As Free College Tuition Becomes a Popular Rallying Cry, ‘Tennessee Promise’ Hailed as Game Changer — but Equity Concerns Remain

Lake County, population 7,500, the bubble-shaped piece of land in Tennessee’s northwestern corner, is wrapped by the Missouri River that separates it from two bordering states. Tiptonville, its biggest town and county seat, has a state prison and a small tourist attraction noting the birthplace of rockabilly legend Carl Lee Perkins, best known for writing and releasing the original “Blue Suede Shoes.”

Lake County is also the state’s poorest: Nearly 43 percent of adults and 49 percent of children live in poverty. Further, it’s the least-educated county in the state; less than 12 percent of adults have at least an associate’s degree.

That’s the challenge facing Michelle Johnson and Tonya McKellar, the counselors at Lake County High School, who are trying to push the 45 members of the class of 2019 to continue their education. An essential part of their arsenal has been Tennessee Promise, a four-year-old program that covers tuition and fees at community college or technical school for any high school graduate in the state.

“It’s just the whole culture that we have to change, and that’s not just the students. It’s the county. It’s the parents. It’s everybody,” McKellar told The 74 during a visit in mid-December.

The program is part of former governor Bill Haslam’s “Drive to 55” initiative to get 55 percent of Tennessee residents to earn a college degree or certificate by 2025. The broader program, which also now includes free community college for adults without degrees, was initially billed as an economic development and workforce initiative to, as Haslam put it, “ensure Tennesseans get Tennessee jobs.”

But Tennessee Promise is also having an impact earlier in the educational pipeline, changing the college-going culture in the Volunteer State’s high schools, both rural and urban, advocates and counselors told The 74.

“I think Promise has been a game changer for the culture in high school. It’s no longer about if, it’s about where you’re going to college,” said Krissy DeAlejandro, executive director of TNAchieves, a nonprofit that runs the program’s required mentoring and college orientation programs in much of the state.

“We often hear from students who say, ‘I’m the first one in my family to go to college, and now my siblings want to go to college,’” she said.

The program is increasingly being looked at as a national model, as other states emulate and expand on Tennessee’s example and progressives have made free college tuition a political rallying cry.

Even within the state, the idea of “free college” recently became even more expansive, when the University of Tennessee in March announced free tuition at three of its campuses for students who meet certain academic requirements and whose families make less than $50,000 a year.

Though widely praised — including by former president Barack Obama, who sought to replicate it at the federal level — Tennessee Promise does have its critics, primarily those who say its benefits primarily flow to students from higher-income families rather than those most in need. Undocumented students aren’t eligible, and research has shown lingering equity gaps despite the program’s near-universal accessibility.

The class of 2019 is just the fifth eligible for the program, so research on its impacts on students’ K-12 experience isn’t yet available. A study of a similar program for students in Kalamazoo Public Schools in Michigan showed that it resulted in more credits earned, higher grades and fewer days in detention or suspended in high school, particularly for African-American students.

Across Tennessee, 63.4 percent of the class of 2017 enrolled in higher ed the fall immediately after graduating from high school, up 5 percentage points from the class of 2014, before the program began.

“More kids are thinking they can have the opportunity to go to college with the Tennessee Promise, where they wouldn’t have before,” said Johnson, the counselor at Lake County.

The program, the first in the country to offer nearly universal access to all graduates, has been a lifeline for students who didn’t take their academics seriously early in high school, said Yolanda Grant, a counselor at Ridgeway High School in Memphis for the past 12 years.

“We don’t want them to think that because I didn’t do my very best in ninth, 10th and 11th grade, I don’t have any options. So with the Tennessee Promise, they still have an option,” she said.

State higher ed officials don’t keep track of recipients’ class rankings or high school GPAs, but they have seen that students in the program tend to have ACT scores “on the lower end,” said Emily House, chief policy and strategy officer at the Tennessee Higher Education Commission.

Research that House and her colleagues at the state agency presented to the state legislature in March 2019 also showed that the rate of remediation in Tennessee colleges is on the rise, which she attributed to the expanded attendance pool, including those who got lower ACT scores.

Although many of those low-scoring students would’ve enrolled in college before Tennessee Promise, more are doing so now that community college is increasingly accepted as part of the higher ed landscape, she told The 74.

“At the student level, it’s shifting this level of conversation around what it means to go to college,” she said.

‘They didn’t know what they were missing’

Johnson and McKellar, the Lake County counselors, are zealous about completing applications for Tennessee Promise.

One hundred percent of the class completed the basic application forms before The 74’s visit in mid-December. The eight stragglers who hadn’t finished the federal financial aid application required at all colleges, and for Tennessee Promise, did so by the Feb. 1 deadline.

That effort to complete the Tennessee Promise application, with its early deadlines, means students benefit even if they don’t ultimately use the program, McKellar said.

“It gives you a mindset of ‘We’re all working together to get to a certain point,’ and it all gets done early. That’s a big push,” and it has helped students earn other scholarships, she said.

The push has made students more receptive to college in general, Johnson said. “I think before, they didn’t know what they were missing.”

Johnson and McKellar expect 60 to 70 percent of this year’s class to go on to some form of higher education. That’s up from the 43.1 percent of the class of 2017 who went immediately to higher ed, according to figures from the state Department of Education.

