate.

Tennessee had “a little bit of a head start” in implementing some reforms when it was a first-round winner of a $500 million Race to the Top grant in 2009, Jason Grissom, associate professor of public policy and education at Vanderbilt University, told The 74.

Some of those efforts have worked better than others.

The teacher evaluation system, which awards 35 percent of a teacher’s score based on the value they add to students’ learning, as judged by test scores, is becoming more popular with educators as the years pass, said Grissom, who is also faculty director of the Tennessee Education Research Alliance, a partnership between Vanderbilt and the state education department.

Efforts to improve low-performing schools in Memphis, by giving them greater autonomy in what’s called an innovation zone, have had impressive results.