New teachers often get the students who are furthest behind — and that’s a problem for both

Being a new teacher is notoriously difficult — and schools often make it even tougher.

New research out of Los Angeles finds that teachers in their first few years end up in classrooms with more struggling students and in schools with fewer experienced colleagues, making their introduction to teaching all the more challenging.

The differences between the environments of new teachers and their more experienced teachers are generally small, but they appear to matter for both students and teachers. The tougher assignments hurt new teachers’ performance and their career trajectories — and mean that students who are the furthest behind are being taught by the least experienced educators.

It’s a long-standing issue that states and districts have struggled to address and that concerns civil rights groups.

“More than anything else in schools, teaching quality has greatest impact on student achievement and student success,” said Allison Socol of the Education Trust. “And we know that the impact of strong teachers is greater for students who are further behind academically.”

The latest study is notable in scope, looking at a decade of data on teachers in the country’s second-largest school district. The researchers compared newer teachers to teachers who had been in the classroom for six years or more, from the 2007-08 school year until 2016-17.

They found that first-year teachers served more struggling students — those who started the year with lower test scores, lower grades, and higher suspension and absence rates — than more experienced teachers. The differences were small but consistent.

Novice middle and high school teachers were also more likely to work with students learning English (7 percentage points more), students from low-income families (6 percentage points), and students with disabilities (1 percentage point). And it’s not just a first-year effect: the results generally hold for teachers in years two through five.

This isn’t simply because younger teachers work in entirely different schools. Often, novice teachers are serving more disadvantaged students than their veteran colleagues down the hall.

“One of the things we see is that the stronger teachers or the more experienced teachers are often the ones who teach the advanced classes,” said Socol, referring to research on the issue more broadly.

Teachers usually improve with experience, particularly in their first few years, so the latest results mean that students who are struggling the most are often getting the least qualified teachers.

Los Angeles Unified, responding to the fundings, said its staffers try to assign teachers fairly.

“Los Angeles Unified has counselors at schools and counseling coordinators at our six local districts who prepare master schedules that are equitable for students and built around the skills and competencies of our teachers,” Los Angeles deputy superintendent Vivian Ekchian said in a statement. “National Board Certified teachers, mentor teachers and coaches work closely with our novice teachers to support them in their career development.”

New teachers didn’t have tougher jobs by every metric. While novice elementary school teachers had slightly larger class sizes, middle and high school teachers had smaller classes (by about 1.5 students) and fewer distinct courses to prepare for than their more experienced colleagues.

But newer teachers also tended to have colleagues who had less experience and lower evaluation ratings themselves.

The researchers demonstrate that new teachers in more challenging contexts also performed worse, missed more days of school, and were more likely to leave their school. That means that new teachers’ assignments matter both in the short term — for how they perform in their classrooms — and in the long term, for whether they stay there.

Again, though, the impact was fairly small: About 20 percent of teachers departed their schools by the end of the year, and that fell by 1 point for teachers with less difficult workloads.

“Retention and support of teachers, especially novice teachers, has critical implications for school operations and, in turn, student learning and achievement,” write the researchers, Paul Bruno and Sarah Rabovsky of the University of Southern California and Katharine Strunk of Michigan State University.

The results overlap with past research showing that students from low-income families and students of color get less qualified and effective teachers, though these disparities are often modest.

Still, Socol of Education Trust said, “We know that these gaps aren’t inevitable.”

What could help? Not assigning new teachers to the most demanding classes, perhaps, and making sure they have a network of effective colleagues. Past research has suggested that better principals and more collaborative school environments can help teachers improve and encourage them to remain in the classroom.

“It’s very much about the systems of supports that we provide for those novice teachers,” said Socol.

Improving teacher preparation could help, too. Research has found that pairing student teachers with effective mentors can boost novice teachers’ skills.

Studies have shown that bonuses designed to get effective teachers to transfer intoand stay in high-needs classrooms can help reduce the share of novice teachers in those classrooms.

Many of these strategies cost money. In Los Angeles, teachers recently went on strikein part over complaints about inadequate resources.

“We should situate this in a broader conversation about about resource equity,” said Socol. “It’s really important that we equitably allocate dollars … to the schools and districts to the schools and districts that need them the most.”

[Read more at Chalkbeat] Read MoreMetro Nashville Public Schools has most students with two consecutive ineffective teachers

NASHVILLE, Tenn.–A new report from the Tennessee Comptroller’s Office finds public school students taught by ineffective teachers two years consecutively affected their performance.

TCOT conducted the study at the request of Senator Dolores Gresham. The study found over 8,000 students -1.6% of all students in the study- had a teacher with low evaluation scores in the 2013-14 and 2014-15 school years in math, English, or both subjects.

In English language arts, grade 6 to grade 7 students had the highest number and percentage of students with consecutive ineffective teachers. In math, grade 8 to grade 9 students had the highest percentage of consecutive ineffective teachers. Statewide, Algebra I students overall had the lowest access to effective teachers.

The study found the district with the highest number of students with two ineffective teachers was Metro Nashville Public Schools. The district was found to have 1,055 such students representing 2.78% of the population. Hamilton County Schools was second with 3.60% of students.