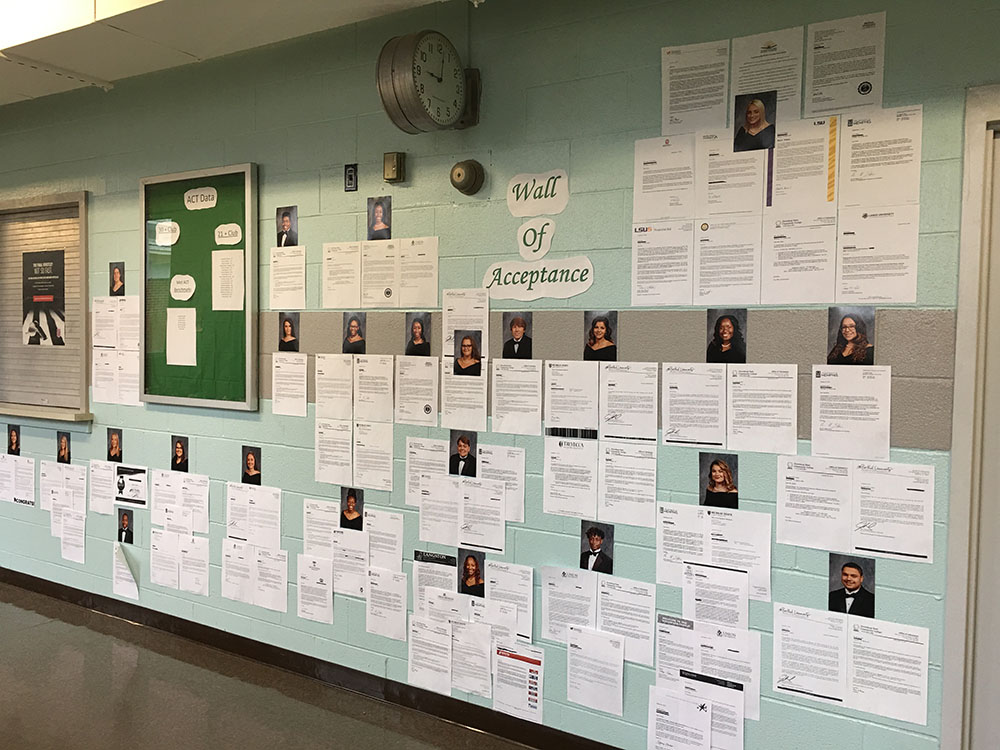

A wall at Lake County High School showcases where students have been accepted to college. (Michelle Johnson/Lake County Schools)

About half of the class of 2017 who went to higher ed attended community college, and the counselors say that’s likely to continue, with many headed to Dyersburg State Community College, a 30-minute drive from downtown Tiptonville.

Many students will use their two free years as a springboard to a four-year degree.

Johnson’s own daughter, who initially intended to spend all four years studying pre-K-3 education at a four-year school, decided to take advantage of the two free years at Dyersburg State before transferring.

But the opportunities come with a downside: Sending students out of Lake County for higher ed often means they won’t come back.

“There’s not a lot in Lake County, not a lot of opportunities in Lake County for folks with degrees” outside of education, Johnson said. “We have some very successful folks, but the majority of them stay out of Lake County.”

Though Johnson and McKellar encourage all students to maintain their Tennessee Promise eligibility, just in case of changed plans or family circumstances, only about 20 percent will actually use the grants. Many students, who come from very low-income families, will instead be covered by federal Pell Grants, Johnson said.

Tennessee Promise is what’s known as a “last-dollar” scholarship, meaning it covers tuition and fees only when other financial aid has run out. Pell provides up to $6,095 per year depending on family need. For many of the lowest-income students, Pell covers all the tuition and fees that would otherwise come from Tennessee Promise grants, so they don’t see any financial benefit from the program.

That lack of help to the neediest students is among the primary criticisms of the program. Advocates have argued that limited state dollars should be better targeted to the lowest-income students — for example, by paying for four-year degrees or helping with housing and living expenses that exceed Pell awards.

State officials say the lowest-income students do benefit.

“I understand the logic, because yes, these [Pell Grant-eligible] students don’t get [state] dollars. But I think even the lowest-income students get so much from this program,” including help filing their financial aid applications, mentoring and a general stronger college-going culture, House, the state higher ed official, said.

Memphis’s Ridgeway High School class of 2018 celebrates its graduation. The Tennessee Promise free community college has proved particularly valuable as a higher ed path for students who didn’t take academics as seriously early in their high school careers, staff said. (Shelby County Schools)

In an ideal world, all free college programs would be “first-dollar” and cover all college costs without considering other aid a student may receive, “but that is very rarely going to be politically feasible, financially feasible,” House added.

Both Johnson, at Lake County, and Grant, at Ridgeway, said they’ve helped low-income students who have encountered that problem. In the end, they say, it doesn’t particularly matter to the students where the money is coming from, so long as they get it.

Statewide research, on the other hand, showed that while the rate of community college completion has risen dramatically in the wake of Tennessee Promise, relatively few low-income students enroll in postsecondary education, and wide racial gaps in degree completion remain.

Physical access to Tennessee Promise-eligible schools has been an issue, too.

The northwestern corner of the state is particularly disadvantaged. Only 29 percent of Lake County residents have access to a community college within 25 miles, according to state figures.

Dyersburg State Community College, the most popular choice for Lake County students, is the closest, and students can also use Tennessee Promise to attend two nearby colleges of applied technology.

But beyond those schools, Lake County’s unique geography means that community colleges in bordering Missouri and Arkansas are closer than many in-state, Tennessee Promise-eligible schools.

State higher ed officials are keeping track of those higher ed deserts, House said, and are working with some K-12 districts to keep the buildings open for adult education offerings.

‘A backup plan’

It’s not just in rural Tennessee that the program is making a difference.

In Memphis, students at Ridgeway often say they had a plan to go to college but weren’t really putting anything into action before the additional push from Tennessee Promise, Vice Principal Taurin Hardy told The 74.

“Now they’re doing it. Now they know they have that financial stability, that financial backing. That’s a huge barrier for a lot of kids, especially kids of color,” he said.

For students who don’t need that extra reassurance, the program can also be something of a fallback.

As of mid-December, Alexis Jefferson, a Ridgeway senior, had been accepted into two four-year colleges where she hopes to study business and marketing, on her way to a job advertising toys. But if those don’t work out, she can use Tennessee Promise to study at Southwest Tennessee Community College.

“It’s sort of like a backup plan,” she said.

Such attitudes are a distinct shift from the early days of the program, when Tennessee Promise was a difficult sell, Grant, the Ridgeway counselor, said.

Students were put off by the stigma of community college as “13th grade” and not real college.

“Now it’s easy. They know that ‘I have an option. Although my parents may not be able to afford college, I can still go.’ For a lot of them, this is their No. 1 choice … They know they can still get a quality education,” she said.

[Read more at The 74] Read MoreTNReady tests expected to be included on student report cards after successful test year

Tennessee districts should have online TNReady scores available by the end of the school year, ensuring they can be used in student final grades.

Tennessee Department of Education spokesman Jay Klein said districts will get online raw scores for high schools to districts by May 20. Paper tests in grades 3-8 were required to be submitted on Monday to get results by that time.

Results will be delivered after the first TNReady online testing season that didn’t involve statewide problems.

About 2 million tests were completed statewide and almost 1.4 million were submitted online, according to a news release from Tennessee Education Commissioner Penny Schwinn. The state’s testing window closed on Friday.

The education department said in the announcement that there were minor issues in schools related to user error or local infrastructure limitations, but the state’s computer-based testing process was completed without a major incident.

This year’s testing window marks the first where Tennessee hasn’t had issues with its vendor and online testing.

Last year, the state saw widespread problems after Questar Assessment made unauthorized changes to the test platform.

Previous years also proved problematic. In 2017 Questar Assessment and the state didn’t deliver raw scores to districts on time.

And in 2016, then-test vendor Measurement, Inc. couldn’t handle the administration of online testing for the state. It caused the state to cancel testing in elementary and middle schools.

[Read more atTennessean] Read MoreBuilding On Tennessee’s Foundations For Student Success

Tennessee’s foundational policies in academic standards, annual assessment, and educator evaluation provide the fundamental building blocks of a high-quality education system. As Tennessee considers future opportunities to accelerate student learning, our collective commitment to these essential policies enable the practices and innovations that will propel our students to the success we all know they can achieve.

One of the priorities in the State Collaborative on Reforming Education (SCORE)’s 2018-19 State Of Education In Tennessee report focuses on Tennessee’s foundations for student success and the need to maintain the student-focused policies and practices that have driven unprecedented progress in student achievement, with greater emphasis on ensuring equity for all Tennesseans.

What were innovations a decade ago have become the bedrock for Tennessee’s current and future success. As Tennessee rebuilds confidence in the annual assessment system with students, educators, parents, and other education stakeholders, it is important to recognize how these policies have contributed to student success and the opportunities they present for Tennessee to build a world-class education system that gets better at getting better.

There is evidence that Tennessee students have learned more and educators have grown more during the time period that these policies were implemented when compared to other states:

- A Stanford University scholar’s in-depth analysis of student achievement trends across the country showed that from 2009-2015, Tennessee’s student achievement gains stood out both when comparing to other states and for the relative consistency of gains across Tennessee’s districts.

- Building on previous research by Brown University scholars, research from the Tennessee Education Research Alliance found that Tennessee teachers grew more in recent years, with Tennessee teachers improving more than their peers in other states.

- On the 2018 Tennessee Educator Survey, 69 percent of teachers said they believed Tennessee’s multiple measure teacher evaluation process led to improvements in their student learning. This is compared to 28 percent in 2012.

This unprecedented progress in both student and teacher growth is unique to Tennessee and suggests that the state has built the foundations for an education system that prioritizes and facilitates continuous improvement. It is a signal of Tennessee’s belief in the promise of what students and educators can achieve.

At the heart of these policies is how they help all students – regardless of where a student lives or their life circumstances – learn the skills and knowledge they need to be ready for college, career, and life. Tennessee’s academic standards provide a framework for rich learning experiences aligned to a thoughtful progression of concepts, skills, and content across grades. Combined with higher quality standards in other subjects, the standards provide a common set of expectations across the state while enabling local districts and educators to design the content-rich learning experiences students need.

With a clear set of learning goals, measuring student progress through an aligned, high-quality annual assessment allows students, parents, and educators to reflect on what was – and more importantly, was not – learned. The state’s current assessment, TNReady, has helped address Tennessee’s “honesty gap” and gives a more accurate snapshot of student learning.

In the past, the misalignment between the state’s test and national assessments of student learning helped hide inequities in learning outcomes for students of color, economically disadvantaged students, and students with disabilities. With implementation challenges in recent years, Tennessee deserves nothing less than a flawless TNReady administration in 2019 and beyond. Over time, each successful administration will help Tennesseans better understand and evaluate how well our public education system serves every student.

Research has consistently found that teachers and school leaders are the first and second most important in-school factors for student learning. Tennessee’s multiple measure evaluation system honors the essential role educators play in our education system by providing regular feedback on their practice from other educators as well as data on student learning.

When paired with high-quality professional learning, Tennessee’s educators get the support they need to grow as professionals. Local and state efforts to ensure equitable access to effective teaching, improve teacher preparation, and better develop teachers depend on a reliable understanding of teacher effectiveness. While more work remains to ensure observation feedback better matches current teacher needs, Tennessee educators overwhelmingly accept the premise that these evaluations help improve their craft. In future years, we will know even more about the work to improve teacher effectiveness because of Tennessee Education Research Alliance’s research.

The statewide alignment enables state policymakers to provide the right types of support to districts and educators without standing in the way of local innovations that improve student learning. From the 2020 English language arts instructional materials adoption to conversations about how to redesign the high school experience, districts and educators are empowered to design the opportunities that make the most sense for their communities while having a strong set of goals and processes to ensure that both students and teachers grow.

By adopting rigorous college and career ready standards for student learning, a high-quality assessment aligned to those standards, and a multiple-measure accountability system to provide feedback to educators, Tennessee created a policy environment that enables and encourages educators to deliver high-quality learning experiences year after year.

[Read More at SCORE] Read MoreSchool vouchers are coming to Nashville and Memphis: What it means for students and parents

A school voucher plan is coming to Tennessee’s two largest counties.