Percentage-wise, Decatur and Johnson counties led the state with 10% or more of students having two consecutive ineffective teachers.

The study found students with such teachers were less likely than their peers to be proficient or advanced on state assessment testing when students had ineffective teachers for two consecutive years.

Students who were English language learners, in special education, or in high-poverty schools were 50% more likely to have two consecutive ineffective teachers.

[Read more at Fox 17 Nashville] Read MoreRepublican Bill Haslam and DE Democrat Jack Markell, See a Bipartisan Path Forward on Schools, Standards & Prioritizing ‘Education Across the Aisle’

Can a Republican and a Democrat see eye-to-eye on education? Former Govs. Bill Haslam of Tennessee and Jack Markell found that yes, they can, during a wide-ranging one-on-one discussion titled “Education Across the Aisle.” The governors, who were brought together by the Collaborative for Student Success, covered five topics of critical importance in American education: college and career readiness, standards, testing, the current state of education and the Every Student Succeeds Act.

The Collaborative shared a transcript of the conversation with The 74, which we are presenting as a first-of-its-kind two-person 74 Interview. The transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

On college and career readiness:

Gov. Bill Haslam: When you look back, what do you see as the thing that made the most substantial difference of all the policies you put in place?

Gov. Jack Markell: I think one of the things that underlay all the policies was the fact that we were more honest with our students and parents about what it really takes these days to be successful after high school. That’s a huge deal, because for so long, people have set the bar so low when it comes to educational attainment, and we’ve got to keep raising that bar.

Haslam: We’ve had a historical issue with that in Tennessee, of not setting our expectations high enough. What did you do to change that in Delaware?

Markell: First, we went around the state, and we had conversations about stronger schools. We talked about what’s going on around the world and the fact that our students are not just competing with other students from Delaware or from the mid-Atlantic region — they’re competing with the best of the best anywhere. If they were going to compete successfully, it meant we had to have higher standards and the kind of assessments that would reflect how they’re doing.

Haslam: That was our challenge as well. The year before I came in, the United States Chamber of Commerce gave Tennessee an F for truth in advertising. We were saying that 70 percent of our kids were proficient at grade level, but when those same kids got to community college, 70 percent of them needed remedial work. There’s no way both of those things were true.

Markell: A lot of people told me it was a political mistake to have this conversation with the people of Delaware about what it really means to be proficient. But my view was, if you really explained how the world around us is changing and what those changes mean, and showed that we’ve got to act differently, that at the end of the day, it’s the right thing to do.

Haslam: How would you tell somebody to have the political courage to have those difficult conversations?

Markell: You have to know what it’s worth losing an election over. We all want to win our reelection, but sometimes if you have really tough conversations, it may not go your way at the ballot box. But my experience has been that if you’re honest with people, and if you tell them why you’re making changes, they’ll be with you. The other thing is, you have to have a sense of humility. None of us has all the answers. One of the most important things we did is we went out and listened. We asked a lot of questions of parents, teachers and people throughout the business community about what kind of future they envision for their kids and for the state.

Haslam: How did you tie in preparation for the job market in a rapidly changing world to your education vision?

Markell: This is something that everybody understands. Everybody wants their kids, when they finish high school, to be ready for college or for a career. So one of the most important things we did is we brought the business community together with the higher eds and K-12 systems. That doesn’t sound very complicated, but frankly, those conversations just had not really been taking place around the country. I think that they should. It’s really important for the businesses to take a very active role in defining the types of skills they’re going to value.

Haslam: How did you get higher ed to be nimble and reactive enough to what the businesses were telling them they needed?

Markell: We started with the community college. It’s very powerful to bring education leaders into a room with business leaders who are talking about the kinds of skills that they need, the kinds that they’re not getting today. If you ask, “How good a job are our higher institutions doing in terms of preparing young people for the future?” Education administrators, 90 percent of them say we’re doing a great job. Business leaders, 10 percent of them say we’re doing a great job.

Haslam: We built off this Tennessee promise of having said, “You can have access to higher education,” but for a lot of families, that was like, “OK, we’re going there, but where is that going to lead me?” Our community colleges are speed boats compared to the battleships of trying to turn around a four-year university. But our four-year universities are reacting as well.

I was elected in 2010. My first year, 2011, unemployment’s at 9.5, 10 percent. It was literally just about finding jobs that would come to our state. Now, it’s dramatically changed. The jobs are there, and they’re wanting to know, “Can you give me the workforce that I need?” That’s become one of my primary roles — the person standing between these businesses we’re recruiting and the community colleges, four-years and technical schools. I feel like my role is much more of a bridge now than it was when I was just out begging to get jobs.

Markell: Exactly. I’d like to be a marriage broker, because virtually every day as governor, I’d have two sets of conversations. One would be with an employer who’s saying, “I have these vacancies, but I can’t find people to fill them.” And the other set of conversations would be with individuals, maybe they were formerly incarcerated, maybe they were returning veterans, maybe they had disabilities, maybe they were youth who didn’t get the kind of education they should have gotten, saying, “All I want is a shot, and nobody’s giving me a shot.” And the fact is, with the job market being what it is today, we’ve got to do a better job of building a new pipeline of employees of talent.