The education savings account program was a centerpiece of Gov. Bill Lee’s legislative agenda this year, and the General Assembly gave final approval to the plan on Wednesday.

The House and Senate had passed vastly different versions, and a conference committee gathered Wednesday morning, and after less than 30 minutes, approved a compromise that ironed out the differences.

On Twitter, Lee said the bill “provides more choices for more students and families.”

“This is an important day and I look forward to signing this bill into law,” Lee said.

So what’s in the final version of bill and how would it work? Here are some highlights:

What are education savings accounts?

Education savings accounts provide public money for parents who unenroll a student from their school district and allow them to use the funds on private school or other education-related expenses.ADVERTISING

Parents enrolling in the program would get debit-style cards to pay for tuition or the other approved expenses.

How much money would a student get?

On average, the state spends about $7,300 per student on education. That’s the amount, on average, a family would receive each year into their education savings account.

How many kids will be able to use the program?

The program, which would start in the 2021-22 school year, would apply to up to 15,000 by the program’s fifth year. Here’s how it would break down. BY THE SALVATION ARMYGetting rid of furniture? Don’t haul it yourself.See more →

- 5,000 students in the first year.

- 7,500 students in the second year.

- 10,000 students in the third year.

- 12,500 students in the fourth year.

- 15,000 students in the fifth year.

Which districts are targeted for the education savings account program?

Originally, students in five counties would have been eligible to participate in the program: Shelby, Davidson, Knox, Hamilton and Madison counties.

But later versions applied to just four and the final version only applies to Shelby and Davidson counties. In addition, students enrolled in schools overseen by the state-run Acheivement School District would also be eligible.

The ASD takes over the worst-performing schools in the state, and often turns operations of them over to charter schools, and largely works in Shelby and Davidson counties.

Are home-school students allowed to participate?

No. That was one of the differences lawmakers had to compromise on.

The Senate version of the bill allowed parents to unenroll a student from a public school and home-school them instead and use the education savings account for related expenses. The House version did not include that provision.

Are there testing requirements?

Yes. The bill only requires that students take the standardized math and English exams. It removed a House mandate that students in the program take the TNReady social studies and science tests.

Are there income requirements?

Yes, the program applies to low-income families. A student’s household income must meet the same requirements as the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program.

To verify eligibility, a household would have to provide a federal income tax return or proof that the parent of an eligible student is eligible to enroll in the temporary assistance program.

Eligibility, particularly whether a student who entered the country illegally as a child could participate, has been a sticking point for some lawmakers.

Sen. Todd Gardenhire, R-Chattanooga, blasted the legislation because of a provision that would prohibit families with undocumented students from receiving money. Gardenhire previously voted for the bill but switched to a no on Wednesday.

A 1982 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that says students who entered into the country illegally can’t be denied a public education. School districts do not ask the immigration status of students.

What responsibility do the districts have to your student if you participate?

In short, a district would have no responsibility to the parent if they unenroll children from their school.

Both bills say that parents must release the district from “all obligations to educate the participating student while participating in the program.”

What is the cost to the state?

That’s a good question. It all depends on how you account for the money and how many students participate in the program.

And lawmakers don’t agree, either, on the full cost. In fact, questions over a fiscal analysis of the bill forced Senators to delay their vote Wednesday. A new, updated analysis was later released.

At it’s core, here’s how the finances would work.

The plan would tie state funding for education to the student. In this case, the roughly $7,300 per student would go into the ESA.

The state would shift money away from Tennessee’s Basic Education Program to fund the education savings accounts. That’s all existing money, through a combination of state and local sources.

Then an equal amount of money would go into a new school improvement fund for three years starting in fiscal 2021-22 when students can begin enrolling.

That new fund would provide grants to Metro Nashville Public Schools and Shelby County Schools to make up for the money that the districts lose when the students participating in the ESA program leave a public school.

That’s new money — $165 million over three years based on full participation in the program. There would also be administrative costs.

But it’s not as simple as that.

The state is not projecting full participation in the program, and wants to set aside $25 million a year, plus money for administrative expenses, to cover the program’s costs.

[Read More at Tennessean] Read More

The Next Step: Students Graduate, But Are Not Ready

By Tara Scarlett

A shorter version of this piece originally ran in the Tennessean. https://www.tennessean.com/story/opinion/2019/04/26/nashville-students-graduating-high-school-unprepared/3554911002/

Next month, Metro Nashville Public Schools (MNPS) will celebrate another graduating class with pomp and circumstance. They will bestow upon our high school seniors a diploma, a mutually understood signal that these students are ready to forge ahead to college or the workforce.

In reality, most of them are not.

The 2017-2018 Tennessee Department of Education report card shows that 80% of our students graduated high school on time. However, this same report also shows that 3 out of 4 MNPS students did not score a 21 or higher on the ACT, which is the state’s marker for– and a widely accepted indicator of– college and career readiness.

The situation becomes even more dire when we realize that the state assessment indicates 89% of our high school students are not proficient in grade level math; and 81% are not proficient in grade level English Language Arts.

These averages only scratch the surface. When we dive deeper into the data on specific MNPS high schools, as the Scarlett Family Foundation has done, we see rates of chronic absenteeism (students missing more than 10 days) as high as 30, 40, even 47 percent. We see that almost every student zoned for Whites Creek High will attend a priority school (a school measuring in the bottom 5 percent statewide for student growth) for every year of their education. And we find that in eight out of the twelve traditional MNPS high schools, the average ACT score is below 18.

These numbers demand a city-wide conversation.

Whether that conversation takes place between a student and a teacher, teacher and a principal, a teacher and a parent, or a parent and their child, the data we have available to us can start a transformative discussion on what is needed to support every child’s education.

At the Scarlett Family Foundation, the heart of our work is a four-year college scholarship awarded annually to students who graduate from a high school in Middle Tennessee and will major in Business or a STEM field. The practice of reading these applications year after year gives us a deeper understanding of who our Middle Tennessee students are.