Haslam: There’s talk about how divided the country is, and yet you did a nice job of working across the aisle. My sense is that the country’s not only divided, but we’re mad about how divided we are. We’re mad that the other half doesn’t think like we do. So how did you, particularly on the education issue, bridge that divide?

Markell: I thought it was very important to get out beyond the legislature to explain to the people of my state a very clear worldview: “Here’s how the world around us is changing, here’s what these changes mean for all of us and here’s what we need to do differently as a result.” For me, that worldview is very much about two massive forces at work on our economy. One is globalization, which means employers have more choices than they’ve ever had before about where to hire people. The other is technology, which means they need relatively fewer people. When it comes to education, it means we have no choice other than to invest massively in skill development. And so, even if the people disagree with the things you propose, they at least understand where you’re coming from.

On standards:

Haslam: You were there around some of the pushback around Common Core, but, like us, you were able to fight past that, set some standards that you could agree to and have some things that were more strictly identified with Delaware. How did you get that accomplished?

Markell: One thing that was helpful was we invited community leaders into our schools, where they got to sit in on actual Common Core-[aligned] lessons taught by actual teachers. As the people were leaving, they said, “Boy, that certainly seems a whole lot like a math class or an English class. That didn’t seem like some people trying to take over our government through our education system.”

Haslam: But, within that [process], obviously you’re working with the teachers who are maybe the most important piece of that. There were times when, I’m guessing, they were your partners and times when they felt like they were on the other side of the fence. How did you manage that?

Markell: I always try to be respectful, and when I had teachers say that they really did not agree with something that I was proposing, I would invite them into the office. I think it’s really important to be accessible, and for them to know that you’re listening. We really tried to make sure the focus was always on the kids. Teachers have a lot of insight about what’s in the best interest of the kids. We consulted a lot with the State Teachers of the Year. We’d get them together once a month, and I would often try to just sit in on those sessions and listen, because they had so much to add.

One thing that we also really focused on was professional development. Teachers got sick and tired of the professional development where there are 100 teachers staring at the front of the room and somebody’s talking to them. So we redesigned professional development. Every teacher in the state would sit down for 45 minutes or 90 minutes a week with a group of five peers, and they would drill into what the data was telling them about student performance.

Our states were the first two states to win Race to the Top. Part of what you were doing was defending the gains that were made, but then trying to take it to a whole other level.

Haslam: My predecessor, Gov. [Phil] Bredesen, was a different party — Democrat — but [his administration] had worked really hard to do things that I always told my Republican friends, “Hey, that’s stuff we believe in.”

They did three things, and we stuck to those. They raised the standards, what we expected every child to know. They worked really hard to get an assessment that matched those standards. And the third piece, it was very controversial and still is, they made certain the teacher’s evaluation was tied to how much the students learned during the year. It was based on a lot of things, but a piece of it was that.

Those have been the three keys in Tennessee. They were all part of our Race to the Top application. Again, people say that’s a Democratic initiative, the Race to the Top. But, I say, “No, that’s stuff we should believe in.” My job was to say, “Wait, we have made historic progress here, let’s not go back to where we were before.” We still have a long way to go, but I said, “We’ve made this great progress, let’s not go back.”

Markell: When you think about the next governor coming in, what’s your advice about how they should prioritize?

Haslam: Make certain you don’t give on your standards. We have a lot of teachers who said, “You’re expecting too much out of our kids, our kids aren’t like that.” Don’t accept that. No. 2, make sure the assessment matches, and make sure an evaluation counts what the students have learned.

On testing:

Haslam: One of the controversies around education today is, “You rely on testing so heavily, and we’re spending too much time testing our kids.” What was your response?

Markell: My response was, “Let’s be smart about the testing.” We need these high-quality assessments. But it’s possible that we’re testing too much in other places. So we provided some funding to each of our districts to do an inventory of assessments. What we really want is the assessments to be helpful to teachers, so they can identify where their students are falling behind. But that has to be paired with the right kind of professional development as well.

We had a bill that passed both houses, and that I ended up vetoing, to allow parents to opt out of these assessments. That was a tough fight. It’s easy to be against the tests — I get it. But at the same time, if we don’t have these high-quality assessments, it’s not possible for us to be honest with these students, with their parents, with the teachers, about where they’re going to go from here.

Haslam: I think that’s so well said. If we’re going to be serious about saying how much a student’s learned, then we have to have that. There are always going to be issues with it, but it’s a little like saying the scoreboard didn’t work, so we’re going to quit keeping score in high school football.

Markell: We also used a sports analogy. We used basketball, and when you set the standards low, it’s like having a basketball player practice by shooting at an 8-foot basket. They can get really great shooting at an 8-foot basket, but then they get into the game, and they’re competing against people who have been practicing on a regulation basket, and they don’t do too well. Look at where we rank compared to countries all around the world, and there’s no question that the states and the countries that do a better job of educating today are going to outcompete tomorrow.

On the current state of education:

Haslam: Now that you’re stepped back, and you look across the education scene nationally, how do you assess where we are today?