This year, we were tasked with selecting finalists from a pool of almost 2,000 applicants. This required hours of careful— and sometimes painful— consideration.

Many of these students blow us away with their smarts, drive, passion, and dedication to the community. But far too often, we see applicants at the top of their class, earning GPAs of 4.0 or even higher, with ACT scores that are several points below a college or career-ready score of 21. How is this possible?

In the essay section, applicants’ responses are often riddled with spelling and grammatical errors, and lack basic coherence, structure, and message. It is unlikely that these students will be able to write at the level expected in an institution of higher education or in a workplace.

Yet, every May, MNPS says to our students: you are ready for the world. Take it on! Make things happen! And year after year, MNPS hand over a new round of diplomas, even as our community is confronted with data that tells us only 25% of these students are actually ready for the next step. We tell our students they are prepared for post-grad success while simultaneously ignoring the warning signs we can see clearly in front of us.

Who does this willful ignorance serve? The reality is that the other 75% of MNPS students will likely struggle to find and keep a job that pays a living wage, or will spend their first year at a college or university in remedial courses.

Imagine the disappointment, discouragement, and heartbreak these students will have to stomach when they realize that 13 or 14 years in our public school system did not actually prepare them for a prosperous adulthood.

This is an injustice to our children. So, what can you do?

We all have different levels of capacity in this fight. But if you feel outraged by the state of our schools, there are many ways to plug in and make a difference.

- Share the data and the stories. Nashville needs more people to get involved in helping to turn around our schools. This is an undertaking that serves all of our kids – no matter if you live on the Westside, Northside, Eastside or Southside. Every single child in Nashville deserves access to a high-quality school.

- Raise your voice in front of your elected officials. Demand a triage plan to help students who are in school today. We are witnessing a public education system in crisis, beginning with early childhood education and continuing through to adulthood. Be vocal.

- Volunteer your time to address root issues. To be most successful in their academic futures, children need to be reading at grade level by third grade. Become a mentor to a high school student, or read to 20 minutes a day to a child who needs it. Today, only 25% of our third graders have mastered or are on track to mastery in English Language Arts, and math proficiency is even worse.

- Support great principal and teacher talent development by advocating for increased professional development and practice sharing in the teaching community. See the Tennessee State Board of Education’s ranking of top programs for aspiring educators.

Whether you are ready to be a boots-on-the-ground problem solver, or prefer to play the role of an outside advocate, Nashville needs you.

We cannot keep turning a blind eye. Instead, let’s band together and push for transformative change that will allow all high school graduates to succeed after graduation, whatever pathway they choose. The children of Nashville deserve this— and our city is worth it.

Tara Scarlett is President & CEO of the Scarlett Family Foundation.

Tags: MNPS Cluster Profiles

Graduation Guides Promise High Schoolers A Clearer Path To Success

Aniya Cox is sure she wants to be a dermatologist. What she’s been less sure about is what she needs to do to get there — she’s just 16, a sophomore at Eastern Senior High School in Washington, D.C.

She can remember, at various points of the past two years, desperately trying to navigate all that’s required to graduate high school and get into college.

“I was all over the place, I was frustrated,” Cox said. “I didn’t know what I needed to do.”

Cox said even the process of asking her teachers for advice — and finding time to meet with them — was confusing.

Today, D.C.’s public schools are rolling out an intervention they hope will address concerns like Cox’s. Twice a year through the fall semester of senior year, high schoolers in D.C. will now receive a document that tracks their progress towards graduation requirements and gives them information about college and career options. The district is calling it a “Guide to Graduation, College, and Career,” and it’s a PDF personalized for each student. The guides, which will be mailed and available online, are part of the district’s efforts to boost college and career readiness among its students — and part of a larger movement across the country to make education data more available and accessible.

The implementation comes just one year after D.C.’s Office of the State Superintendent of Education found 34 percent of D.C.’s high school graduates hadn’t actually met the requirements for receiving a diploma. D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser requested the report days after NPR and WAMU published a story that found students had missed months of class at D.C.’s Ballou High School but were still permitted to graduate.

Last year, D.C. reported that its graduation rate for black and Latino students dropped. The Office of the State Superintendent said it used additional levels of verification to calculate graduation results as part of its ongoing monitoring of the school system’s graduation policies.

“It’s definitely an enhancement to our transparency around graduation,” said DCPS Chancellor Lewis Ferebee of the guides. “It’s a way that we can monitor, along with families, where students are on their journey to graduation.”

Ferebee also said the guides are part of a larger strategy to boost enrollment at high schools that have been losing students. They will help promote more college and career-related programming, which parents have been asking for. He said the guides can be used “to connect those options with student interests and goals.”

Ferebee and Bowser announced the rollout of the guides, along with two new early college programs at DCPS high schools, at a press conference Thursday.

The DCPS guide is a 7-page document. It includes an unofficial transcript along with information about progress towards graduation requirements, likelihood of admission to area colleges and universities and a personalized guide for career opportunities.

If a student is not on pace to graduate, those sections of the report appear in red. If a student’s academic record says they aren’t on track with History credits, for example, the guide will say so. The packet also contains a map of college choices, categorized as “likely,” “match” or “reach” schools based on the student’s SAT or PSAT score and GPA. And it ends with a section on careers that contains personalized sample jobs — and projected salaries — for each student (Each DCPS high school student fills out a survey indicating future career interests at the start of each school year).

A few other school districts in the country — including Long Beach Unified, Orange County Public Schools and Chicago Public Schools — have already begun using similar guides.

In Long Beach, the public school district is in its second year of implementing them. Robert Tagorda, Director of Equity, Access, and College & Career Readiness for the district, said the guides are popular — and Long Beach is now planning to roll out a high school readiness guide for its middle schoolers.

Tagorda said the guides can’t be viewed in isolation. Long Beach partners with the University of Southern California on college advising and almost half of its 11th and 12th graders enroll in at least one AP course. Well before the guides were implemented, the school district was seeing increases in test scores, graduation rates, and college-attendance rates.