Markell: I’m worried about where we are nationally on education because I think the narrative is not going in the direction we want. I believe that the kinds of things that you did in Tennessee — setting high standards, having the courage to have the quality assessments that go with them — have to undergird everything else we do. I just think it is too easy to run away from them.

Haslam: We went through historic period in our country when we had a Republican president, George W. Bush, who set No Child Left Behind. I know people had some issues with it, but the premise was really fundamental and radical for a Republican president. They were saying, “No matter what zip code you’re in, I think you deserve the chance for a great education.” And so we started measuring achievement gaps between minority and non-minority students and looking at a lot of things we hadn’t before. All based on: Let’s measure, what does the data tell us about what that child’s actually learning? Eight years of that idea, which again, was a pretty radical transformation, I think for the better.

Then you had a Democrat president, Obama, come in and do something even more radical. As a Democrat president, he went against the teachers union, particularly on this whole idea of evaluations tied to how much students were learning. Teachers unions have traditionally been huge Democrat funders, and he went against that and said, “Outcomes matter if we’re going to have an opportunity where every child can learn.”

Those were 16 historic years in our country. I think the thing that distressed me about the 2016 election was we really didn’t have a discussion about public education. You had Bernie Sanders talking about free college for everybody, and Secretary Clinton picked up on that. But, in terms of what we need to do in public K-12 education, it was crickets out there. That concerned me.

Doing hard stuff is hard. When you put higher standards and great assessments out there, there are a lot of people that don’t want that to happen, and they can use time to erode gains.

On ESSA:

Markell: For the last couple years, the Every Student Succeeds Act has been a big part of what’s going on nationally. What are the most important things to making sure that states take fullest advantage of that law?

Haslam: You and I, we were able to make some hard decisions and say, “Well, the federal government says that we have to.” That’s gone away. Now it’s up to state and local governments. And it’s made it more important than ever that states know what direction they want to go, and then local government is the same way. Those local school board races have never been more important.

Markell: As governor, how did you interact with the local boards with respect to the Every Student Succeeds Act?

Haslam: When we were putting our plan together, every state had to get their ESSA plan approved, and our Commission of Education reached down and talked to all the different school districts to say, “Here’s what we’re thinking, here’s what the plan will look like.” Because of that, we were able to have a plan that was approved very quickly. But I don’t think you could understate that it’s a very, very different world than it was in 2011, when Race to the Top was being implemented. The federal role is dramatically minimized compared to that.

Markell: And if states do what they should, that’s going to be a good thing.

Haslam: That’s right. There’s more accountability on us than ever before.

Markell: You’ve achieved some remarkable progress in Tennessee. For states to achieve that kind of progress, the schools that are having the most difficult time have to achieve real improvements. How have you made that happen?

Haslam: We’ve had some places where we’ve succeeded and some places where we haven’t. Turning around schools is really difficult. We have a saying in our Department of Education that we’ve kind of clung to, and that’s, “All means all.” When we’re talking about “all kids,” it means all kids, regardless of zip code or disability or anything else. So we can’t accept, “Well, that’s just a historically underperforming school.”

But I think it’s really about recruiting great leaders for those schools. Having a great school is like having a great restaurant, a great hospital, a great bank, a great church or synagogue. The quality of the leader determines what that is like. And so, it’s about, “How do we go find a great leader for that school?”

Markell: It’s true. If you show me a great school, you’re also showing me a great leader.

Haslam: It’s about great leaders, ratcheting up autonomy, and ratcheting up accountability. Do those three things, and we’ll figure out the rest.

[Read more at The 74] Read More

Teach for America Nashville: Building a pipeline of teachers and leaders

Teach For America (TFA) seeks and supports an outstanding and diverse network of leaders who commit to expanding educational opportunities for all children. By recruiting high-achieving, passionate college graduates into Nashville classrooms, TFA bolsters the teacher candidate pool and builds a pipeline of local leaders to expand educational opportunity for children facing the challenges of high-need school communities.

TFA partners with Metro Nashville Public School (MNPS) and supplies nearly 70-90 teachers to the city each year. TFA and MNPS work together to combat the local teacher shortage throughout the school year and even into the summer. Through MNPS summer programs and camps, TFA teachers help students with credit recovery, remediation and enrichment opportunities.

On the 2018 Tennessee State Board of Education Teacher Preparation Report Card, TFA was one of eight teacher preparation programs to receive a top ranking.

The Scarlett Family Foundation provides funding to TFA in order to allow more students to have access to great teachers every year. With a current corps member and alumni network of 1,000 teachers and leaders in the Nashville area, TFA also cultivates a group of advocates determined to see that every child has access to a high-quality education.

Through its focus on high quality teachers, effective school leaders, equal access to summer learning, and education policy experts who are energized to advocate for all students, TFA helps Nashville students reach their fullest potential in high school, college, and beyond.

Challenging Conventional Wisdom, New Report Suggests Diversity of America’s Teaching Force Has Not Kept Pace With Population

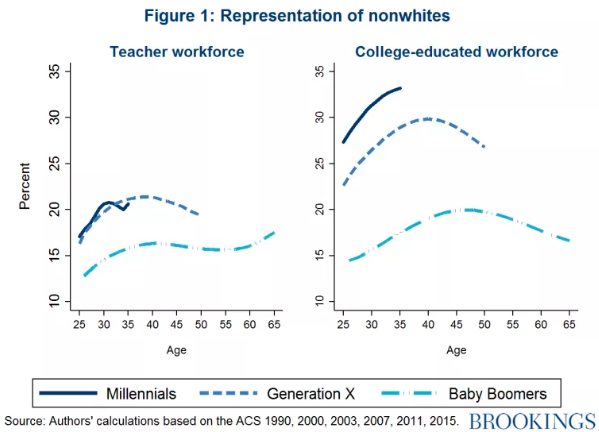

Taking aim at the perception that efforts to diversify the teaching profession are working, a new study by the Brookings Institution shows that the educator workforce is growing disproportionately white over time.

The analysis, released last week, offers a counterintuitive finding since the educator workforce has become more diverse in recent years — a fact researchers from Brookings’s Brown Center on Education Policy don’t dispute. Roughly 20 percent of educators are now nonwhite, up from roughly 12 percent in the late 1980s. But as the American population becomes increasingly diverse, the share of nonwhite teachers has failed to keep pace with the racial demographics of America’s college-educated workforce, researchers found.

Based on 25 years of Census Bureau data, researchers challenge the assertion that the profession has become more attractive to teachers of color. The finding is concerning since the diversity of teachers has failed to keep pace with the racial makeup of the students in their classrooms, said report co-author Michael Hansen, a senior fellow at Brookings and director of the Brown Center. Previous research has found that students tend to perform better in school when they have a teacher who shares their race or ethnicity.

“The biggest red flag to me, at least, is the mounting evidence on the value of having same-race teachers at least sometime within your trajectory,” he said. The latest report is part of a larger series at Brookings exploring the racial diversity of teachers. In a previous report, researchers found that racial segregation among educators is actually starker than it is for students. That’s because educators of color are typically steered to schools with high-minority student populations.

In the latest analysis, researchers found that part of the diversity problem falls on millennials. Though millennials are more racially diverse than older generations, whites make up a larger share of young teachers than they do baby boomer and Gen X educators.

It’s possible the diversity of millennial educators could grow over time. Across generations, researchers found that teachers are less diverse when they’re young but demographics shift as they age. Among older generations, teacher diversity appears to peak among educators in their late 30s and early 40s.

One possible explanation is that nonwhite groups tend to graduate from college later in life and therefore enter the teaching profession when they’re older. But the racial diversity of millennial teachers is “virtually identical” to the diversity of older generations when they were younger, researchers found.

Though the share of nonwhite educators has grown in recent years, the “increases in racial diversity are more due to the fact that Generation X and millennials in general are more diverse than prior generations, not because schools are getting better at attracting and retaining teachers of color,” according to the report. “In reality, teaching has grown slowly less attractive to people of color, as evidenced by the larger diversity gaps across generations.”

[Read more at The 74] Read MoreNew Coalition on Transition to Postsecondary

A new coalition of leaders from 18 education organizations, dubbed Level Up, is seeking to alleviate the “stubborn misalignment between K-12 and higher education that too often derails U.S. students from earning a postsecondary degree or credential and becoming economically self-sufficient.” The group wants to measurably increase numbers of high school students, particularly from underrepresented groups, who are prepared for and successfully complete postsecondary education and training programs. It will seek to do so through direct support and research, as well by supporting policies.

“We owe it to all students to not add burdens, frustrations and inefficiencies to their pursuit of something our society very much needs them to do: complete high school, earn a high-quality postsecondary certificate or degree, and enter the work force with the skills necessary to meaningfully contribute,” the coalition said in a new report.

[Read more at Inside Higher Ed] Read MoreWhat are the reading research insights that every educator should know?

If your district isn’t having an “uh oh” moment around reading instruction, it probably should be. Educators across the country are experiencing a collective awakening about literacy instruction, thanks to a recent tsunami of national media attention. Alarm bells are ringing—as they should be—because we’ve gotten some big things wrong: Research has documented what works to get kids to read, yet those evidence-based reading practices appear to be missing from most classrooms.

Systemic failures have left educators overwhelmingly unaware of the research on how kids learn to read. Many teacher-preparation programs lack effective reading training, something educators rightly lament once they get to the classroom. On personal blogs and social media, teachers often write of learning essential reading research years into their careers, with powerful expressions of dismay and betrayal that they weren’t taught sooner. Others express anger.

The lack of knowledge about the science of reading doesn’t just affect teachers. It’s perfectly possible to become a principal or even a district curriculum leader without first learning the key research. In fact, this was true for us.

We each learned critical reading research only after entering district leadership. Jared learned during school improvement work for a nonprofit, while between district leadership positions. When already a district leader, Brian learned from reading specialists when his district received grant-funded literacy support. Robin learned in her fourth year as a district leader, while doing research to prepare for a curriculum adoption.

Understanding the research has been crucial to our ability to lead districts to improved reading outcomes. Yet each of us could easily have missed out on that critical professional learning. If not for those unplanned learning experiences, we’d probably still be ignorant about how kids learn to read.