But Tagorda also said the guides themselves have value. Distributing them, for him, is a matter of equity, and has helped to ensure the quality of counseling and support for students is standardized across the district. In addition, he says, the guides are helping Long Beach make a complicated process digestible — and accessible to families of all backgrounds.

“Students are inundated with data,” Tagorda said, but, “What students and families want to know is, ‘What do I need to really understand that will make a difference for my student’s admission to college?'”

Back in D.C., the guides are a kind of insurance policy, explains Daniel West, who runs the college and career readiness program at D.C.’s Eastern Senior High School. Even if a student is not meeting with their counselor as they are supposed to, the school system is still equipping them with easily digestible information and advice.

“Even if that student doesn’t continue to engage with adults in the building who want to help provide them with resources, they now have a document they can work with by themselves,” West said.

D.C. officials say the guides will be made available in the three languages spoken most commonly among DCPS families — English, Spanish and Amharic. Translation help for additional languages will be available by request. Mailing a paper copy is also really valuable, explains Aniya Cox, the sophomore at Eastern High, since not all her classmates have consistent access to the Internet.

The most immediate concern, for Cox, is getting community service hours: on her guide, that section is highlighted in red because she hasn’t completed any of the 100 hours D.C. requires of its students. Her summer is open still, so she’s hoping to get her service hours in then.

“I really need to get that done,” she said with a chuckle, her eyes widening. “I really need to get that done.”

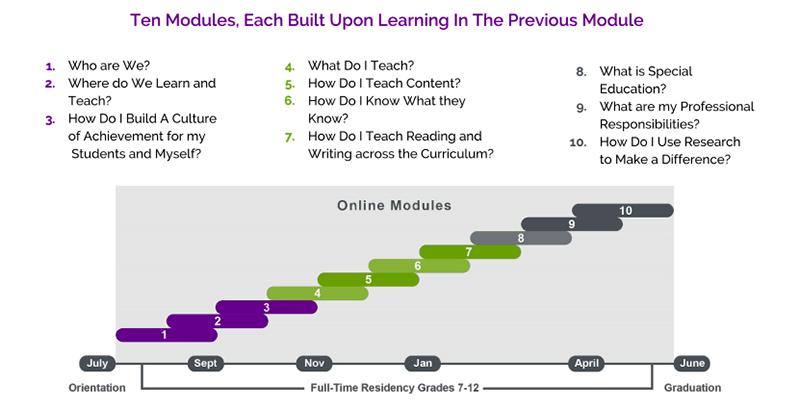

[Read more at National Public Radio] Read More3 Ways NYU Is Training New Teachers to Use Special Ed and ELL Strategies to Better Serve All Kids

Skills acquired by NYU teaching residents. (New York University)

New York University is expanding its novel teacher training program, which places diverse teachers into high-needs schools for an intensive, yearlong master’s program organized around the belief that all teachers benefit by learning to work with students with disabilities and those learning English.

The Steinhardt’s Teacher Residency program combines online academic preparation with full-time classroom placements in districts and public charter schools in four states. Now completing its third year, it has grown from serving 10 interns to 75. The program’s goal is to have at least 40 percent of each class of teacher residents be candidates of color, according to an NYU spokesperson. More than half of members of the first three groups have been people of color.

A recently announced $481,000 grant from the Walton Family Foundation will support the program going forward. Here are three of its big strategies.

1. All teachers will learn special education and English-language-learner strategies.

The NYU program has taken a signature approach to training new teachers to work in classrooms where students have diverse and intense needs. All teacher candidates in the program learn not just to teach in a content area such as math or English, but also to adjust their instruction to reach all students.

“All of our interns are going to be in inclusion settings,” said Diana Turk, the program’s director of teacher education, referring to classrooms where students receive special education services alongside general ed students. “They’re going to be more effective teachers for all students, not just for their students with [disabilities].”

As U.S. classrooms become more diverse, teachers are increasingly required to tailor instruction to students with vastly differing needs. The methods employed by special education teachers in particular can help fill this gap.

It’s a unique way of addressing a long-standing problem. Traditionally, colleges of education have treated teaching students with disabilities and students learning English as specialized skills needed only by those who will work intensively with those groups, often in a separate classroom. General education teachers-in-training may get brief exposure to strategies for meeting those students’ needs, and in some places an extra degree or credential is required.

Among other factors, this has compounded shortages of special ed and English-language-learner teachers, even as demand for them has risen.

From 2005 to 2015, the number of special education teachers in the United States fell by 17 percent, while the number of students in need of their services decreased just 1 percent, according to Education Week.

In 2016, 32 states reported shortages of teachers of English language learners, even as the number of students needing their services climbed by 1 million between 2000 and 2015 to 4.8 million.

2. Including “emergent bilinguals” and students with disabilities will be the rule, not the exception.

At the same time, schools increasingly recognize the value of serving both groups of students in mainstream classrooms, where their increased numbers now make them as common as any other student demographic group. Arrangements for meeting their needs in general education classrooms, however, range from “push-in” services, where specialists pop in to offer support, to placing two teachers, one with the requisite skills, in a single classroom.

NYU’s graduates will have all three sets of skills, said Ayanna Taylor, a professor in the program.

“We wanted to make it such a central part of our curriculum that that there was no segmenting off,” she said.

3. New teachers will demonstrate their abilities before getting a classroom of their own.

After teaching for a year in New York, California, Florida and Pennsylvania in settings as varied as San Francisco Unified School District and a number of small charter schools, some with a focus on including students with disabilities, NYU’s residents will earn a master’s degree. If trained observers rate them as effective or nearly so, they will be recommended for a New York state teaching credential.

[Read More at The 74]Metro Nashville Public Schools Interim Director Adrienne Battle shares vision for district

The Metro Nashville Public Schools board welcomed the district’s new interim director at its April 23 meeting.

Adrienne Battle, who officially began the temporary position April 15, replaced former Director Shawn Joseph following the board’s April 9 vote to buy out his contract.