There’s no finishing school for chief academic officers, nor is there certification on literacy know-how for district and school leaders. Literacy experts have been recommending the same research-based approaches since the 2000 National Reading Panel report, yet there still aren’t systemic mechanisms for ensuring this information reaches the educators who set instructional directions and professional-development agendas. Why should we be surprised to find pervasive misunderstandings?

Here are five essential insights supported by reading research that educators should know—but all too often don’t:

- Grouping students by reading level is poorly supported by research, yet pervasive. For example, 9 out of 10 U.S. 15-year-olds attend schools that use the practice.

- Many teachers overspend instructional time on “skills and strategies” instruction, an emphasis that offers diminishing returns for student learning, according to a Learning First and the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy report this year.

- Students’ background knowledge is essential to reading comprehension. Curricula should help students build content knowledge in history and science, in order to empower reading success.

- Daily, systematic phonics instruction in early grades is recommended by the National Institute for Literacy, based on extensive evidence from the National Reading Panel.

- Proven strategies for getting all kids—including English-language learners, students with IEPs, and struggling readers—working with grade-level texts must be employed to ensure equitable literacy work.

Educator friends, if any of these statements make you scratch your head, you probably have some unfinished learning.

Educators urgently need a national movement for professional learning about reading. We should declare a No Shame Zone for this work—to make it safe for all educators to say, “I have unfinished learning around literacy.”

Superintendents should ask their literacy leaders if research insights are understood and implemented in their classrooms. They must be prepared to invest in the unfinished learning of their team, from teachers to cabinet. Surely some educators will defend misguided approaches; we all tend to believe we are doing the right thing, until research shows us otherwise. On this point, we speak from experience. We encourage superintendents to lean into the national conversation about literacy, in order to ask the right questions.

Some may characterize this national dialogue as reopening the “reading wars,” which pitted phonics against whole language. Frankly, we don’t see it. We don’t frequently hear educators in our districts vigorously defending whole language, as such. More often, they’re simply doing what they believe to work, without knowing better. Instead, we primarily face a battle against misunderstanding and lack of awareness.

For example, some express fears that phonics instruction comes at the expense of students engaging with rich texts, yet every good curriculum we know incorporates strong foundational skills and daily work with high-quality texts. The National Reading Panel got it right: Literacy work is a both/and, not either/or.

The battle against misunderstanding can be won by pairing professional learning with improved curriculum. Quality curriculum that is tailor-built to the research makes good practice tangible and achievable for teachers. Professional development around implementation of such high-quality curriculum is where it all comes together: Teachers are given the what to use, and professional learning explains the why and the how of those materials.

Districts today have many choices among research-aligned, excellent curricula, which was not the case even two years ago. These new curriculum options may be the catalyst we need to improve reading instruction. In each of our districts, we have implemented one of the newly available curricula that earned the highest possible rating by EdReports, a curriculum review nonprofit. Districtwide reading improvement followed.

The gap between good and mediocre curricula is vast. And district teams need a collective understanding of how kids learn to read before selecting new materials. The advances we have personally seen from high-quality curricula have led us to call for a national professional-learning network around curricula to foster cross-district collaboration.

We dream of the potential for children if we embrace this moment of unfinished learning.

[Read more at Education Week] Read MoreOne Reason Rural Students Don’t Go To College: Colleges Don’t Go To Them

The sunrise in rural central Michigan reveals a landscape of neatly divided cornfields crossed by ditches and wooded creeks. But few of the sleepy teenagers on the school bus from Maple Valley Junior-Senior High School likely noticed this scene on their hour drive to Grand Rapids.

They set out from their tiny school district of about 1,000 students, heading to the closest big city for a college recruiting fair. About 151 colleges and universities were waiting.

The students, from Nashville and Vermontville, Mich., were going to the recruiters because few recruiters come to see them.

For urban and suburban students, it’s common to have college recruiters visit their schools — maybe they set up a booth in the lunchroom, or talk with students during an English class. But recruiters rarely go to small, rural schools like Maple Valley, which serves fewer than 450 seventh- through 12th-graders.

“When we think about an urban high school, a college recruiter can hit 1,500 students at a time,” says Andrew Koricich, a professor of education at Appalachian State University. “To do that in a rural area, you may have to go to 10 high schools.”

Rural households also have lower incomes than urban and suburban ones, the Census Bureau reports, meaning that rural students are less profitable for colleges, which often have to offer them financial aid.

“People tend to overlook the rural areas. I think it’s kind of disappointing because some able students could get looked over,” says David Hochstetler, one of the Maple Valley students riding the bus to Grand Rapids. He’s interested in pursuing engineering or computer science in college.

One recent study by researchers at UCLA and the University of Arizona found public high schools in affluent areas receive more college recruiter visits than schools in less affluent areas. Those researchers also found recruiters from private colleges concentrate disproportionately on private schools. Rural areas usually have neither wealthy families nor private schools.

Rural households also have lower incomes than urban and suburban ones, the Census Bureau reports, meaning that rural students are less profitable for colleges, which often have to offer them financial aid.

“People tend to overlook the rural areas. I think it’s kind of disappointing because some able students could get looked over,” says David Hochstetler, one of the Maple Valley students riding the bus to Grand Rapids. He’s interested in pursuing engineering or computer science in college.

One recent study by researchers at UCLA and the University of Arizona found public high schools in affluent areas receive more college recruiter visits than schools in less affluent areas. Those researchers also found recruiters from private colleges concentrate disproportionately on private schools. Rural areas usually have neither wealthy families nor private schools.

Rural parents can also be skeptical of higher education in general, says Julia DeGroot, Maple Valley’s college counselor. DeGroot is the daughter of Grand Rapids white-collar professionals and went to a private high school. For her, she says, “college was never, ‘Are you going?’ It was, ‘Where are you going?’ ” But at Maple Valley, she says, “That’s not the case for these kids.”

“One of the biggest struggles is getting the parents to see that big picture where, ‘It’s OK if my kid goes away to college for four years. It doesn’t mean that they’re never coming back.’ “

Overcoming such perceptions means not only reaching rural students where they live, but getting them to visit campuses, says Andy Borst, director of undergraduate admissions at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign.

“Students come to campus with reluctance, feeling that it may be too big. Once they get there and talk one-on-one to a current student, faculty person or admissions staff, they tend to be less frightened,” Borst says.

But it’s not always easy for rural students to visit a campus. “You have to drive a long distance to actually get somewhere that’s an actual place,” explains Maple Valley senior Sarah Lowndes.

‘A community of nerds like me’

David Hochstetler, the Maple Valley student interested in engineering, met with representatives from Michigan Technological University at the college recruiting fair in Grand Rapids. That meeting helped him decide to attend. The school also sent him an invitation to apply as a “select nominee.” He applied and was accepted early and given a yearly academic scholarship.

He was also able to visit the campus in Houghton, more than eight

hours away by car, because his family vacations on the Upper Peninsula. There, he took a college tour and connected with current students over his passion for engineering.

“Around here [home], there aren’t that many people on the engineering or computer side of things, ” he says. “I thought it would be cool to go into a community of nerds like me.”

This story about rural students was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

[Read more at National Public Radio] Read MoreMemphis school leaders consider proposal to hold back second-graders who can’t read

In an effort to boost literacy among its youngest students, Shelby County Schools has proposed a policy that would require second-graders to repeat the school year if they don’t read on grade level.

The district and state have struggled to get students ready to read by third grade and have heavily invested in literacy instruction. That has led to significant growth in reading scores in Memphis, but literacy rates remain stubbornly low.

Interim superintendent Joris Ray said the policy would ensure what he calls “the third-grade guarantee.”

“We want our students to be positioned to be competitive for the upcoming years because reading is definitely fundamental and it sets our students up for success,” Ray told reporters before a committee meeting of board members began.

The proposed policy would require the district’s 8,700 second-graders to meet eight of 12 points the district already tracks in order to be promoted to third grade. Four of those could come from passing report card grades in English each quarter, three from passing assessments to measure growth in reading skills, three from the state’s program for students struggling with reading, and two from the end-of-year test the district uses from the state.

The district would require students who do not meet the necessary number of benchmarks to attend summer school, where they could catch up in time to be promoted in the fall. The following school year, students would have 45 days to catch up before being required to repeat all of second grade.

About 26 percent of third-graders in Shelby County Schools can read on grade level as measured by the state’s TNReady test. The district wants to get that number up to 60 percent by next year and 90 percent by 2025 because third-grade reading levels are an important indicator of future academic performance.

The district already has a third-grade retention policy that’s not as specific as Burt’s proposed policy.

“The reason we’re addressing second grade in Memphis is when you looking at first grade, fifth month around December, the gap starts to widen,” said Antonio Burt, the district’s chief academic officer. “Nationally, it’s normally first grade, 11th month, which would be June going into the second grade year. Something happens in Memphis where that gap grows faster.”

The policy is modeled after a Florida law that was in place when Burt oversaw school turnaround there. Before going to Florida, Burt led a Memphis school in the district’s heralded Innovation Zone for low-performing schools.

If the policy is approved by the Shelby County Schools board, district officials will track students next year and recommend those who qualify to attend summer school in 2020, but not make it a requirement. The next year, qualifying second-graders would be required to go to summer school or be held back. Parents would be notified by Feb. 1 each year if their child is at risk of repeating second grade. Students who would be fully affected by the policy are this year’s kindergartners.

Burt declined to share his estimate on how many second-graders could be held back based on current data, saying it wouldn’t be valid to judge current students on a policy that’s not in place yet. He did not have an estimate on costs the policy might incur, such as additional second-grade teachers and a communications campaign to explain the initiative to parents and employees.

School board member Stephanie Love said the policy wouldn’t help older students who have already been passed along to the next grade without reading on grade level.

“Kudos to what we’re doing for second grade, but I think we’re still doing a disservice to certain students if we’re not looking at the entire district,” she said during the meeting Tuesday.

Requiring students to repeat a grade in middle school can cause dropout rates to spike, but doesn’t have the same consequence for younger students. Paired with summer school, retaining elementary school students can help in the long run, research shows.

A Michigan law that would hold back third grade students who aren’t reading at grade level goes into effect in the fall. With similarly low literacy rates, parents and district officials are worried a majority of Detroit youth will be held back. So far, the exact meaning of what reading on grade level looks like has not been determined.