“This is a great opportunity, and it is even a greater responsibility,” Battle said.

During her first meeting as interim director, Battle outlined her three main goals for the district: prioritizing students, eliminating “distractions” and setting high expectations for students, teachers, staff and administrators.

“Students are at the core of what we do,” she said. “Everything we do must benefit them and their pursuit of a diploma … this begins as early as pre-K and kindergarten.”

Battle said she also believes in setting high expectations for the district’s 86,00 students and more than 11,000 administrators, staff and teachers. High expectations must be met with support, Battle said, adding she plans to prioritize employee compensation during her tenure.

“As an administrator, part of my job is to make sure our teachers and the other MNPS employees have everything they need to provide a high level of support to students,” she said. “Employees take care of our students, and I want to take care of them, because when you combine high expectations with high support, you get great student outcomes.”

With the last day of school for MNPS set for May 23, Battle said she encourages the district to “eliminate the distractions” by focusing on tasks such as end-of-year testing.

“The third thing we must do is eliminate the distractions, especially as we are currently in testing season … it’s what the system requires and what our students deserve,” Battle said. “We need better listening. We need more informed decision making. We need to keep more of our focus on the students and less of it on the things that distract us from our goals.”

Before accepting the position, Battle worked as a community superintendent overseeing all schools located in the district’s southeast quadrant. The board has not determined the details of Battle’s contract or the duration of the position as of April 23.

[Read more at Community Impact Newspaper] Read More

A City on the Move. Students Left Behind.

Our city is growing at a breakneck pace. Consider the constant headlines on new industry setting up shop in Nashville: Amazon, E&Y, Philips, and Alliance Bernstein are committed. Oracle is in talks. And we can’t ignore the boost in tourism brought by the NFL Draft, the Predators reaching for the Stanley Cup, and a continual stream of talented musicians showcasing their songs. Music City is booming. As we stare this new economic landscape in the face, we must acknowledge that our growth is outpacing our ability to provide homegrown talent to the local workforce. It has never been more important to focus on Nashville’s K-12 public education system.

From a district-level perspective, we can see immediately that something is wrong. Three out of four of third graders aren’t reading on grade level. Almost 20% of students are chronically absent from school (missing 10% or 18 school days). And three out of four MNPS high school students did not score a 21 or higher on the ACT, a widely accepted indicator of college and career readiness. Our public education system, the foundation of our community, is crumbling. The benefits of the economic boom in Nashville are not extending to all residents — particularly our MNPS students.

In order to tell the whole story, we realized we needed to zoom in, to see in greater detail how specific schools and neighborhoods are performing— to see how Hillsboro compares to Antioch, and how Whites Creek stacks up to McGavock.

The critical question is: are students ready for life when they graduate from high school?

One way to tell is to look at each “cluster” of schools.

MNPS is divided into 12 clusters, or zones, with all elementary and middle schools feeding into one high school per zone. Students are zoned to their cluster of schools according to their address, and will follow a zoned pathway from elementary to middle to high school. Families in Nashville do have choice, though, meaning they can opt to apply to a magnet school, non-zoned school or public charter school even if the school is not in their assigned zone.

There is so much data to explore; and that is why this is only the first in a series of blogs that will unpack the information found in our MNPS Cluster Profiles. In future pieces, we will be looking closely at the readiness of high school graduates, district enrollment trends, and teacher retention, among other topics.

Lowest-Performing Schools concentrated in three neighborhoods

The number of priority schools (schools ranked in the bottom 5% statewide) in Nashville has increased in the last three years— to 21 total. As we look at the location of these schools, we see that they are largely concentrated in three neighborhood zones: Whites Creek, Maplewood and Hunters Lane.

Students in these three zones are likely to attend not just one, but two or even three priority schools during their K-12 years. If dramatic improvement is not made, a majority of students in the Whites Creek cluster will attend a school in the bottom five% statewide for every year of their education.

Great schools, but not in every neighborhood

Similarly, our city’s highest achieving schools are concentrated in just a few neighborhoods. Hillsboro, Hillwood and Overton zones have the highest performing high, middle and elementary schools. Many of the traditional schools that meet or exceed the state averages for English and Math achievement are located within these three neighborhoods.

Another significant observation: of our 22 Reward schools (schools recognized by the state for making gains in student growth and achievement), only nine of them are actually within the traditional cluster pathways— one, LEAD Cameron Middle, is a charter school. Six of them are non-zoned MNPS schools and have additional admission requirements (such as academic magnets). Another seven are non-zoned charter schools. These public charter schools practice open enrollment, allowing for any Nashville student to enroll regardless of home address.

As we begin to piece these data together, we quickly realize that access to the best schools is limited. Unless families choose to attend a high-performing charter school, students either need to live in the “right” zone, or gain acceptance to an academic magnet school.

Enrollment drain in every neighborhood

Every single MNPS cluster experiences a large student enrollment drop-off from elementary to middle school. The size of the drops ranges widely, from 40% at McGavock and Hunters Lane to 59% at Maplewood, but the trend is consistent. MNPS middle schools have far fewer students enrolled than do their feeder elementary schools.

It is an unfortunate reality that Nashville families are often forced to look outside of their neighborhood schools in order to provide their children a high-quality education. But the numbers prove that many parents are making that choice.

Nashville graduates not ready

If we track those students who do follow their zoned school pathway from the start of their K-12 career to the finish, we see the number of students classified as “On Track” or “Mastered” in English and Math proficiency slide downward from elementary school to middle school, and from middle to high school.

- Not one high school has an average ACT score of 21 (the minimum score considered college or career ready)

- Eight of the twelve high schools have average scores below 18, with five scoring 16 or below.

- At eight high schools, fewer than one in ten students are “On Track” or “Mastered” for both English and Math.

Yet MNPS graduation rates hold steady at about 80%.

Year after year, MNPS bestows upon our high school seniors a diploma, a mutually understood signal that these students are ready to forge ahead to college or the workforce. But many of them are not actually prepared for the next step.