Indiana schools use a separate reading test from its regular state assessment to determine if third-graders can read well enough to be promoted. State policymakers have allowed more flexibility for schools to move students to fourth grade as long as they re-teach reading skills if they don’t pass the test.

The proposed policy would require three readings from the school board and would likely come up for an initial vote later this month.

[Read more at Chalkbeat]Diverse: Issues in Higher Education: Report Envisions Path Forward for Educational Equity in Tennessee

Tennessee’s work to increase its residents’ postsecondary attainment levels through initiatives such as the “Drive to 55” campaign, Tennessee Promise and Tennessee Reconnect has positioned the state as a national model, but leaders must not get complacent with the progress made thus far.

That was the sentiment of a new Complete Tennessee report released Tuesday titled “No Time to Wait: The State of Higher Education in Tennessee.” The report reveals that although more than 40 percent of Tennesseans now hold a postsecondary credential, state leaders, educators and community and industry partners can do more to address and close equity gaps in enrollment, retention and graduation outcomes for minority, low-income, rural, undocumented, incarcerated and other underserved groups.

“What was great [about the report] was the understanding that we are now comfortable with saying the word equity. And that is really new, I think, for Tennessee. We’ve always talked about access,” said Dr. Shanna L. Jackson, president of Nashville State Community College and a panelist at the report’s unveiling event. “This work is helping us to look at who’s actually benefiting from those programs and who’s actually completing those programs. It’s causing institutions to think differently.”

Complete Tennessee notes that data, research and researchers’ and practitioners’ expertise should be the basis for the state’s education equity agenda.

“No Time to Wait” offers several key data points for leaders to begin laying the groundwork for strategies to better identify and support subpopulations of students:

- Community college graduation rates have increased from 13 percent to 22 percent since 2013. However, fewer than one out of every four community college students graduate within three years;

- Only one in ten Black students will complete a community college degree, and only a third of Black students graduate within six years of enrollment at Tennessee’s locally-governed four-year institutions;

- Despite Tennessee’s commitment to increasing college affordability, nearly 30 percent of the state’s low-income students enroll at a college or university, which is four percentage points lower than the national average;

- Retention in the University of Tennessee system has increased from 76 percent to 78 percent between 2014 and 2017. Community college retention rates dipped between 2015 and 2016, but increased to over 54 percent in 2017;

- Disparities in postsecondary attainment still persist for Black and Latino students, who hold postsecondary credentials at lower rates than Asian and White Tennesseans.

It will take collaborative efforts from elected officials, higher education stakeholders and institutional leaders to set “ambitious but attainable” annual goals to increase on-time graduation rates and shrink achievement gaps for students across race, income and geographic location, the report emphasized.

Part of the effort to ensure that all Tennesseans have the education and experiences needed to thrive in the workforce will revolve around a need for investment in institutions – particularly in rural and other areas affected by the effects of poverty.

Dr. Jared Bigham, a panelist and executive director of Chattanooga 2.0, an organization committed to increasing postsecondary degree or credential attainment, said this investment is important because geographical location can influence the availability or access to opportunities such as Advanced Placement (AP) or dual-enrollment courses.

Increasing students’ sense of belonging, extending financial support to undocumented students, supporting and implementing programs such as Nashville Getting Results by Advancing Degrees (GRAD) and increasing faculty diversity to reflect the changing demographic of learners are several other opportunities for the state to work towards closing equity gaps, Complete Tennessee leaders said.

Dr. Kenyatta Lovett, executive director of Complete Tennessee, said elevating student and citizen voices can help leaders come up with solutions to the barriers that affect their success. Some of the feedback he has received from students reveals many first-generation students’ experiences with impostor syndrome, some low-income students’ challenge with financial aid verification or potential returning students’ concerns about where to start their process to enter college.

On another front, the early stages of Nashville GRAD would mirror the City University of New York’s Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) model, providing intensive advising support and helping nearly 400 students cover their non-tuition fees such as books, transportation or supplies.

At Nashville State, for instance, Nashville GRAD operates as a system of support for students regardless of their background or how prepared they come to the institution, Jackson said. And even further, the institution has demonstrated a commitment to access and support for incarcerated learners, most recently graduating 23 new alumni from the Turney Industrial Complex.

“We know that education changes lives,” Jackson said. “Finding the resources when [incarcerated individuals] don’t have access to Promise and Reconnect is very challenging, so that is something that we need to wrap our arms around those students as well and give them the supports that they need.”

Industry partners, community organizations and college career counselors can also do their part to engage students about their education and career aspirations starting before students even enter a postsecondary program, the report said.

“Tell students they’re not only getting a degree,” but give them real-time workforce data and experiences to make informed choices about their career plans and potential earnings, said Dr. Douglas Scarboro, senior vice president and regional executive of the Memphis Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Jose Lazo, senior political science major at Tennessee State University, offered closing remarks at Complete Tennessee’s report unveiling, highlighting education as not only the future, but also as the present.

Education, Lazo said, “is a transformative power like none other that can within one generation, transform society itself.”

[Read more at Complete Tennessee] Read More