The consequence of regularly passing students who are not grade-level proficient from one level to the next is clear: our graduates fail to meet the demands of college or the workforce. We see this plainly in college completion rates. According to a recent report by the Nashville Public Education Fund, only one in four MNPS graduates actually completes a degree after leaving the district.

A crisis in chronic absenteeism

In addition to proficiency deficits, Nashville’s high schools are also facing a chronic absenteeism crisis. A third, and in some cases more, of MNPS high school students are missing at least 18 days of school per year.

- At Stratford STEM, almost half of students miss 18 or more days of school.

- Maplewood and Whites Creek have absentee levels above 40%.

- Four more schools are at or above 30% (Antioch, Pearl Cohn, Hunters Lane, & Glencliff).

These data help to put our student achievement shortfall in context; if students are not in the classroom, our educators cannot teach them.

Bright spots of strong success

Although there are shortcomings that must be acknowledged, MNPS schools also give us reasons to be encouraged.

Each of the following schools operates within the most challenging MNPS zones— and has demonstrated remarkable achievement and growth.

- Shwab Elementary (Maplewood) is a reward school for 2018.

- Joelton (Whites Creek) shows student achievement at 40%, four times that of neighboring schools.

- Dan Mills (Stratford) presents low chronic absenteeism numbers and student achievement over 50%.

- LEAD Cameron was recognized as a Reward school for the second year in a row. This school serves as the zoned middle school option for students in the Glencliff cluster.

It is true that data only tell one side of the story, and that the context for these numbers can vary widely from school to school, classroom to classroom. But by diving into these numbers, we are able to illuminate the parts of our public school system that are working well, and to put a critical spotlight on the areas that desperately need improvement. With this goal in mind, we will continue to highlight our top data-driven takeaways in a series of blog posts to be released over the coming weeks.

We hope to present school data in a way that feels accessible to all members of our community, from parents to principals, employees to CEOs. We believe that when all Nashvillians can have an informed conversation about our public education system, innovation and improvements will follow. Together, we can take steps to ensure that every child in Nashville receives a high-quality public education and is prepared for success after graduation.

Please check back for more on our blog series on the MNPS Cluster Profiles.

Tags: MNPS Cluster Profiles

Inner circle: Here’s who education chief Penny Schwinn will lean on in Tennessee

Less than three months into the job, Tennessee Education Commissioner Penny Schwinn has filled six of her nine cabinet positions with a mix of new hires, retentions, and promotions as she begins to restructure one of the state’s highest-profile departments.

Schwinn, who took the helm of the 600-employee education department in early February, said she wants to have her entire team of top advisers in place by July 1, the start of a new fiscal and school year.

For her chief of staff, Schwinn has picked Rebecca Shah, who worked at the Texas Education Agency where Schwinn served as deputy commissioner of academics before Gov. Bill Lee hired her to be Tennessee education chief.

“She ran performance management for me in Texas, so she really knows what I’m looking for in terms of data collection and holding us internally accountable,” Schwinn said of Shah.

Her deputy commissioner will be Amity Schuyler, soon departing as the superintendent’s chief of staff in Palm Beach County, Florida, the nation’s 10th largest school district.

Schwinn is still hunting for a chief district officer and an assistant commissioner of communications and engagement. But atop her list of vacancies to fill is chief academic officer.

“I am picky,” Schwinn said of that role, “because that’s when you think about what goes in front of our kids every day, and the instructional materials that they use, and the teacher in front of them. The chief academic officer is really leading in terms of executing that vision.”

The jobs are among a dozen high-level openings listed on the state’s website, including assistant commissioner of school improvement.

Sharon Griffin, hired last year to run the state’s highest-profile school turnaround program, will keep that role at the Achievement School District, Schwinn told Chalkbeat this week. However, under a revised chain of command, Griffin will report directly to a new chief schools officer instead of to the commissioner, as she had under Candice McQueen, Schwinn’s predecessor.

While reorganizing is common for a new commissioner, Schwinn’s hires thus far show she is leaning on some experience and institutional knowledge from within Tennessee’s education department while also recruiting a few key outsiders.

Retained from McQueen’s cabinet are Christy Ballard, the department’s general counsel, and Assistant Commissioner Elizabeth Fiveash, who oversees legislative affairs and policy and maintains a daily presence on Capitol Hill when the General Assembly is in session.

Promoted from within are Eve Carney, who as chief schools officer will oversee school improvement initiatives including the Achievement School District; and Sam Pearcy, who as chief operating officer will look after finance, information technology, procurement, and school services.

Carney joined the department in 2008 and previously administered federal grants programs. Pearcy, who has been with the department since 2013, has focused most recently on improving state efficiency to support school districts.

Schwinn said her new organizational chart, which is slated to go into effect on May 1, was developed with feedback from district superintendents.

The restructuring shrinks the commissioner’s cabinet-level advisers from 11 to nine and also scales down the number of people reporting directly to Schwinn. Below is the organizational chart from last fall, before the change in administrations.

The arrivals under Schwinn coincide with some high-level departures.

McQueen’s chief of staff, Laura Encalade, left along with former communications director Sara Gast to work for their former boss in McQueen’s new role as CEO of the National Institute for Excellence in Teaching, a nonprofit organization focused on attracting, developing, and keeping high-quality educators.

Chief Financial Officer Chis Foley was dismissed by Schwinn.

Others, like former deputy commissioner Kathleen Airhart and former chief academic officer Vicki Kirk, accepted other jobs before the change in administrations.

Lyle Ailshie, who as deputy commissioner stepped in as the department’s interim leader before Schwinn started, is expected to retire mid-year and return to East Tennessee, where the state’s 2005 Superintendent of the Year oversaw districts in Kingsport and Greeneville.

Meanwhile, Schwinn has moved her family to Tennessee after commuting on weekends to Austin during her first months on the job. The oldest of her two daughters is a student in Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools.

[Read more at Chalkbeat] Read More